Architect Homes: Bertrand Goldberg

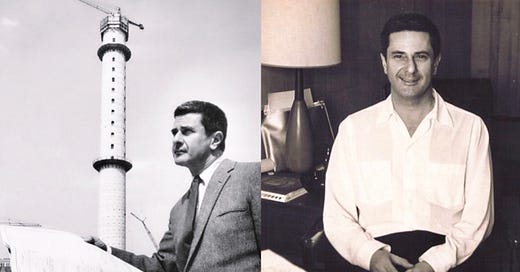

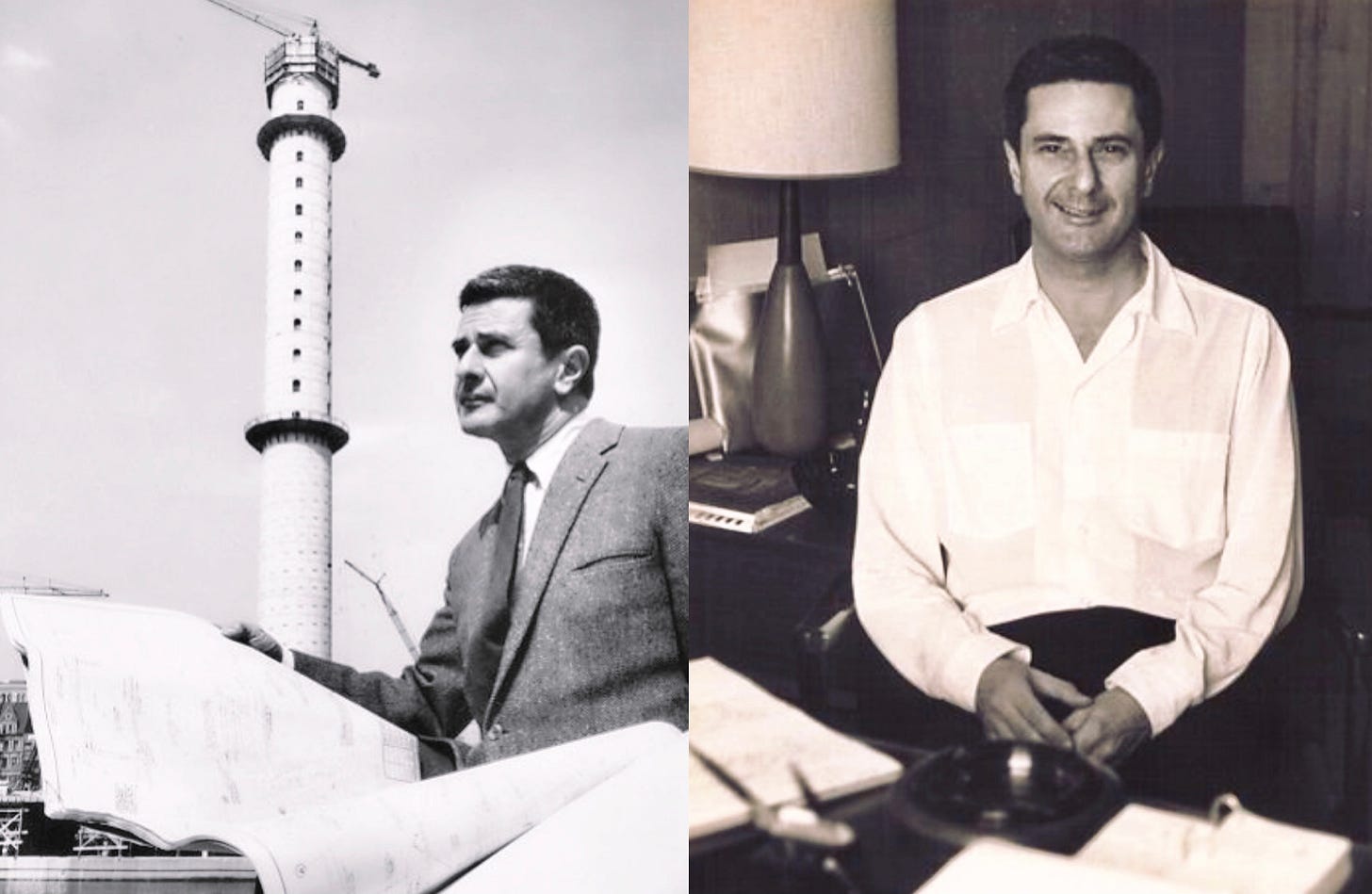

Unlike other architects I’ve featured throughout this series, Bertrand “Bud” Goldberg (1913-1997) did not design his own home. Best known for the Marina City complex and the now-demolished Prentice Hospital, Goldberg had experience with residential work going all the way back to his first commission in 1934 when he created a prefabricated canvas-covered house for feminist Harriet Higginson. While still in his twenties, Goldberg continued to design single-family houses for people like magazine editor Thomas H. Mullen in Evanston in 1936 as well as advertiser Nathan Jacobs in Glencoe in 1941. Dr. Aaron Heimbach commissioned the young architect to plan a home in Blue Island in 1939, its dual function as a residence and medical office makes it a rare example of a mixed-use structure, while the Chicago common brick exterior with massive vertical chimney gives the design “a distinctly urban quality.”1

Bud Goldberg grew up in the Kenwood neighborhood, attending both the Harvard School for Boys and the Chicago Lab School. At age eighteen Goldberg went to Germany to study at the Bauhaus and briefly worked as an intern in the office of legendary Mies van der Rohe. While a big proponent of Mies’ design principles, which is apparent in the Heimbach House done in the International Style, Goldberg overall defied architectural labels after he started his own architectural practice in 1937. One can see that in Goldberg’s experimental nature, which resulted in a variety of designs throughout his career from a midcentury modern ranch in suburban Flossmoor to the curving forms of River City and the Elgin State Hospital.

