Architect Homes: John Wellborn Root

Earlier this month I mentioned how I’ll be writing a never-ending series on architect residences located across Chicagoland. This is the second part, focusing on well-known 19th century architect John Wellborn Root and his house in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood, where a considerable number of architects lived (and sometimes worked), including Bertrand Goldberg, David Adler, Andrew Rebori, Benjamin Marshall, James F. Eppenstein, and even Frank Lloyd Wright for a short period of time. Their residences will be covered in later sections.

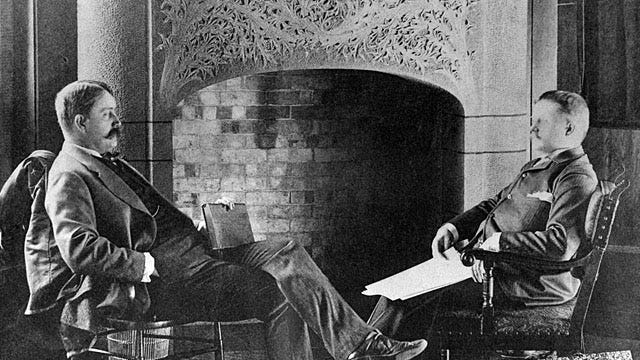

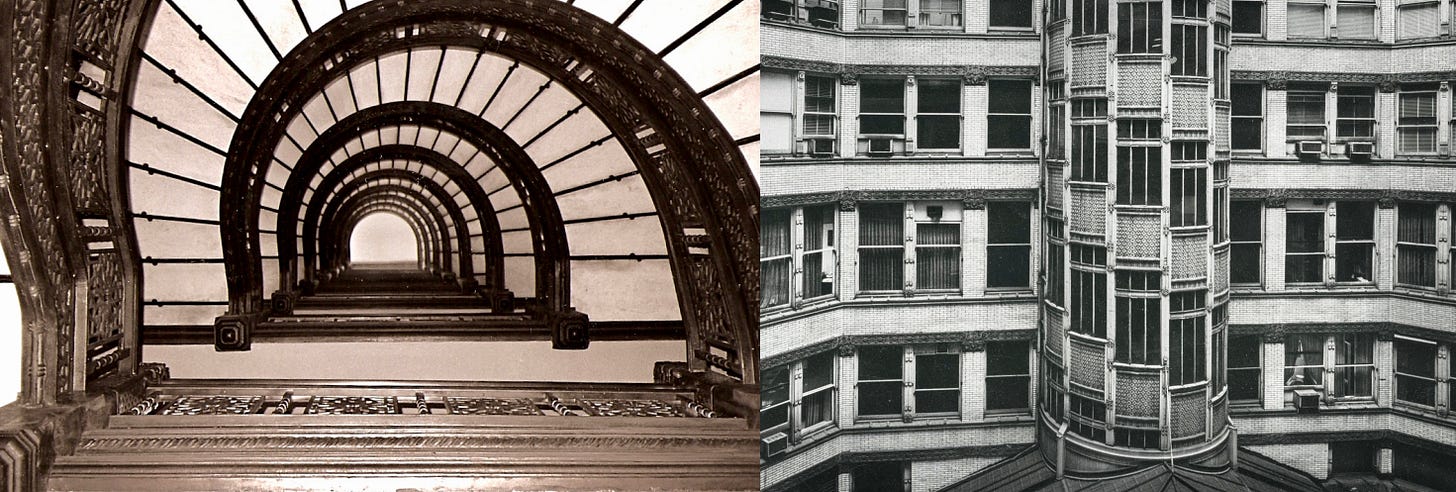

John Wellborn Root (1850-1891) of the architectural firm Burnham & Root was one of the founders of the Chicago School of architecture. He developed both steel-frame construction and the floating raft system and was also influential in creating a purely American style of architecture free of European forms, much like his contemporary Louis Sullivan. Both Root and Sullivan were greatly impacted by the work of American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, which is most evident in Root’s design for the Rookery where Burnham and Root’s offices were located upon its completion in 1888.

