Over a month ago, an architecturally interesting home was listed on the market for the first time in almost twenty-five years, a property I’ve long intended to write about in my never-ending series on architects’ own residences located across Chicagoland. Many renowned architects called the Gold Coast home over the course of Chicago’s history: John Wellborn Root, Bertrand Goldberg, Benjamin Marshall, David Adler, Andrew Rebori, and even Frank Lloyd Wright for a brief period. James F. Eppenstein may not be a household name, but his home truly stands out. Tourists are often surprised to learn that the structure is older than it appears. You’d be surprised too.

Right across the street from where Governor Prizker resides is one of Astor Street’s more unusual designs. A rare example of an International Style residence in Chicago, it caused quite a stir in architecture circles after it was featured in local and national publications. However, before Eppenstein’s remodeling in 1938 (the same year Mies van der Rohe moved to Chicago), the building began its life as a Romanesque Revival-style townhouse, originally owned by Bernard E. Sunny. According to the Chicago Inter Ocean, the building permit for the home was issued in May of 1889 to E.B. Sweeny, most likely a developer, as there is no evidence he ever lived here. The three-story dwelling cost $8,000 (almost $274,000 today) to construct. On FamilySearch I confirmed that Sunny was the original occupant as the address at that time (138 Astor Street) is listed on his October 1889 voter registration card, which also provides some evidence of when the home was officially completed.