When Goldberg returned to Chicago, he briefly lived at the rear of the Farwell House as discussed in a three-part series on “Tower Town” by Forgotten Chicago. Goldberg recalled his post-Germany life in the 1930s: “In those years I lived on Michigan Avenue and Pearson Street. There was a very big old stable and garage there at the northwest corner of Michigan and Pearson, adjacent to Tower Court (now known as North Michigan Ave). It was a commune, really, as we have some to identify them, but I think about forty or fifty people lived in that building, very inexpensively, and I shared a studio with (artist) Edward Millman.”2 While living in this “commune” Goldberg got to meet other local artists like Edgar Miller and Richard Florsheim, a cousin of his future wife. It’s not known how long Goldberg lived in the rear building on Pearson but during this time he was designing small residences as a struggling, independent architect (ironically Goldberg would later design a beauty salon inside the 840 Michigan Ave building on the same block as his former home).

Goldberg’s early residential commissions received little attention at the time they were built and are “an oft-overlooked aspect of his career.”3 Yet with all these dwellings under his belt, it’s somewhat surprising that Goldberg didn’t end up creating a house for his own family. I would assume it was because he lived in Chicago’s Gold Coast for the majority of his life, a neighborhood where a number of architects resided through the 19th and 20th centuries: David Adler, Andrew Rebori, Benjamin Marshall, Frank Lloyd Wright, and John Wellborn Root, who I wrote about in an earlier article. When Root designed a group of townhouses at 1308-12 Astor Street in 1887, the area was just taking off again fifteen years after the Great Chicago Fire destroyed it. When Goldberg moved here in the 1950s, times had changed. Vacant land was unavailable to build a single-family home from scratch so instead a historic home was chosen.

