Modernism...in Elmwood Park

As a teenager I explored every single part of Elmwood Park, an inner-ring suburb directly west of the Montclare and Galewood neighborhoods in Chicago. Once a farming community, the village was established in 1914 in order to prevent annexation into the city. Although I didn’t grow up here, I practically did as many of my close friends lived on both sides of the train tracks that splits the town into two separate sections. In 1926 developer John Mills purchased 245 acres that had originally been part of River Grove’s Elmwood Cemetery from Paul Stensland, president of the Milwaukee Avenue State Bank in Chicago. That same year Mills started constructing brick bungalows north of the tracks until the beginning of the Great Depression. He would end up building 1600 in total.

After World War II the building boom started up again, but this time south of the tracks with thousands of single-family tract homes constructed between 1945-60. To say all the homes look alike in Elmwood Park is an understatement, which isn’t helped with the similar-sounding street names like 75th Ave and 75th Ct. But surprisingly there is some unique architecture to be found here, located near the Oak Park Country Club. One of these homes is a modernist design by Robert Bruce Tague (1912-1984) and Crombie Taylor (1914-1999).

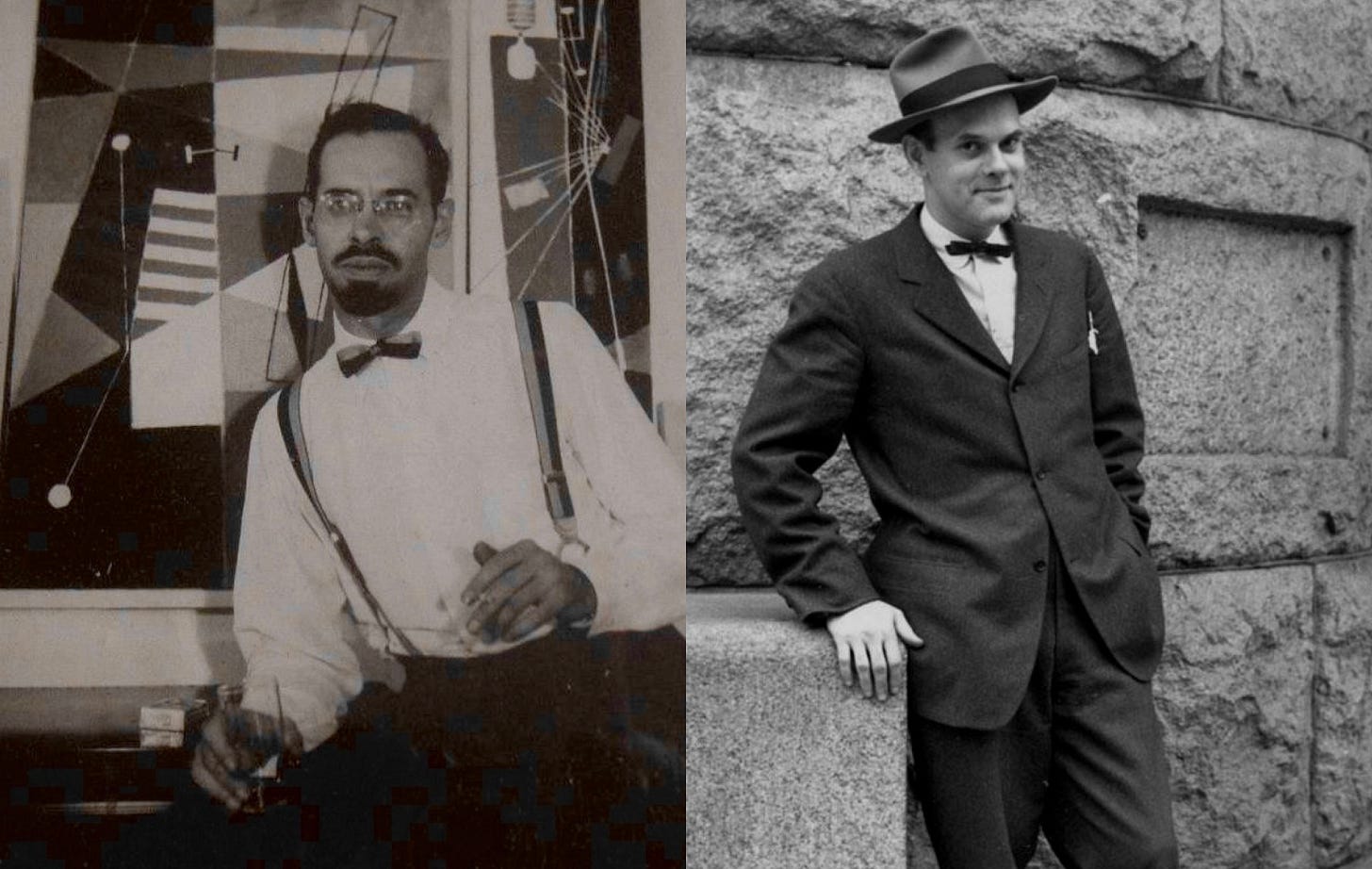

Before Ludwig Mies van der Rohe took over as head of the architecture department at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), the former Armour Institute was already exposing its students to new, modernist ideas. One of the students in the architecture program between 1930-1935 was Robert Bruce Tague, who earned his Bachelor’s in Architecture in 1934, followed by a Master of Science in Architecture the next year. After seeing George Fred Keck’s House of Tomorrow and Crystal House at the 1933-34 Century of Progress exposition in Chicago, Tague sought out the modernist architect to serve as his master’s thesis advisor. According to Tague in a 1983 interview, “Keck was the only major architect in Chicago doing modern.” While completing his thesis, Tague began doing design work for Keck, eventually becoming one of the main draftsmen at Keck’s architectural firm between 1935-56.

Starting in 1939 Tague taught architecture and drafting at the New Bauhaus (or Institute of Design), where he met another instructor named Crombie Taylor, who eventually became its director. Although a modernist designer, Taylor was also a historian and preservationist responsible for a number of restorations, including Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building. The two men were connected together for nearly a decade under the banner Crombie Taylor Associates. Tague recalled that he “stamped the plans” as “architect of record” because Taylor didn’t have an architect license in Illinois.