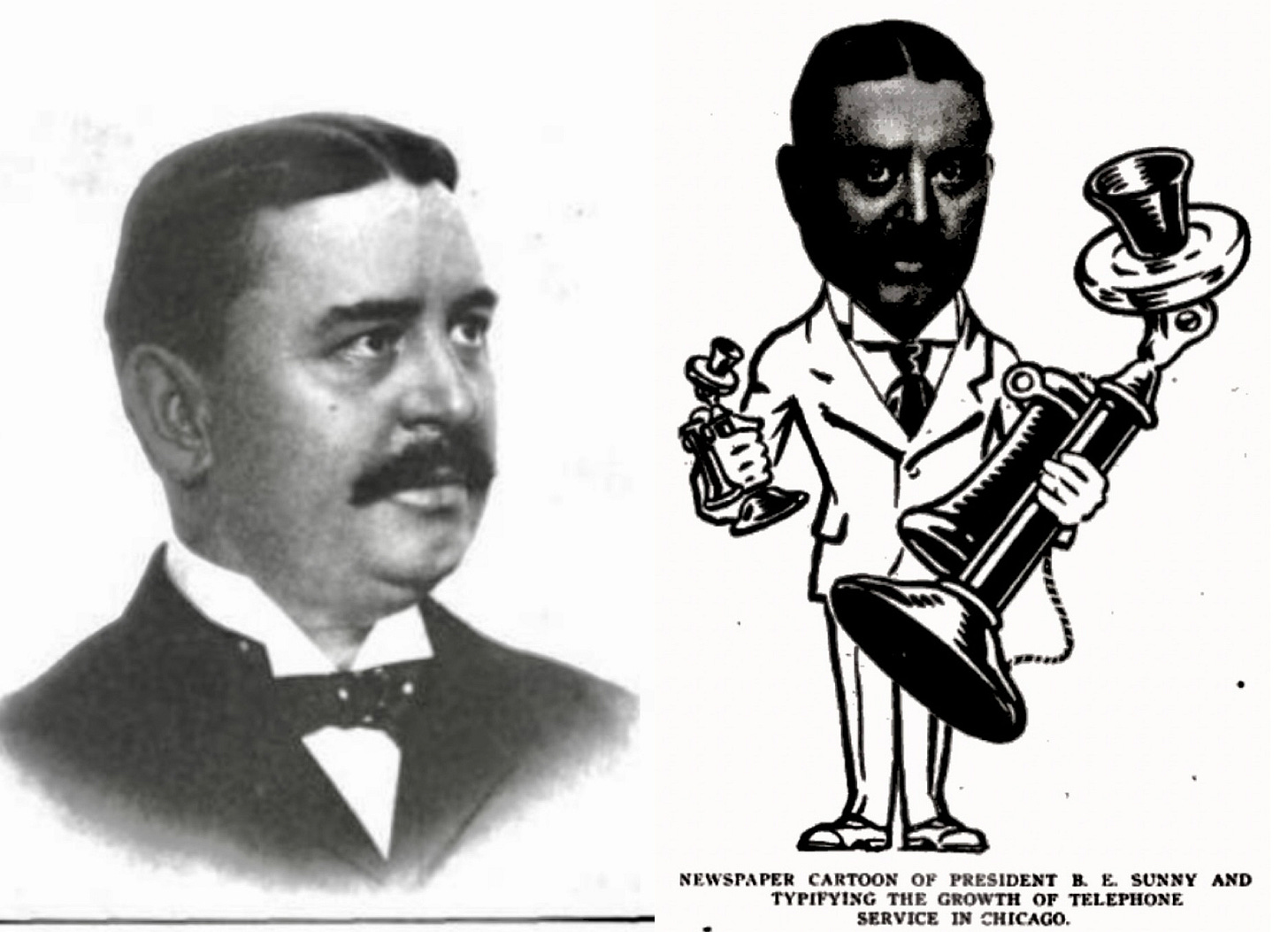

One of the most powerful and wealthiest men in the city, Sunny joined the Thomson-Houston Company in 1889, and later became the vice president of its successor, General Electric. He served as President of the Chicago Telephone Company, a predecessor to Illinois Bell. The Sunnys lived on Astor for approximately twenty years. Unlike their neighbors who had up to ten live-in help, the family had only a German cook and another servant listed on the 1900 census. They socialized often, especially when the 1893 World’s Fair took place, and summered in a cottage on Fox Lake.

By 1910, Bernard Sunny, his wife Ellen Rhue, and their two children, along with three servants (a cook, a maid, and a janitor) were residing at 4933 Woodlawn Avenue in Chicago’s Kenwood neighborhood. Six years earlier, in 1904, Sunny built this new residence, commissioning architect George Beaumont, who had designed a row of frame concession buildings on 57th Street for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (these structures survived until the 1960s when they fell victim to urban renewal). Sunny had negotiated with the Chicago Beach Hotel for their water rights, which allowed South Lake Shore Drive to be constructed along the lakefront.

According to his death certificate, Sunny died of hypertension on October 5th, 1943 at the age of 87. For the past twenty years, he’d been living with his second wife, Emma Holmes, who passed away five years after him, at 4913 Kimbark Avenue. It was just a block over from his previous home and was designed by Holabird & Roche. While hard to believe today, cows grazed on a a ten-acre pasture directly behind it. In October of 1922, just after the colonial revival home’s completion, then unoccupied, labor activists threw a bomb. Its explosion rattled and broke windows of Sunny’s home as well as neighbor Jacob M. Loeb (we’ll get to his family in a minute). Sunny was a major donor to the University of Chicago, serving as chairman of several development committees, and the school’s gymnasium is named after him.

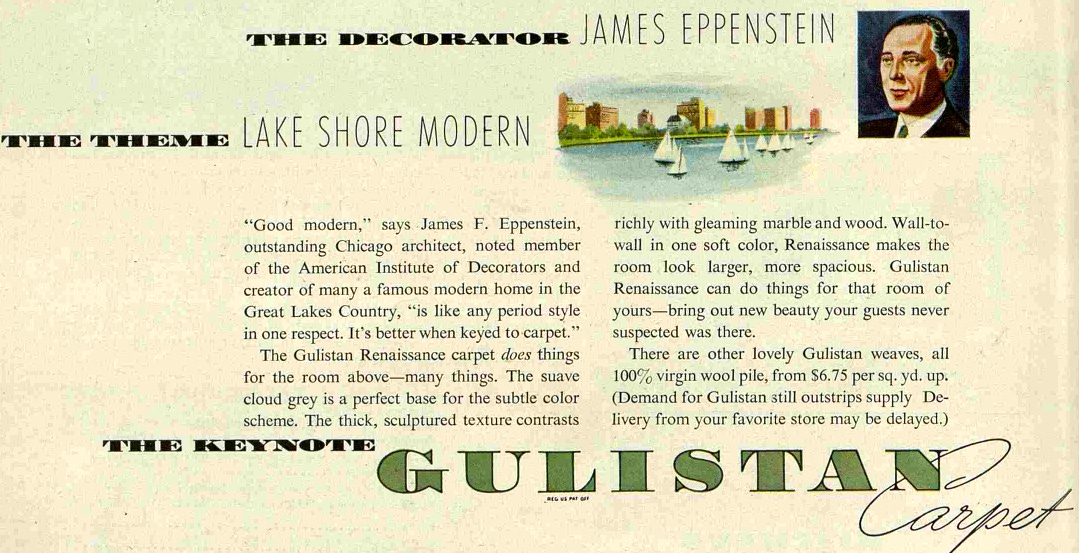

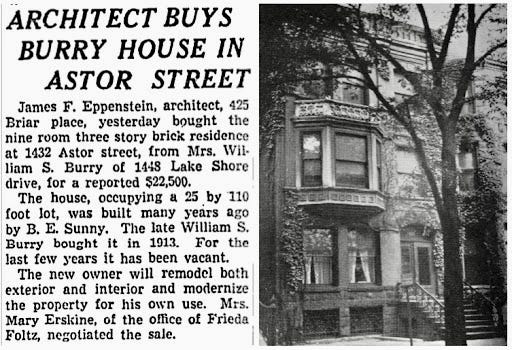

Let’s return to the Astor Street home. Based on my research of census records and newspaper articles, it appears that there were at least two owners between Sunny and Eppenstein. The first was Frederick Belcher Smith, a retired capitalist who made his money through the A.C. McClurg Company and belonged to the Union League and Chicago Literary Clubs. In May of 1913, Smith sold the property to Mr. and Mrs. William Burry. By the time Eppenstein acquired it from them for $22,500 (or almost $500,000 today) in 1938, the property had been vacant for several years. He had immediate plans to modernize the home, both inside and out, but who was this man?