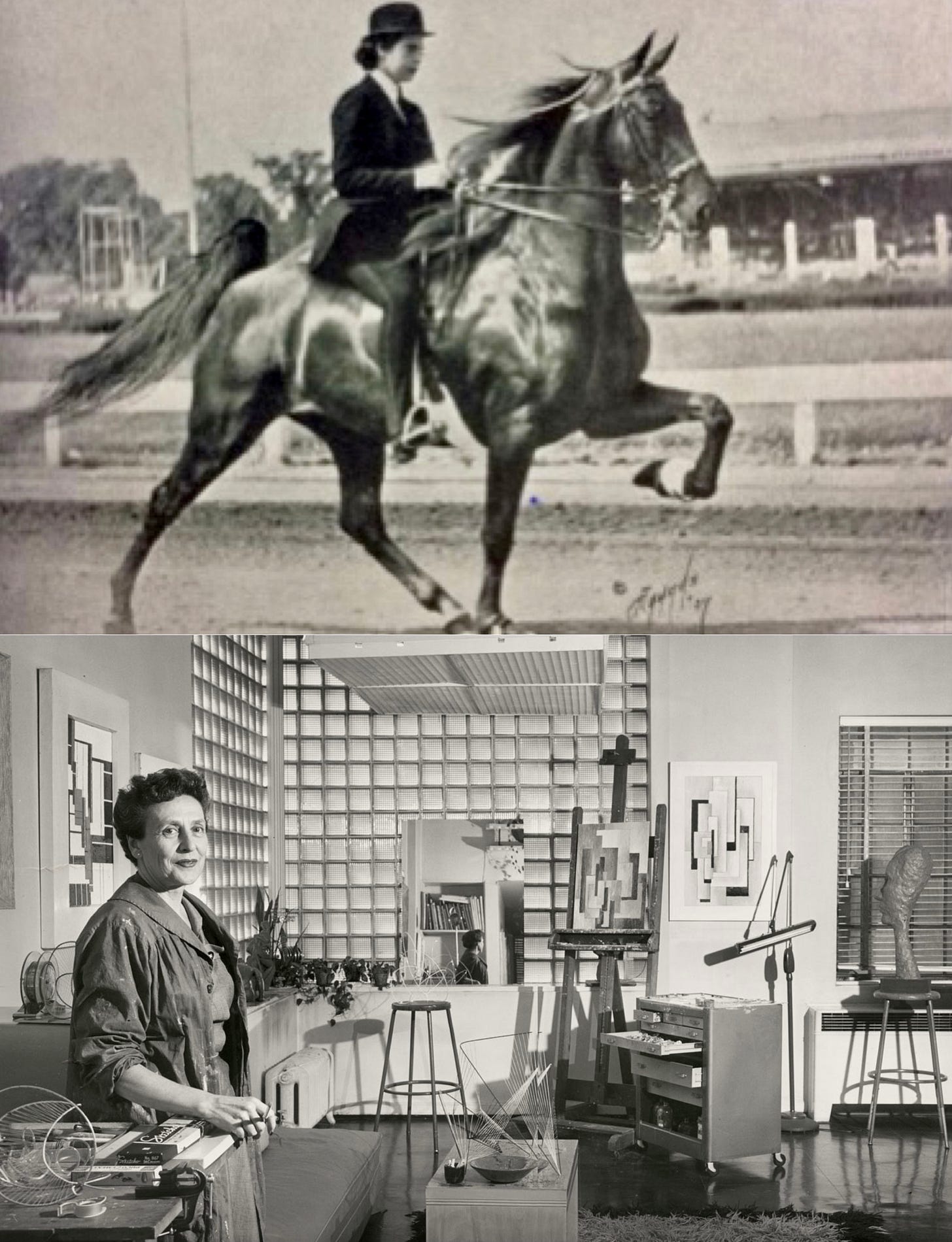

The Francis R. Dickinson House at 1518 N. Astor St was produced by the architectural firm of Jenney, Mundie & Jensen in 1911 (the architect Elmer Jensen will be discussed in a future article of this series) in the then popular Georgian Revival style. That same year the architects also created a similar-looking building right across the street next another red brick Georgian mansion done by Richard L. Schmidt. The Dickinsons sold their 20-room home in 1940 to the Walter Meads for $50,000. By 1954 it was then sold to Nancy Florsheim, daughter of Irving Florsheim of the Chicago-based Florsheim Shoe Company. She had bought it for $65,000 (or nearly $680,000 with inflation). Eight years earlier Nancy had married Bertrand “Bud” Goldberg, who had not yet designed some of his most famous buildings, but was now living in a neighborhood full of money and social connections.

Before their marriage in 1946, Nancy was living with her mother Lillian at 1328 N. State Parkway after her parents’ divorce. Irving and Lillian Florsheim had lived at Red Top Farm in Libertyville, which they had purchased from the Insull family. Lillian had not been happy with the traditional ways of her husband; this new home allowed her freedom to practice and display abstract and avant-garde art. Nancy and Bud’s wedding ceremony took place on the first floor of the Florsheim home, which was actually two separate buildings on opposite ends of a narrow city lot with a courtyard in the middle. The Art Moderne design of brick and glass blocks was originally built by its first owner, architect Andrew Rebori, in 1938. Each structure has its main living space on the second level. Just a year after his marriage to Nancy Florsheim, Lillian’s new son-in-law Bug Goldberg connected the main living quarters with the rear coach house via a narrow “skybridge” kitchen. The floor is suspended from metal rods (in tension) and enclosed with a fiberglass screen, which is meant to mimic the sleek lines of streamlined railroad car kitchens. Both Lillian and Bud were interested in geometry, having “a lot of conversations about specific shapes of curves,” so it makes sense they worked on this project together.4 Just before Lillian Florsheim’s death at the age of 92 in December of 1988, Bud and Nancy Goldberg moved into her residence.

