Frank Lloyd Wrong Part 2

Okay, unlike Frank Lloyd Wright, I fully admit that I am a liar. Back in June, I had promised to write a multi-part “summer” series discussing what I believe is wrong with Frank Lloyd Wright. Well, to be perfectly honest with you, I completely forgot about it. After decades of having an on-and-off relationship with the guy, I see this as a positive sign. Perhaps I’m finally over him? Maybe I’ve truly moved on? At long last, I can actually live with *my life*. Joking aside, with the official last day of summer (September 22nd) earlier this week, let’s continue to explore, as promised, why I believe the world’s most famous architect should be referred to as Frank Lloyd Wrong (there may possibly be a Part 3).

Let’s start at the very beginning. How did this guy get to be this way? Anna Lloyd Jones was an overbearing, possessive, and indulgent mother who instilled in her first-born child the idea that he was a prince, predestined to achieve something great. He certainly acted like it was true. Even later on, architect Philip Johnson said that Frank thought he was “born full-blown from the head of Zeus.” In my opinion, there is no doubt Frank had talent, whether it was natural or learned, but his ample egotism spoke of something else. It tells me that he was incredibly insecure, especially around people who might have exceeded him in abilities or were more formally educated, but I’'ll get to that in a minute.

Anna decorated her son’s nursery with engravings of English cathedrals and encouraged him to play with geometrically-shaped Froebel blocks, which shows that Anna was determined he grow up to to be an architect. Already wearing his trademark cape, a teenage Frank was admitted to the University of Wisconsin-Madison as a special student in 1886, where he studied under Allan D. Conover, a civil engineer and architect. Although he was only taking classes part-time, Frank still failed to attend regularly, as noted in a progress report (seen below). He dropped out of school after two semesters. Did he arrogantly think he was too good for school? Who knows? It was not required to have a degree in architecture to become a successful architect in the late 19th century. However, Frank’s mentors, Joseph Silsbee and Louis Sullivan, both studied at MIT, and later, his colleagues, such as Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, had graduated with degrees in architecture. I believe that’s why Frank acted the way he did. While Anna instilled in her son a sense of overconfidence, he knew deep down that it wasn’t entirely true. This might explain why Frank was so dismissive of other people’s talents, even though he probably would not have succeeded without their contributions (I’ll get to those relationships, I promise).

Did Anna create a monster? I’m not sure. She clearly had a negative impact on how he turned out. But there seems to be a misogynistic element to some of the things written about her. I remember during tours at Frank’s Home & Studio in Oak Park learning that his wife Catherine was so scared of her mother-in-law that she would often hide in a closet. Anna certainly had a strong personality and was known for her temper. But she was also ahead of her time. Frank’s youngest sister, Maginel, said her mother was “emancipated before the emancipated woman became the vogue.” A spinster until the age of 29, Anna was taller than her husband, rode horseback like a man, sometimes dressed like a man, and often walked alone unattended.

Frank inherited his absentee father’s charm as biographer Meryle Secrest described William Wright as “one of life’s darlings: he never met a single person who did not like him,” whether as a popular musical performer or “mesmerizing lecturer” and preacher. He constantly moved from place to place during Frank’s somewhat chaotic childhood, working as a musician, composer, poet, minister, lawyer, and doctor. Not to be revisionist, but it sounds like William had ADHD. When Frank was only a teen, he described his father as “deep in the study of Sanskrit,” one of many inexhaustibly intellectual and creative pursuits. This might also explain a few things about Frank himself. Could he have inherited his father’s ADHD disorder? The architect was known for risky behavior, impulsivity, procrastination, and spending money even when broke. I’m not suggesting this is the reason why we should call him “Frank Lloyd Wrong” but it’s something to think about as I share more about him.

Another thing that father and son had in common: abandoning their families. As Ada Louise Huxtable wrote, William Wright had created “an unstable household [that led to a] constant lack of resources [and] unrelieved poverty and anxiety.” After Frank’s parents separated when he was just 14, later to divorce, William was in “perpetual motion,” residing in twenty towns and seven states. Frank did not attend the funeral of his father, who died in 1904.