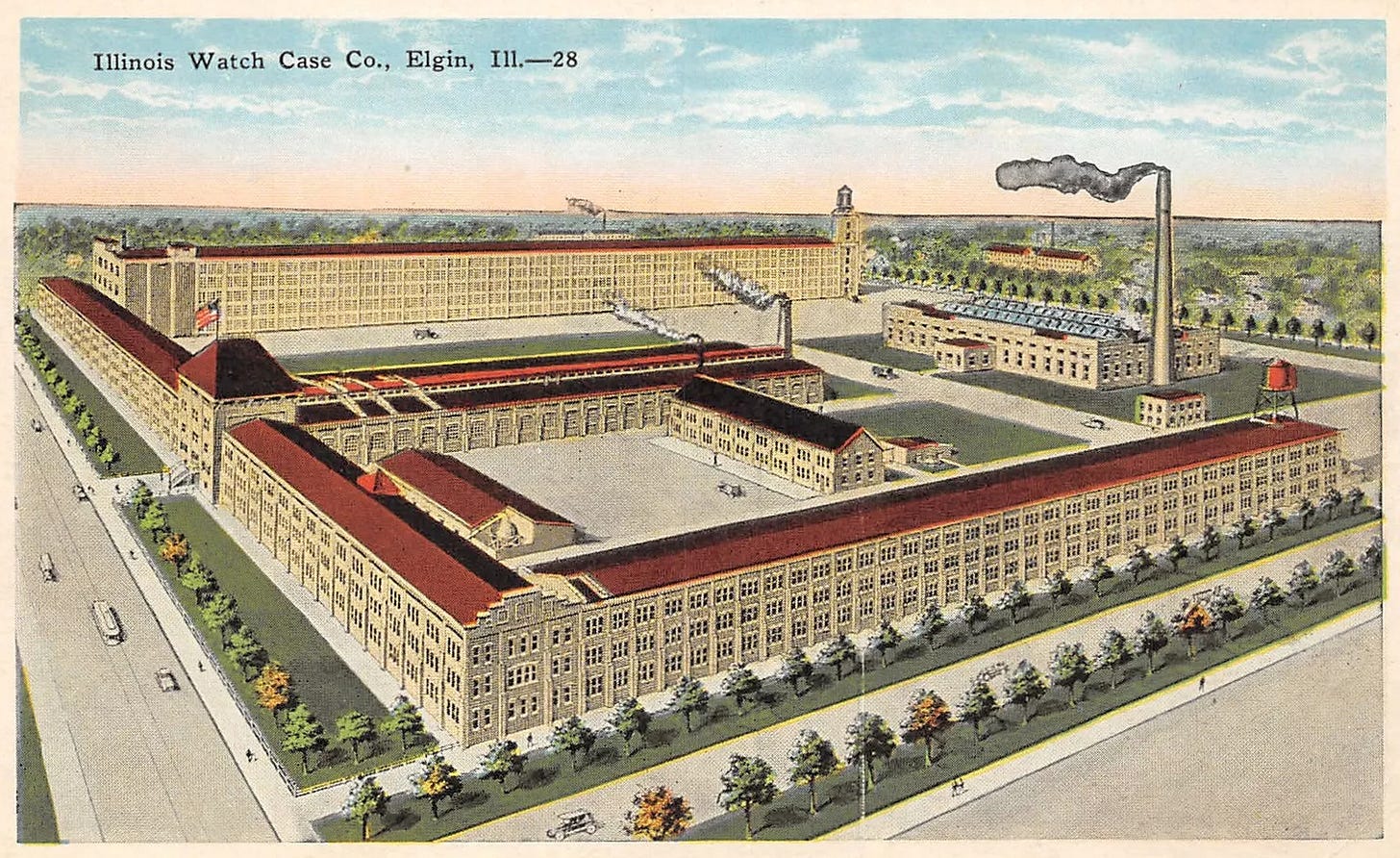

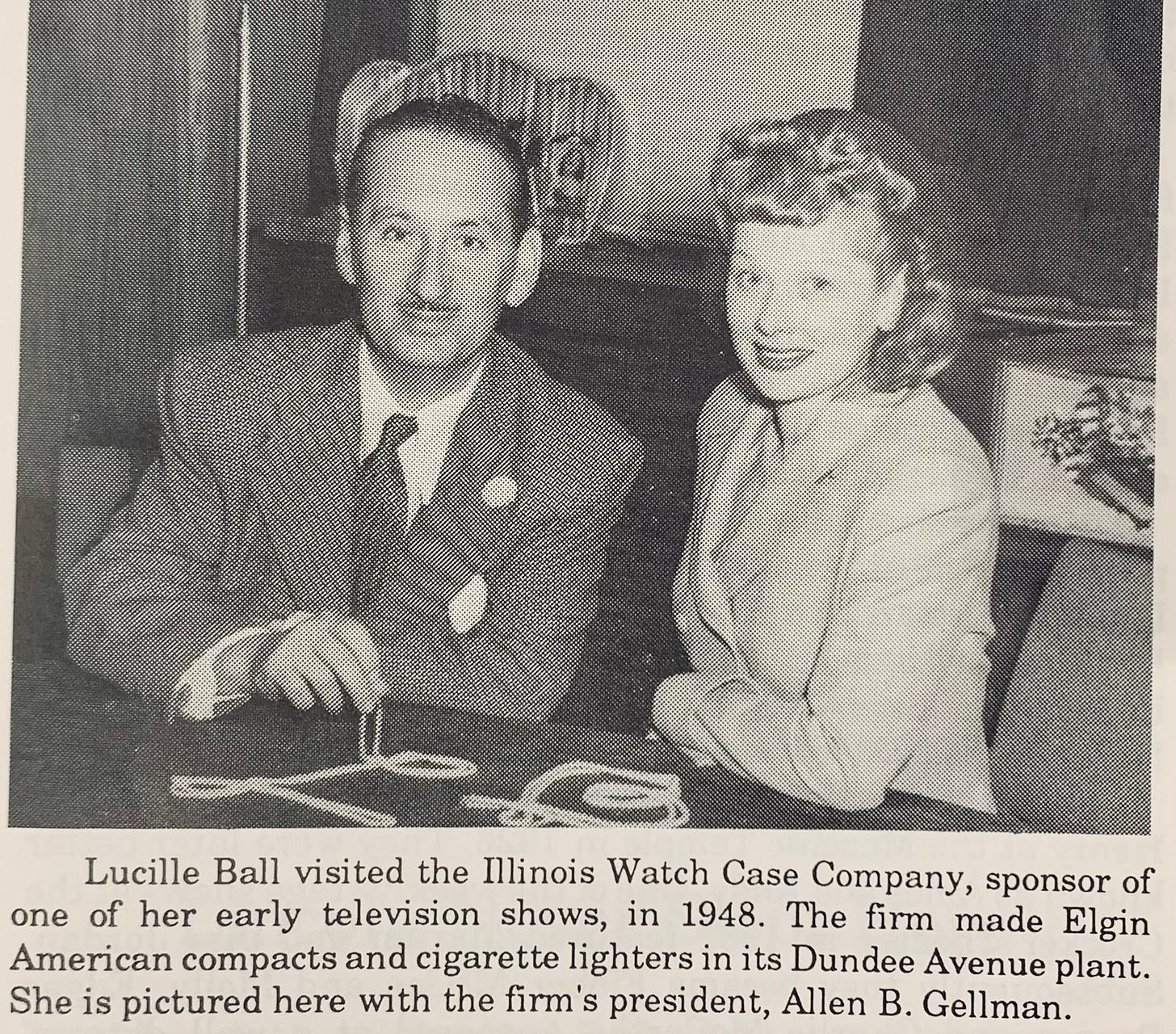

If you’re wondering how a young architect, just starting his career, could afford such an expensive home along with renovations, it’s important to note that James Eppenstein grew up in one of the wealthiest families in the area. In 1880, his father, Solomon or “Sol,” arrived in Chicago and six years later co-founded the Illinois Watch Case Company. Due to the popularity of the Elgin National Watch Company, Sol’s plant moved to Elgin, where James Eppenstein was born in 1899. The company was the city’s second largest employer, though products made in Elgin were found all over the world during this time: watches, shoes, canned food, condensed milk, and Bibles.

Although he spent most of his childhood living in a home on Liberty Street, as a teenager, his father built a grand brick home on the city’s most fashionable street. Neighbors included the Bordens. Located at 940 Douglas Avenue in what is now Elgin’s Spring-Douglas Historic District, the design, blending Prairie School and Mediterranean Revival influences, was created by architect George E. Morris and completed in 1917. In today’s money, it had cost almost $1 million, which shows the level of wealth and privilege Eppenstein grew up with. When his sister, Helen-Aimee, married in 1924, an entire floor of Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel was taken over by the ceremony and hundreds of guests, which included Irving Florsheim.