Living near wealthy clients and prospective commissions has its advantages, so it’s no surprise that a number of architects lived in the Gold Coast, including Root. Once a frog-infested swamp, developer Potter Palmer transformed the area with landfill, then convinced the city to build a street (Lake Shore Drive) adjacent to his forty-two room mansion that not only enhanced his property values but also attracted other affluent families to move here from Prairie Avenue and the South Side. Because Palmer owned most of the land in the Gold Coast, he was able to chose his potential neighbors. Property was only sold to people who Palmer would have as guests at his own dining room table. One of those people was the real estate developer James L. Houghteling (1855-1910) of Peabody, Houghteling & Company, who lived in the neighborhood in a home on Banks Street.

In 1887 a group of townhouses on Astor Street was designed for Houghteling by the architectural firm of Burnham & Root. Originally a set of four, the southernmost townhouse was torn down for the neighboring Astor Tower Hotel in the 1960s by future resident of the neighborhood, architect Bertrand Goldberg. The frontal peaked dormer was characteristic of Root’s commercial and residential work. Although an overall coherent design, the row homes exhibit some historical influences with its mix of Tudor and Queen Anne elements that greatly contrast with the many ground-breaking buildings that had already materialized from their firm.

Just thirteen years earlier, Burnham & Root’s first residential commission, the John B. Sherman House (1874), was a strikingly simple design of pressed brick and sandstone, completely out of step with the extravagantly historical-revival mansions that lined Prairie Avenue at the time. Even architect Louis Sullivan was impressed, writing about Sherman’s house in his The Autobiography of an Idea: “There, on the southwest corner of Prairie Avenue and Twenty-first Street, (my) eye was attracted by a residence, nearing completion, which seemed far better than the average run of such structures inasmuch as it exhibited a certain allure of style indicating personality.”