In 1909, Frank left his wife Kitty and their children in Oak Park while he ran off to the Plaza Hotel in New York City with his mistress (and former client), Mamah Borthwick Cheney. They traveled first class on a luxury liner to Europe, where they stayed for the next year. Yet, in a 1910 letter, Wright complained that he had no money to pay for his wife’s bills or his kids’ music lessons. In the Ken Burns documentary, David Wright recalled his father sticking them with a $900 grocery bill (that’s over $31,000 in today’s money). The family was forced to rent out part of their Oak Park home to make ends meet (I wrote about who rented it almost two years ago). It appears that Frank was repeating the same behaviors of his dad.

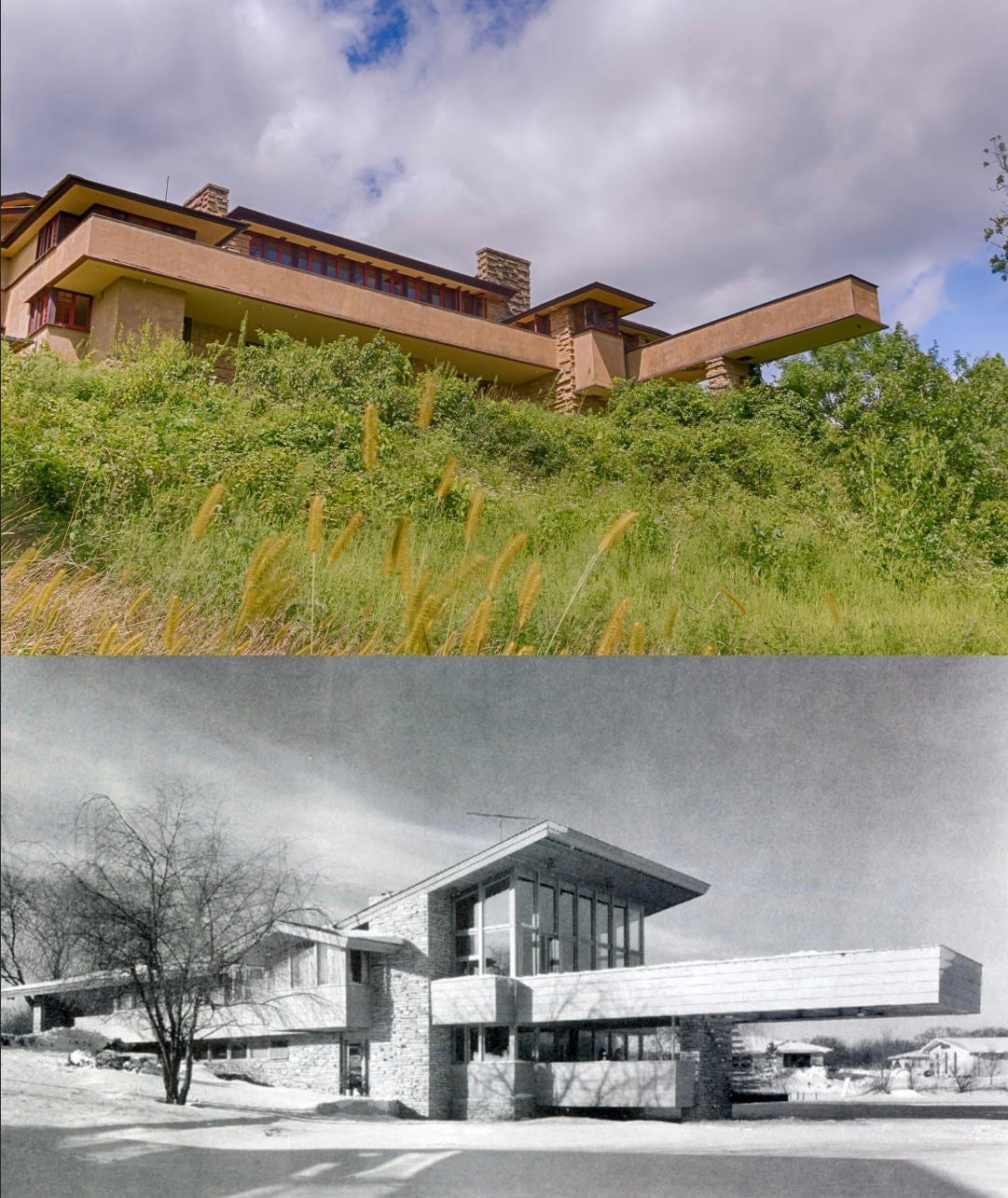

Money (or not having it) was a recurring theme throughout Frank's life, even in his later years. In 1954-55, the architect threatened to leave his home state of Wisconsin, where he had been born nearly 88 years earlier. Why? The state supreme court had ruled that the Taliesin Fellowship was not an educational institution and, therefore, was subject to taxation. However, all that changed when he accepted a $10,000 check to help pay back taxes at a tribute dinner alongside then-Governor Walter Kohler. Go back fifty years and read similar stories of Frank desperately needing money. For example, his client Darwin Martin, who lost millions in the Stock Market Crash of 1929, went on record declaring that Wright had not paid back a single dollar of the total of $70,000 he lent to the architect. What a guy!

Speaking of exploitation, how disrespectful was Frank to his colleagues and later to his students at Taliesin? Let’s not forget the reasons he established the school in the first place. Out of work and nearly forgotten, Frank founded the Taliesin Fellowship in 1932 because he craved two things: money and attention. He certainly achieved that with the impressionable apprentices, whose yearly fees were comparable to those of a typical college education. Except these young men and women did not merely learn at the feet of their master; they were also expected to farm his land, renovate his buildings, create furniture, and work in the kitchen, where they prepared food and served meals. As I mentioned in Part 1, architect Harry Weese described Frank as “not totally honest” in his dealings with the