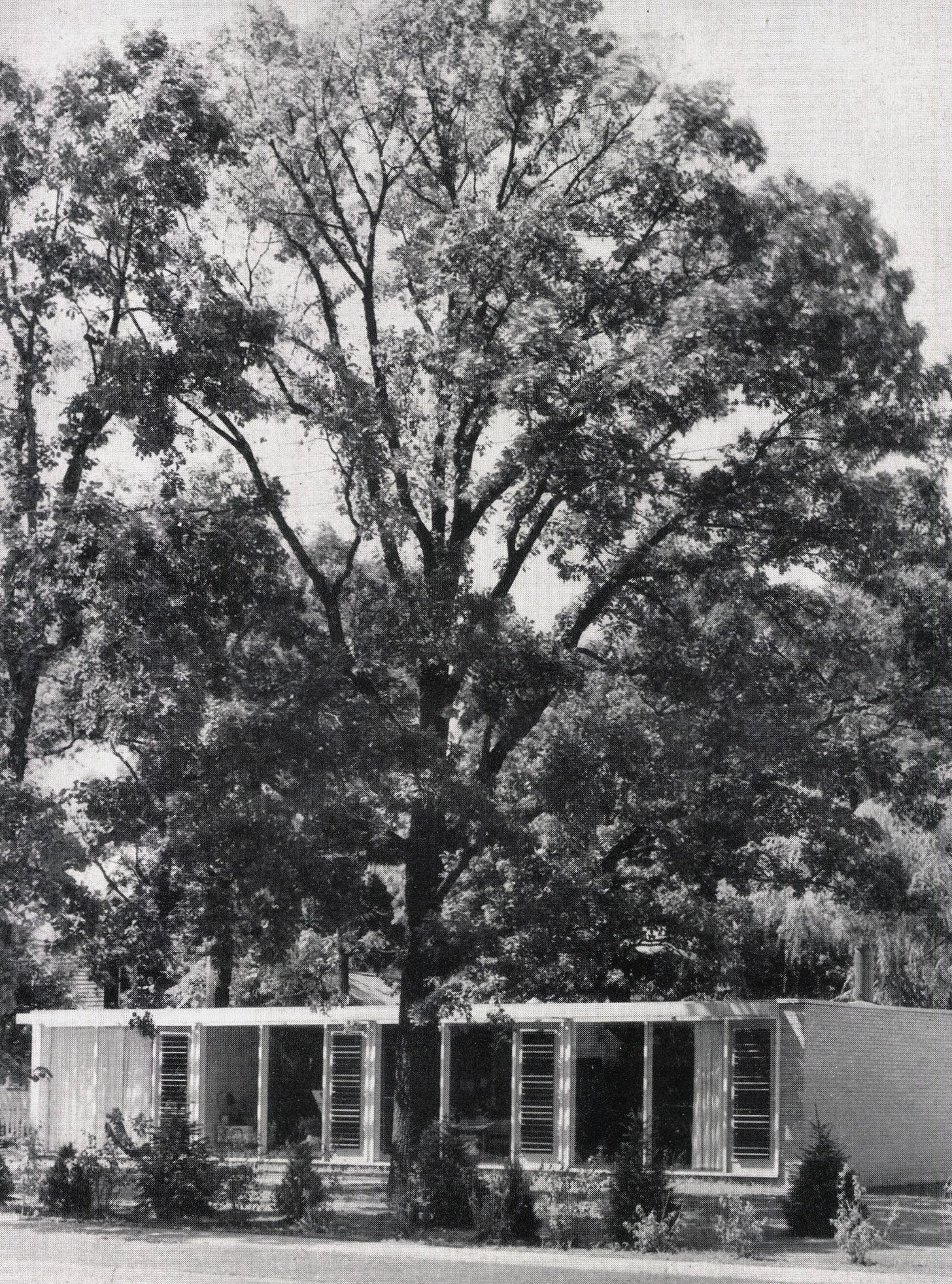

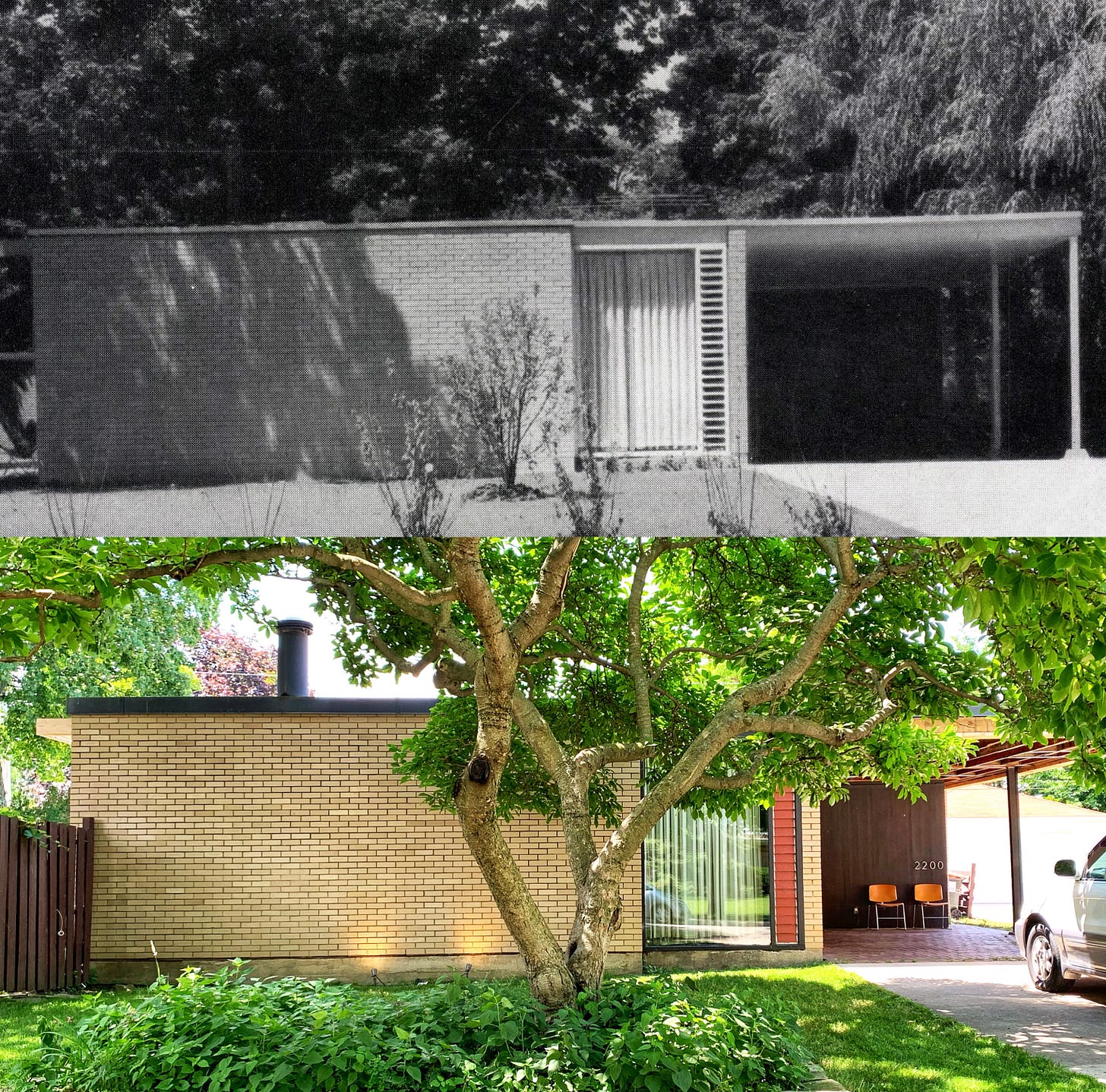

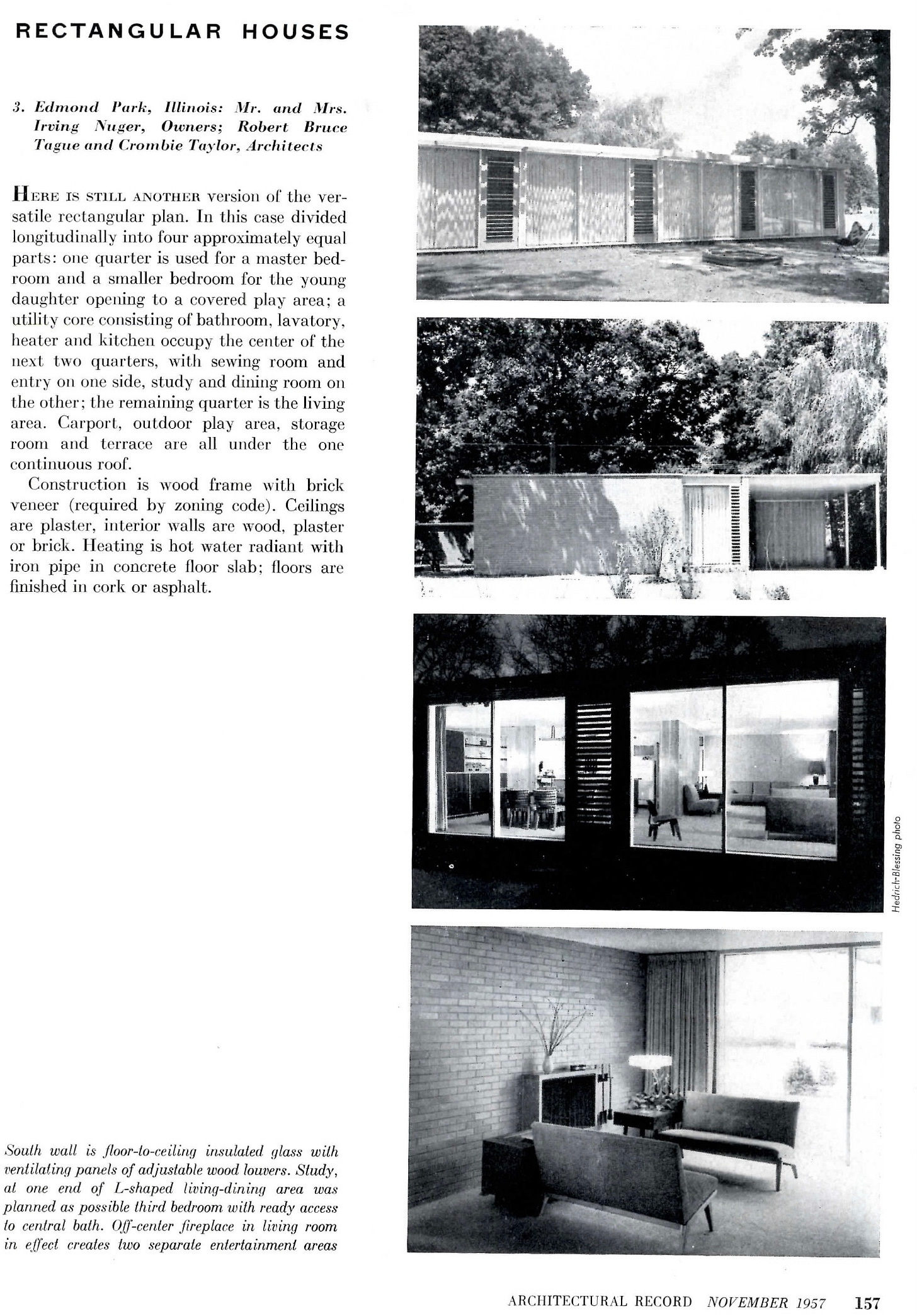

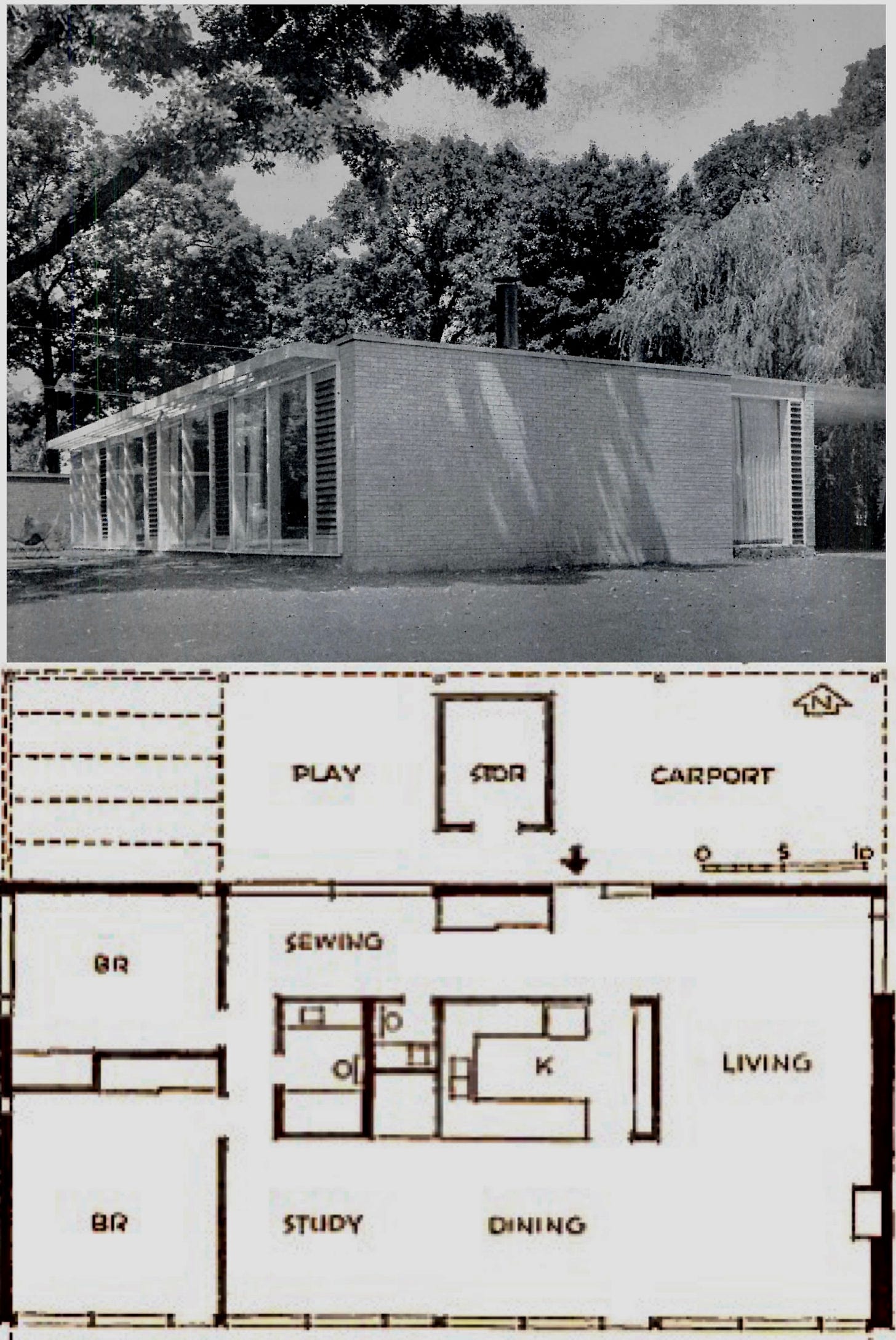

In 1952 Tague and Taylor designed “a simple little house” at 2200 N. 77th Ave in Elmwood Park for Irving Nuger (1920-2005) and his wife Jean and daughter Paula, who would soon be joined by siblings Donna and Philip. Jean Nuger was actively involved in local politics, even serving as the president of the Elmwood Park League. Just three years earlier the family had been living southeast at 5323 W. Gladys Ave in Chicago’s Austin community. Their new 1400 square foot home cost them $19,500 to construct.