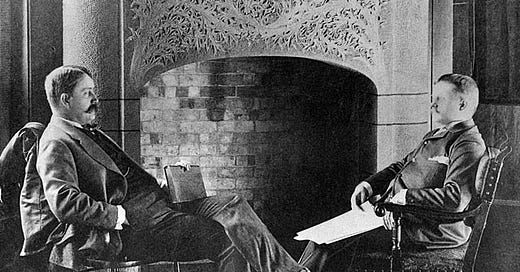

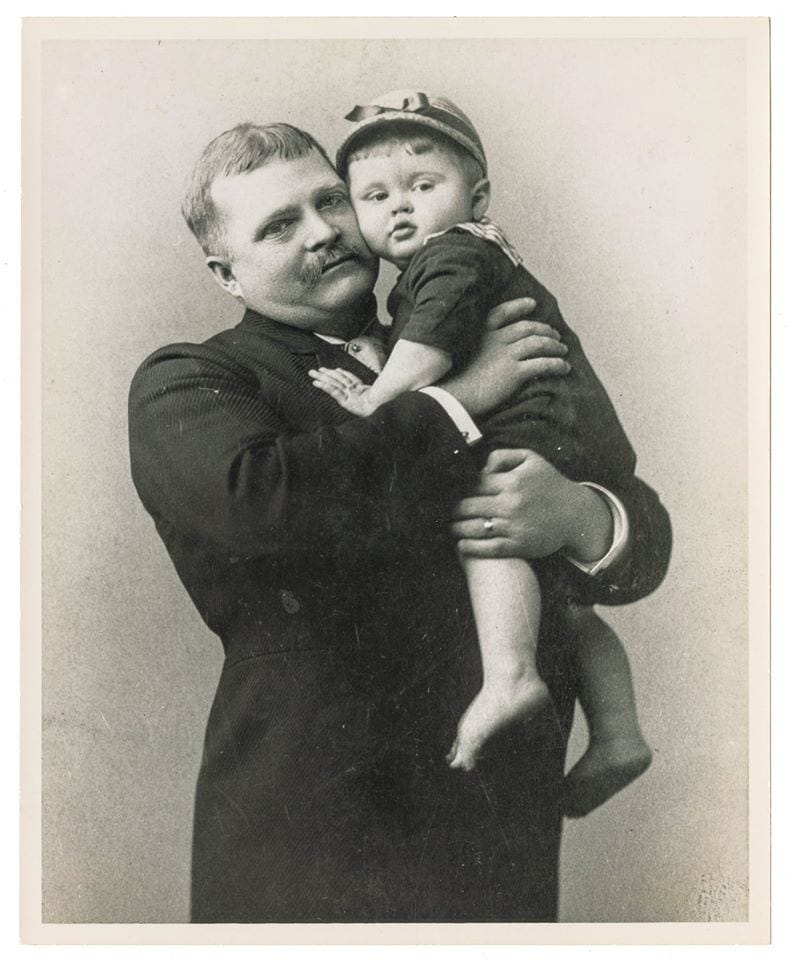

It’s fascinating to see where architects opted to live, particularly the ones who created their own homes, either from scratch or extensive remodeling/rebuilding. When the Houghteling townhouses were completed, Root must have liked them as he moved into the middle one, but unfortunately died of pneumonia in the home after just living there for a few years. He was only 41 years old. His death sent shock waves through the architectural community. The firm had just received its largest and most important project, the World’s Columbian Exposition, which was only in the planning stages at the time. But it also might have been the reason for Root’s premature death. He was traveling around constantly, drawing and redrawing, participating in never-ending speaking engagements, and personally guiding people around the fair site while still carrying out all the other work at the office.

Days after his untimely death in January of 1891, the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Saturday he took a Turkish bath and later at his own house thoughtlessly stepped into the street to hand a friend to her carriage, becoming slightly chilled in so doing. During Sunday he received at his hospitable home a visit from the Eastern architects visiting the scene of the World’s Fair, and that night he was seized with a severe chill, which proved the beginning of a fatal illness.” Root’s partner of eighteen years, Daniel Burnham, was said to have paced the floor of Root’s home, waiting for updates from the doctor. When Burnham heard of Root’s death, his only words were “Damn! Damn! Damn!” Such a response was probably due to Burnham’s realization of two possible scenarios: the firm could not go on without its ‘creative genius’ and that he alone would have to plan and execute the World’s Fair. One can only imagine what role Root would have played in the overall look of the World’s Columbian Exposition, which turned out more classical than progressive due to Burnham’s influence. Louis Sullivan later dismissed it: “the damage wrought by the World’s Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer.”

Root’s funeral was held in the Astor Street home, then his remains taken to Graceland Cemetery for interment. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, in Chicago for the planning and design of the World’s Columbian Exposition fairgrounds, stayed for the funeral. Although Root always tried to break away from tradition, the members of his architectural firm, including Charles Atwood and Jules Wegman, designed a Celtic cross made of red Scottish granite. It honored not only Root’s ancestry but a form he had personally admired. A panel depicts one of Root’s drawings, the entrance to the now-demolished Phoenix Building (1887-1957). Just over twenty years later, Burnham would join Root in death and was buried nearby on a wooded isle in Graceland’s Lake Willowmere. The lake had been created by Burnham’s former employer William Le Baron Jenney in the 1870s. Accessed by a bridge, the island marks Burnham and his wife Margaret’s remains with a granite boulder, next to the graves of their three sons John, Hubert, and Daniel Jr. James L. Houghteling, who commissioned Root’s townhome, is also buried in the cemetery along with Root’s own son John Wellborn Root Jr., who founded the architectural firm of Holabird & Root. The markers of father and son share the same red granite stone.

Although Root designed over 300 structures during his partnership with Burnham, only a handful of their buildings survive in Chicago: just three commercial buildings (the Monadnock, the Reliance, and the Rookery) and ten residences, including the Houghteling Townhouses, which last sold in September of 2015 for $2.2 million. A lot of their work was destroyed during the urban renewal period of the 1950s and 60s, yet surprisingly demolition still continues into the present time. In 2018 a historic 1884 Burnham and Root-designed house in Champaign, Illinois was torn down for a parking lot. It’s a shame another building by this influential architect was lost instead of preserved for future generations. If you’re looking for more of their lost work, please check out Urban Remains, which has a great collection of archival photos.

Sources:

A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery by Barbara Lanctot

Architects’ Gravesites: A Serendipitous Guide by Henry H. Kuehn

The Architecture of John Wellborn Root by Donald Hoffman

The Autobiography of an Idea by Louis H. Sullivan

Graceland Cemetery: A Design History by Christopher Vernon

Images of America: Chicago’s Historic Prairie Avenue by William H. Tyre

Lost Chicago by David Garrard Lowe