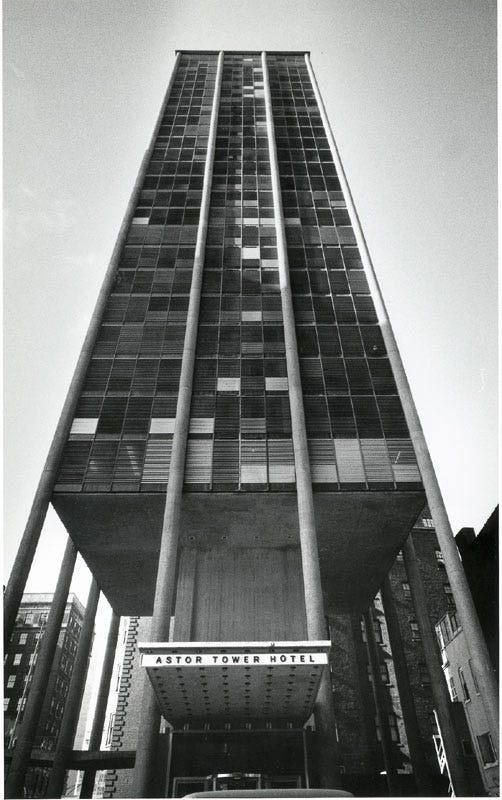

A few blocks away from both his mother-in-law’s home as well as his own, Goldberg designed and built what became the Astor Tower Hotel the NW corner of Astor and Goethe between 1958-63. Although it was constructed at the same time as Marina City, Astor Tower is better known as the site (specifically the 27th floor) where John Lennon apologized for suggesting “The Beatles were more popular than Jesus” than its ground-breaking modernist architecture. At that August 1966 press conference, John attempted to defend himself: “I wasn’t knocking it or putting it down. I was just saying it as a fact . . . I’m not saying that we’re better, or greater or comparing us with Jesus Christ as a person or God as a thing or whatever it is, you know. I just said what I said and it was wrong, or was taken wrong. And now it’s all this.”

The hotel was Goldberg’s first major project to show his experimentation with poured concrete structural forms as well as his lifelong obsession with prefabrication. The concrete core, poured in place over a three-week period, carries much of the bulk of the building, therefore all twenty-four floors are cantilevered off it.5 As described in the AIA Guide to Chicago, “the concrete columns raise the lowest floors above the rooflines of surrounding houses.”6 The elevator takes residents to an underground parking garage. Bud Goldberg might not have been able to design his own family home but he was able to put his mark in the Gold Coast neighborhood to some degree with this amazing design.