Nuger’s home was part of a series of architect-designed residences, known as “Quality Budget Houses,” built between $5,000-$20,000 put together in a book by the one-time architectural editor of House & Garden, Katherine Morrow Ford. Alongside her husband and co-author Thomas H. Creighton (the editor of Progressive Architecture magazine), Ford visited and studied 100 post-war modernist homes. Some of the architects highlighted in her book were Richard Neutra, Paul Rudolph, Victor Gruen, Paul Schweikher, and Tague’s mentor George Fred Keck. The same year the Nuger residence was designed with Tague, Taylor also worked with Gyo Obata on a now-demolished home in suburban La Grange. It was also featured in Ford and Creighton’s book.

Described as “a way to assure economies without sacrificing quality,” these homes offered owners the chance to produce their “own little architectural masterpiece, within (their) budget.” The program suggested to builders that it was best to buy local, durable materials and use natural finishes to save money instead of covering up the interior spaces with plaster and wallpaper. Nuger’s home had an openness due to the kitchen and bathrooms grouped together “around a central utility core.” Architects gave the possibility of expansion as a covered play area for two-year-old Paula Nuger could become an addition while the room marked as Irving Nuger’s study could be turned into a third bedroom.

In a 1983 interview Tague described a typical Keck house as “a common brick box with a forty-five degree roof, a trim line with big dormers, with attached garage…your larger glass areas facing the private side.” Although the Nuger design isn’t exactly a copy and paste of a George Fred Keck home, it does share some similarities, specifically in its wall of glass with sunshade overhangs and adjustable louvers. Keck had pioneered passive solar homes. After 1940 the major spaces of his buildings were always oriented for southern exposure while also incorporating overhangs to keep out the sun and louvered panels for ventilation. Tague learned the importance of both site planning and solar orientation. The Nuger house also optimized the use of solar energy with double-glazed windows, known as a “Twindow,” that are made and sealed in a factory. The home’s southern side is now hidden behind a wooden fence and little Paula Nuger’s play area gone, but otherwise the home looks to be in pretty good shape considering it’s almost 70 years old.

Starting in 1966 Tague partnered with former Keck associate, Tristan Meinecke (1916-2004), designing numerous condominiums around Chicagoland, including in Elmwood Park. He was also an abstract artist, as was his partner Meinecke, usually creating mixed media collage paintings. Tague had called himself “a rebel” as an architect, clearly influenced by modernists who had come before him. In 1976 architect Stuart Cohen referred to Tague’s work standing “between the houses of the new prairie style and the structurally modulated and panelized residential work of Keck and Keck during the 1940s and 1950s and Mies van der Rohe’s residential projects of the 1950s.”

The fact that the Nuger home with such an impressive architectural pedigree exists at all in nondescript Elmwood Park is incredible. That it survives in almost original condition is an absolute miracle. Tague and Taylor’s names are not well-known outside of architecture geek circles but that doesn’t mean their work is undeserving of recognition. With the demolition of Erne and Florence Frueh Houses I and II in Highland Park, two residences designed by the architects separately, it is important to acknowledge their rightful place in modern architecture. Fortunately this “simple little house” survives as evidence of their genius.

Sources:

Building + Living, Journal for the Design and Technology of Construction, Space, and Equipment; 1954.

Chicago Architects by Stuart E. Cohen

Chicago Architects Oral History Project: Interview with Robert Bruce Tague, 1983.

elmwoodpark.org

Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975 by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino

Quality Budget Houses: A Treasury of 100 Architect-Designed Houses From $5,000 to $20,000 by Katherine Morrow Ford and Thomas H. Creighton.

https://socalarchhistory.blogspot.com/2018/09/james-and-katherine-morrow-ford-thomas.html

villageofelmwoodpark.wordpress.com