Fellowship. He succeeded in turning the kids into “sycophants” and “slaves.” While some think of Taliesin as a self-sustaining utopia, I see it more like a self-serving, borderline abusive cult. How normal was it when you remember that Frank’s third wife, Oglivanna, arranged a marriage between her son-in-law and the only daughter of Joseph Stalin during the height of the Cold War?

I find it intriguing that Don Erickson, who apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright from November 1948 to April 1951, happened to be at Taliesin just before the creation of “the birdwalk.” Erickson’s father was a master stair builder who worked with metal, likely influencing his son’s most notable project, the Birdcage Apartments in Chicago, which features a freestanding steel-rod staircase. “The birdwalk” is a long balcony on top of two 40-foot steel I-beams that juts over Frank's home and the valley below. It was supposedly constructed for Olgivanna sometime between 1951 and 1953. Erickson’s residential design in suburban Park Ridge, the Charles Matthies House from 1958, has the most insane cantilevered walkout I’ve ever seen. Was there any other apprentice who so boldly designed a projection like this? Am I suggesting that Frank might have gotten the idea from his apprentice? Perhaps. But only because of my own frustrations dealing with the endless speculation and ongoing debate about the extent of Frank's own contributions to the work of Adler & Sullivan. If people think Frank influenced Sullivan, then why can’t I engage in similar conjecture? Especially in his late career designs where a number of apprentices were known to participate in the design process (I hope to discuss this further in Part 3). I believe the famous quote “good artists copy, great artists steal” is applicable to Frank throughout his professional career.

If we rewind back to his Chicago years, I have to discuss what a jerk he was to those working alongside him—Walter Burley Griffin, Marion Mahony Griffin, and others at the Oak Park Studio (but also Robert C. Spencer and the architects at Steinway Hall who I plan to discuss further in Part 3). As I mentioned earlier, the Griffins were highly educated, and it is telling that Frank surrounded himself with people like them to compensate for his own shortcomings (even apprentices like Wes Peters spent two years at MIT before joining Taliesin).