Sol was vice-president of the company when his son graduated with high honors from Cornell University in 1919. It was expected James would join the family business, which he did, working as general manager of its subsidiary, Elgin American, a manufacturer of vanity cases, cigarette cases, lighters, lockets, and other small jewelry items. According to Art Deco Chicago, James had traveled to France in the 1920s and might have served as the catalyst for the 400 modernistic Art Deco designs produced by the company between 1929-32. But architecture came calling in 1928 so he might have just lit the spark at his father’s company. Who knows? He went on to attend the University of Michigan, the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and received a Masters degree from Harvard University in 1933. James also studied furniture design at Hochschule für Frei and Angewandte Kunst in Berlin.

Sadly, his brother Sidney, who was meant to take over the family business died in an auto accident at the age of 20 in 1929. He’d been traveling in Ripon, Wisconsin with his father when the “stering knuckle” of the car broke, which caused them to crash into a tree. Sidney suffered a skull fracture, a broken arm/right leg, along with internal injuries. Probably due to this tragic event, two years later, Sol sold his interest in the company to nephew Louis Eppenstein, and retired to the Belmont Hotel at 3156 Sheridan Road (here is a historic image of the building). He died in 1938. His former company, which produced 900 cases a day at its peak, ceased operations in 1963.

But what is probably the most interesting thing about James’ family background (and this is my true crime obsession coming through) is his connection to the Leopold and Loeb case. James’ mother, Rebecca “Beckie” Franks Eppenstein, was the sister of Jacob Franks, making James the first cousin of Bobby Franks, the victim of “The Crime of the Century.” When Beckie, the daughter of a millionaire, married Sol in 1898, the local press described it as “one of the most brilliant of this year’s Jewish weddings.” Sol owned and operated the Rockford Watch Company with his brother-in-law (and Bobby’s father) Jacob Franks from 1901 until 1916. After Jacob’s death in April of 1928, James, whose middle name was Franks, became a trustee of his uncle’s estate, helping to decide how best to use the $100,000 set aside for a Robert Franks memorial. A new clubhouse for lower-income boys was established at 3415 W. 13th Place in Chicago’s Lawndale, which is still in use today.

So let’s *finally* talk about the personal residence of architect James F. Eppenstein, who remodeled B.E. Sunny’s 19th century Romanesque townhouse into a modernist dwelling in 1938. As described in the August 1939 issue of House & Garden, he couldn’t resist “rejuvenating the respectable though stolidly dull brick front with its jutting bay window and florid copper ornamentation,” then 50 years old. The facade was covered in granite, completely erasing its past. The front stoop was taken out and he moved the entrance to the basement level, which was accessed by a new modern staircase with stainless steel handrails. The base, made of dark red granite, matched the trim, which was painted in the same color to create a cohesive look.

He might’ve gotten the idea from prominent Chicago artist Edgar Miller, who had been converting older buildings into modern studio complexes since the 1920s. As far as I know, Eppenstein and Miller’s work coincided on at least two projects: an interior at Fisher Studios, not far from his own home, and the chic lounge inside the now shuttered Standard Club, which had an intricately carved mural of black linoleum that depicted “The Great Chicago Fire.” Eppenstein was also probably been influenced by Mies even before the famous Bauhaus architect moved to Chicago as he had studied in Berlin in the early 1930s. It is obvious in the home’s design of space and structure.