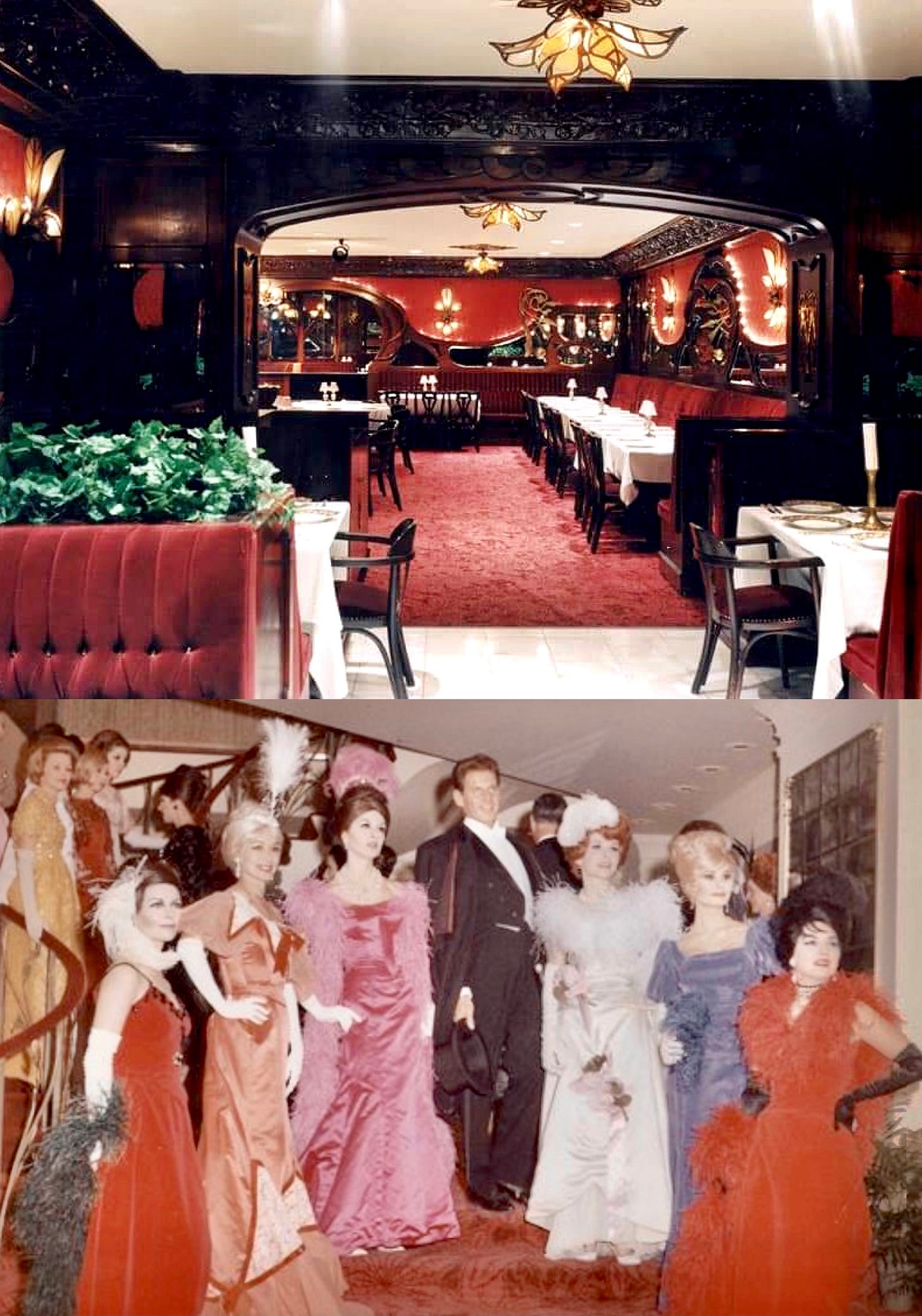

In the basement of Astor Tower he created a near replica of Maxim’s de Paris restaurant, which officially opened in 1963 (the same year as the hotel). Although it became one of the city’s top dining establishments and served as a rival to the neighboring Pump Room, his wife Nancy, who was in charge of the restaurant, decided to close it in 1982, after twenty years of business. Nancy ended up purchasing it back when new restaurants failed in the space. Eventually the Goldbergs gifted Maxim’s to the city of Chicago in 2000, not long after both Nancy and Bertrand died. According to an article from Block Club Chicago, Maxim’s will soon reopen under new owners who live in the Astor Tower, who hope to turn it into a private social club for the neighborhood.

Although a designer of towering buildings, Goldberg wasn’t too fond of the condominium hi-rises that began to encroach his Gold Coast neighborhood, including one directly across the street from his own home. According to a Chicago Tribune article from 1973, Goldberg expressed his concerns: “I don’t know what they have done except destroy the environment that gave Astor its value. These people came to partake of the quiet and the green, and they soiled their own nest. They brought more cars and more people, after building a wall to close off the sun and light. They destroyed the very values they were seeking to enjoy. The quality of architecture concerns me. These buildings provide shelter, heat, space - but there’s no pleasure from the construction of space, which is one meaning of architecture. It has the same relationship to architecture as taking aspirin has to prescribing medicine.”7

In 2014 Goldberg’s home on Astor sold for $7.4 million by its then owner, Nicholas Pritzker, who had lived in the house since the late 1980s. The buyers did a complete gut job, only leaving the facade (so basically the value was in the land). So whatever was left of Goldberg’s personal residence for thirty-four years was officially gone. Besides living in his mother-in-law’s home, Bud also briefly resided in his famed River City building, specifically a three-bedroom triplex combined with a studio apartment at 1702/04. Would the architect be happy with the brutalist building’s recent (and controversial) renovation that has resulted in the interior atrium being painted a trendy bright white? River City’s new owners posted a quote by Goldberg, in which he supposedly said: “I hope that what my architecture has done is allowed enough freedom, enough creative potential from the people using my buildings to develop their own architecture, to develop their own activity, their own patterns of living, their own exploration of how to use space for living.”

Although I didn’t cover all of Goldberg’s residential designs, a fascinating part of his long and varied career, I hope to further investigate it in a future article down the road.

Modern in the Middle (2020) by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino.

Interview with Betty J. Blum, Chicago Architects Oral History Project, 1992.

Quote from historic preservationist Jeanne M. Lambin in Modern in the Middle (2020) by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino.

http://modernmag.com/florsheim-goldberg-an-extended-conversation/

http://bertrandgoldberg.org/projects/astor-tower/

AIA Guide to Chicago, Third Edition, 2014.

http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1973/05/20/page/217/article/astor-street