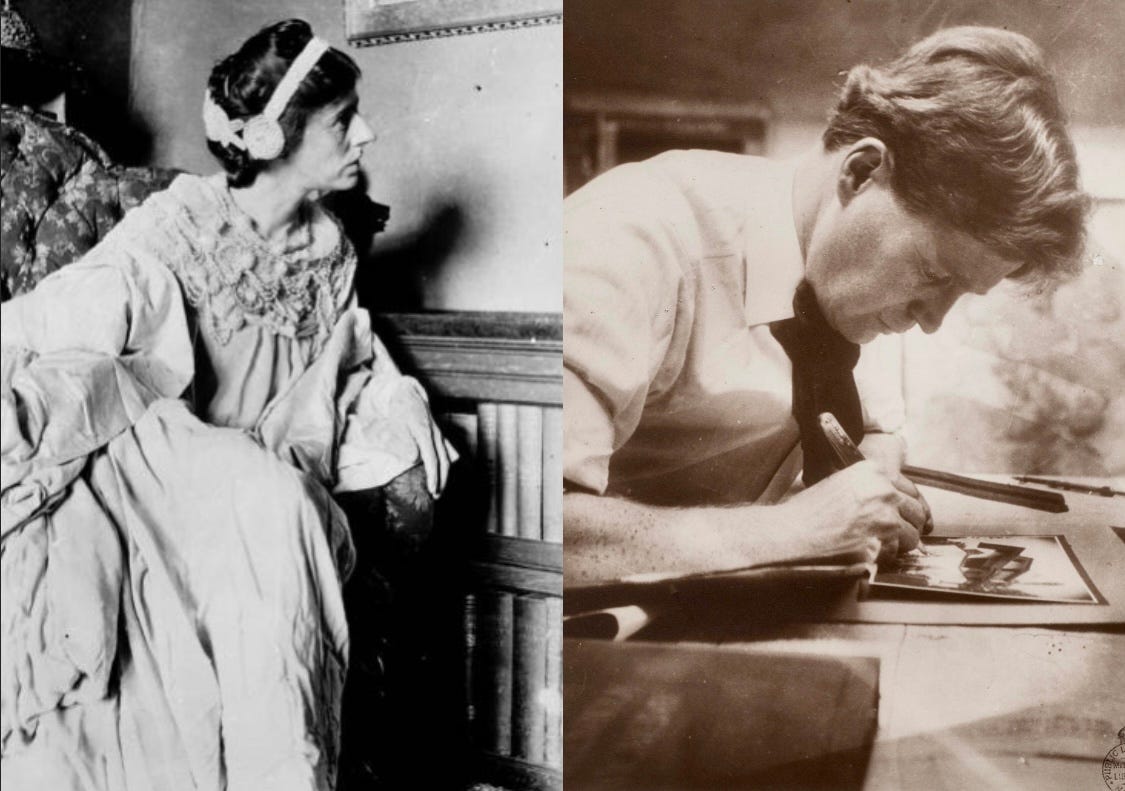

Marion was a pioneering woman architect (the first licensed in the state of Illinois) constantly overshadowed by her male colleagues. Frank’s “right hand woman” for over a decade, she was technically his first employee and was known as one of the greatest delineators, creating watercolor renderings of buildings and landscapes that most people today associate with him. She contributed nearly half of the drawings included in his influential Wasmuth Portfolio (architects such as Le Corbusier, Peter Behrens, Rudolph Schindler, and Richard Neutra reportedly all had copies). It not only helped to elevate Frank's profile internationally but also established his genius. Later, she would oversee the drawings that helped her husband win the international competition to design Australia’s new federal capital city of Canberra. Remember the saying “behind every great man is a great woman.”