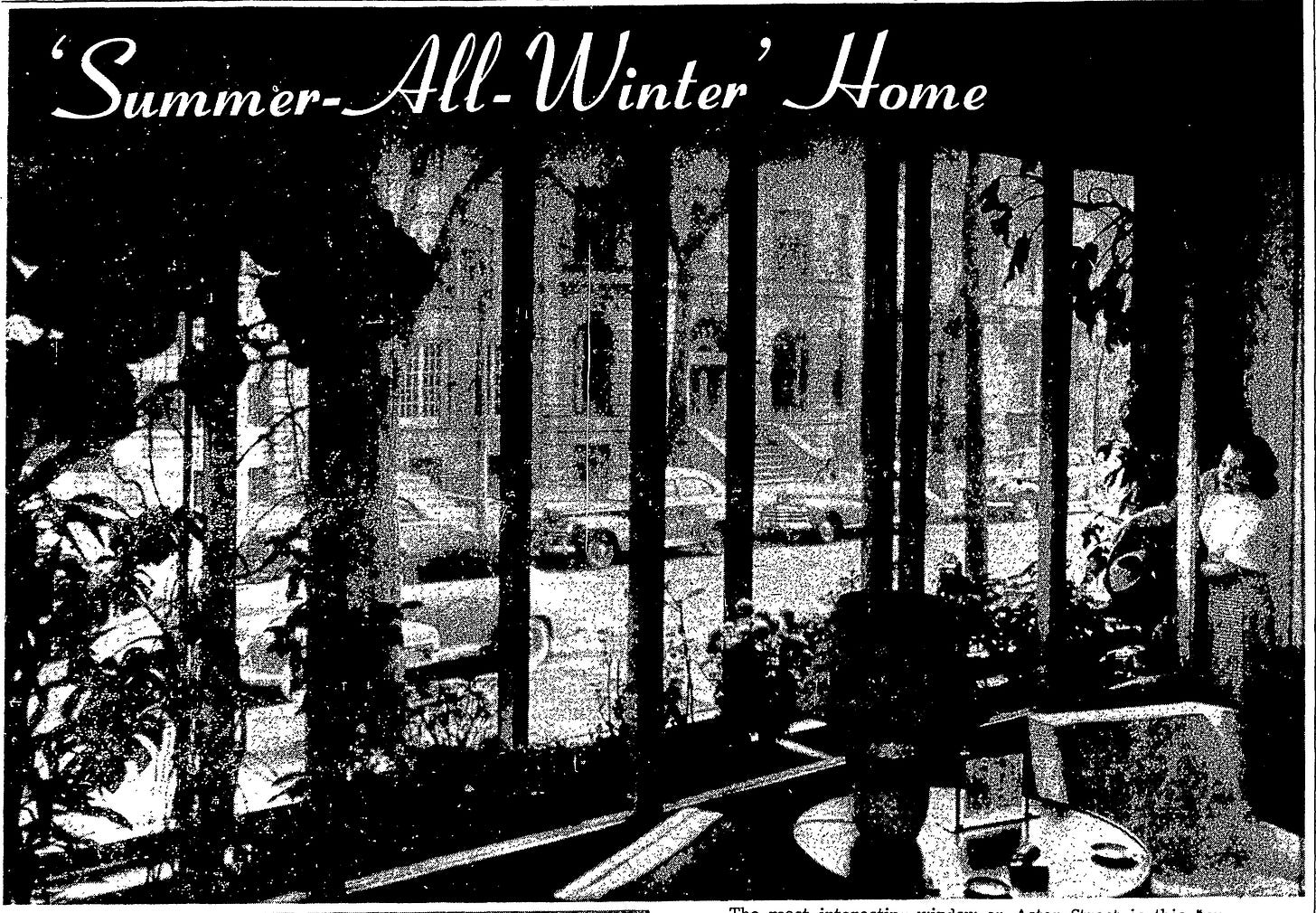

Inside sheer draperies and indirect fluorescent lights created dramatic spaces while plant boxes were located under the large windows. The colorful decor included dark green handmade tiles in the entryway and various rooms were accented with navy blue and turquoise. Eppenstein created built-ins made of birds-eye maple, custom-designed walnut pieces for the living room, and a wooden handrail on the decorative staircase. On the walls of their newly remodeled home, modern art was on display, including “Landscape with Church” by Kandinsky that was later sold by the family for $2.4 million in 1987. Their outdoor space included a limestone piece by sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson called “Summer” that was part of her “Four Seasons” collection.

James lived here with his wife Louise, an author of children’s books, and their two daughters, Sally and Peggy. They had married in Chicago in June of 1925. According to the 1940 census, the family employed a maid, Katherine Conroy, and a cook, Nora Burke, both of whom were originally from Ireland and resided with them. When the Eppenstein residence was completed, it caused quite a stir in the architecture world. It was published not only locally but nationally as well, including the Architectural Forum. In March of 1939, the couple even won a $1000 prize from General Electric’s national “new American home building” contest (one of the other winners that same year was architect Philip Will). As you will soon see, Eppenstein’s design for his own home was reflected in some of his other projects.

He established his own firm in 1934 and later partnered with Ray Schwab, who had studied alongside Robert Bruce Tague at the Armour Institute in the mid-1930s. In an interview with Betty Blum, Tague recalled how the two “did a lot of interiors” and that “maybe the best thing they ever did” was Eppenstein’s own home on Astor. Their office was first located at 646 N. Michigan Ave (now the Starbucks Reserve Roastery), then they moved to 35 East Wacker Drive. The December 1935 issue of American Architect featured an article describing his office as “furnished in the modern manner” with walls covered in a mahogany veneer and matching furniture and light fixtures. The ceiling and flooring were copper while the couch was made of green leather.

The firm found it more profitable to modernize commercial structures than design their own, so they specialized in revamping offices, showrooms (mainly at the Merchandise Mart), restaurants, and large hotels. Besides doing murals like the one located inside the WGN Broadcasting Studios Building, Eppenstein also created furniture, which were executed by the Garland Furniture Company and came with an attached label that read “Designed by James F. Eppenstein, Chicago.” He was probably inspired by other modernist furniture and interior designers working in Chicago, like Philip B. Maher, John Wellborn Root Jr., Abel Faidy, George Fred Keck, and Samuel A. Marx. In 1927, the city’s first modern decorative arts shop, Secession Ltd., had been established by architect and furniture designer Robert Switzer and Harold O. Warner, resident architect of the Art Institute of Chicago. Its location at 1008 North Dearborn, not far from Eppenstein’s own home, had to serve as another inspiration.

In total, Eppenstein completed about 76 building projects. Besides major hotel remodelings, probably his most interesting design was a fast train called the Electroliner for the North Shore Line Railroad. One of his passive solar homes was featured in a promotional booklet. Besides his work as an architect and interior designer, he also wrote an advice column “What’s Your Decorating Problem?” for the Chicago Tribune and he also had at least ten different patents for various types of furniture, such as a cantilevered ashtray and a convertible sofa bed. After reading through vintage architectural journals and magazines, I noticed one of his signatures as an interior designer was to conceal a bar or opening behind a sliding door that blended seamlessly into the paneling.

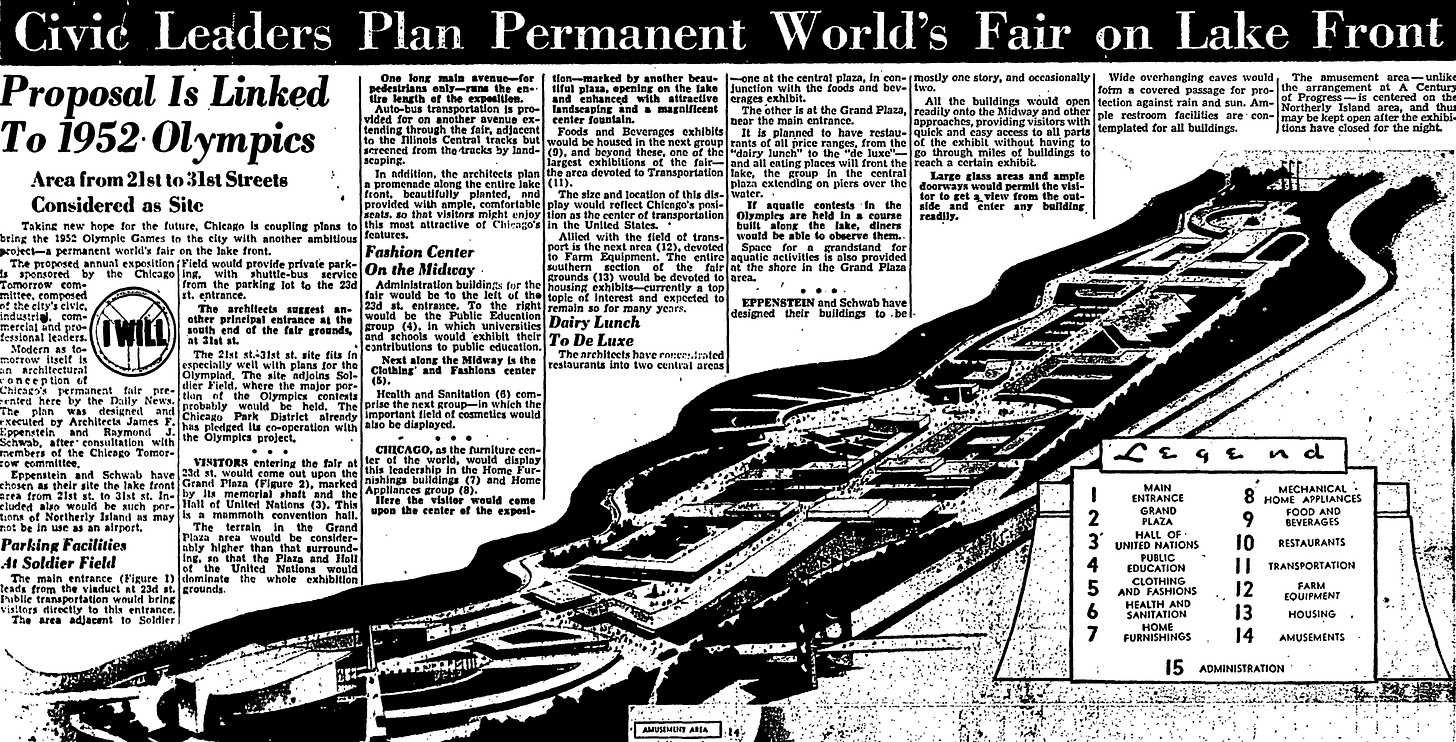

In 1947, the firm designed and executed a plan for a permanent world’s fair on the lakefront as the city was hoping to host the 1952 Olympics. In consultation with the Chicago Tomorrow committee, the site was to be located between 21st and 31st streets with two main entrances and restaurants located in central areas with eating areas near piers that would extend into the water. Amusements and other attractions would be kept on Northerly Island. But it wasn’t meant to be.