In 1898, three years after Frank hired Marion as his assistant, he added a studio next to his Oak Park home, which became an architectural laboratory. I find it suspiciously convenient that Marion’s thesis project at MIT was titled “The House and Studio of a Painter,” in which she presented a suburban home connected to a three-room workplace by a colonnade. The exterior design of Frank’s studio is strikingly similar with its two-story drafting room and small library balanced in between with loggia columns that feature storks or “wise birds” that are now attributed to Marion herself. Although she worked for Frank for fifteen years and lived to the age of 90, she remains relatively unknown in the U.S. He never acknowledged her important contributions that led to his success, dismissing Marion as a “great designer of isolated details” but “not an architect or planner.” Unsurprisingly, she bitterly resented her connections to Frank, even refusing to use his name in an unpublished memoir. Barry Byrne, who worked in the Oak Park Studio, thought that Marion was “the most talented member of Wright’s staff, and I doubt that the studio, then or later, produced anyone superior.”

Marion’s husband, Walter, worked alongside Frank from 1901 to 1906, and not only developed innovations such as the L-shaped and open-concept floor plans, as well as the carport, but he also oversaw significant projects as office manager. He supervised the Willits House, regarded as one of the first examples of the Prairie Style, and the Larkin Building. Walter brought experimental ideas to the firm, like “breaking the box,” which was a way to create more open, multi-level spaces—a concept that was realized at Larkin. Due to his expertise and talents, Walter was put in charge while Frank traveled to Japan in 1905 (notably, Frank borrowed money from Walter for the trip). Upon his return, however, Frank did not make Walter his partner, as had been anticipated when he first joined the studio, nor did he repay him. Instead, Frank offered Walter some Japanese prints. Walter quit in disgust. Throughout his life, Frank minimized Walter’s contributions, dismissing him as a mere draftsman, despite the fact that Walter was a licensed architect with a degree in architecture—credentials that Frank could not claim. Typical of narcissists like Frank is their tendency to manipulate, use, and discard people from their lives.

When Frank shut down the Oak Park office in 1911, he tried to derail the careers of those who had worked for him, accusing them of stealing *his* architectural property. He claimed sole credit for organic architecture, writing, “This is piracy, lunacy, plunder, imitation, adulation…” in an article titled “In the Cause of Architecture,” published in the Architectural Record in 1914. He presents himself as a lone genius (I wonder where he first got that notion?), lying that he was “alone in my field” and conveniently forgetting all the collaborative ideas shared among his peers, first at Steinway Hall (I promise to elaborate on this in Part 3) and later in Oak Park. Marion wrote in her memoir that Louis Sullivan was the main force behind what became Prairie School architecture: “Wright's early focus on publicity and his claims that everybody was his disciple” were untrue. Instead, a group of individuals—including Wright, Spencer, Mahony, Griffin, Myron Hunt—who were all influenced by Sullivan’s philosophy and shared an office/drafting studio at Steinway, contributed to its development.

Even his own son, John Lloyd Wright, admitted that the five men and two women (we can’t forget about Isabel Roberts - I wrote about her several years ago) who he recalled working at the Studio were “making valuable contributions to the pioneering of modern American architecture for which my father gets the full glory, headaches and recognition today!”

Okay, I have written enough for Part 2, but can I just say that if one more person tells me how much Frank Lloyd Wright influenced Louis Sullivan, rather than the other way around, I will scream. That’s probably what led to this three-part rant in the first place: working in an Adler & Sullivan-designed building and the only thing people want to talk about is, you guessed it, Frank Lloyd Wright. Although I admit it’s gotten better. More Sullivan, less Wright. Enough has been written about the man (and I apologize for contributing to the problem) but if the world must have another book about him, I hope it will be mine. Look for “Frank Lloyd Wrong” at your local library (or part 3 of this series on Substack before the year is over).

I had wondered about your comments regarding the unlikeability of Frank Lloyd Wright on your prior post. Since reading that, I've also heard others mention similar dislike. This post is quite clarifying. Thank you.