In 1952, a block over from his house, he took on a remodeling project with the historic 18-room Gurley mansion at 1416 N. State Parkway, which was converted into a”de-luxe five-flat.” He also worked on an interior for Mrs. Robert Altman in the new 1350 North Lake Shore building. That same year, after his daughters moved out, he remodeled his own four-level home into three separate apartments, adding a door and exterior staircase to the building. James and Louise lived right above the basement level. Fortunately, the changes were removed and the facade was restored when it was later converted back into a single-family home, which won a Chicago Landmark Award for Preservation Excellence in 2000-01.

Although a contributing property to the Astor Street Historic District, Eppenstein’s rare International Style home is not individually landmarked, raising significant concerns about its future, especially now that it is for sale. While I do not believe it would be demolished, this unique modern building deserves official recognition and protection. With the exception of a historic edition of Chicago on Foot, the home has never been featured in local guidebooks. It is unfortunate that Eppenstein is largely forgotten today, which is partly due to the fact that his career lasted only about twenty years and primarily focused on interiors. He passed away in June of 1955 after suffering a series of strokes. Even with his overall prominence, I could only find a brief obituary in the Chicago Sun-Times and not the Chicago Tribune, although he had a column in that newspaper.

In the years leading up to his death, the family endured a couple of unfortunate incidents. In August 1950, a thief stole jewelry and family heirlooms from their home on Astor Street with a total value over $3,000 (around $41,400 in today’s money). Two years later, in July 1952, Eppenstein was involved in a so-called “freak traffic accident.” His speeding car on Route 12 near Long Beach, Indiana, collided with another car, resulting in a young passenger’s arm being thrust through a vent window. It reminds me of the car crash that took his brother’s life thirteen years earlier. According to a news article, Louise Eppenstein, then 67 years old and still residing in the Astor house, had her own brush with death. She was one of the victims injured and hospitalized after an explosion leveled a block of stores on Van Buren between Federal and Dearborn at the end of July 1968. She passed away in July 1987.

Besides his own home, what survives of Eppenstein’s work? Well, in Chicago not a whole lot, though this series by Forgotten Chicago, published in 2013-14, goes into great detail of what he exactly did. He “copied” the Astor Street home in a later commission from 1948, the surviving Leterstone Sales Company at 2511 S. Wabash (now painted black), next to the Stevenson Expressway, just south of Motor Row. Patrick Steffes speculates that the apartment Eppenstein designed for client David Rostenthal in 1938 was in the building at the corner of Spaulding and Potomac, which has glass blocks with limestone directly underneath on its exterior.

In the North Shore suburb of Highland Park, Eppenstein designed seven single-family residences, although at least two have since been demolished. One of his most innovative designs was an International-Style home with Art Deco influences built for Dr. Gustave and Rosalie Strauss Weinfeld in 1935. Its flat roof, band of windows, vertical strip of glass blocks, and minimal ornamentation must have been shocking at the time. The original owners were progressive in their own right, as Dr. Weinfeld was one of the first pediatricians in the area, while Rosalie served as the director of the Ravinia Nursery School. Although the home now features an addition (a grey box covers what used to be a terrace) above the garage, it could have met the same fate as other Eppenstein designs. So I am more than pleased that this modernist residence at 401 Woodland Road still stands. (Don’t forget, this is the North Shore, where they like demolishing the past!) Nearly twenty years later, Robert S. Adler commissioned Eppenstein to design a ranch that surprisingly still exists at 1446 Waverly Road. There is also another International Style design by him from 1941 that survives at 214 Cedar Avenue. It has a limestone base, one of Eppenstein’s signature touches. None of his work here has been designated individually as a landmark, nor is any of it included in a local historic district. This is a shame. Eppenstein deserves to be remembered as an important modernist who contributed to the Chicagoland’s built environment.

SOURCES:

“Sharply Defined Masses: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein” in three parts by Patrick Steffes

http://undereverytombstone.blogspot.com/2015/06/be-sunny-bernard-e-sunny.html

USModernist - Architecture Magazine Library

Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975 by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino

Chicago’s Historic Hyde Park by Susan O’Connor Davis

Chicago Furniture: Art, Craft, and Industry, 1883-1983 by Sharon Darling

Art Deco Chicago: Designing Modern America edited by Robert Bruegmann

Do you have a list of the 7 Highland Park homes and addresses? I'm quite interested in this architect. Thanks, I love your writing and research on so many great architects.

Thank you for sharing this. The photographs were helpful to get a clearer understanding of the range of his work, especially those lovely interiors and pieces of furniture.

Kind of a gruesome description in the newspaper article about the boy who got his arm snapped off.