The MacArthur Family and Frank Lloyd Wright

It was exactly a year ago that I wrote a post about “demolition by neglect” by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. I didn’t expect my writing to get much attention, but both the Wednesday Journal and Chicago Tribune gave me a shout-out as did a number of people via supportive emails. The real positive is that the Trust ultimately caved into pressure and have been fixing up the dilapidated property in question. But what I really want to share is the new historical info (at least to me) I recently learned about the Wright Home & Studio (even though I worked there for years, sometimes giving five to six tours a day), proving there is always more to know even on a topic of expertise. The Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright by Lisa D. Schrenk was helpful in writing this article (along with the Oak Park Historic Preservation Commission).

As a docent at the Home & Studio, the years after Frank Lloyd Wright left Oak Park forever in 1911 and the beginnings of the building’s restoration in the 1970s are kind of glossed over during the tour. With the exception of owners Clyde and Charlotte Nooker who opened the carved-up property to the public in 1966, there is hardly any mention of the people who lived there in the 50-year time span after Wright left his wife and children and before it became a historic house museum. It’s surprising because the occupants are worth talking about, specifically the MacArthur family.

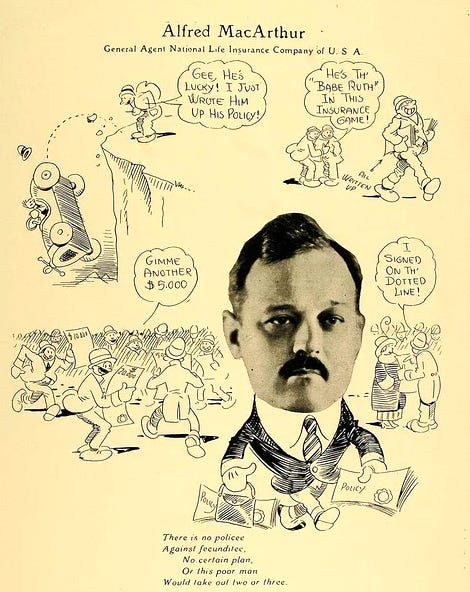

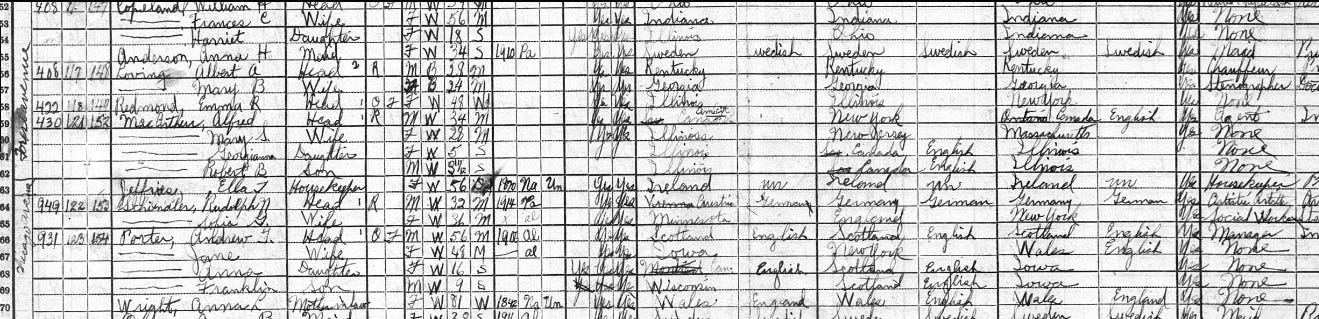

The story goes that Alfred MacArthur, a Chicago insurance executive, had purchased Wright’s former home in Oak Park in 1915 for $15,000 while Catherine Wright and the children moved into the converted studio. This is not true as Wright did not own or clear title to the property - it is a complicated matter with numerous liens, deeds of trust, and lawsuits with Wright’s client Darwin Martin, who was typically in the middle of it due to his many loans to the architect, which at one time totaled $25,283.25 in principal. Martin, who lost millions in the Stock Market Crash of 1929, went on record declaring that Wright had not paid back a single dollar of the total of $70,000 he lent to the architect. In any case MacArthur never took ownership of the building and was simply renting it.

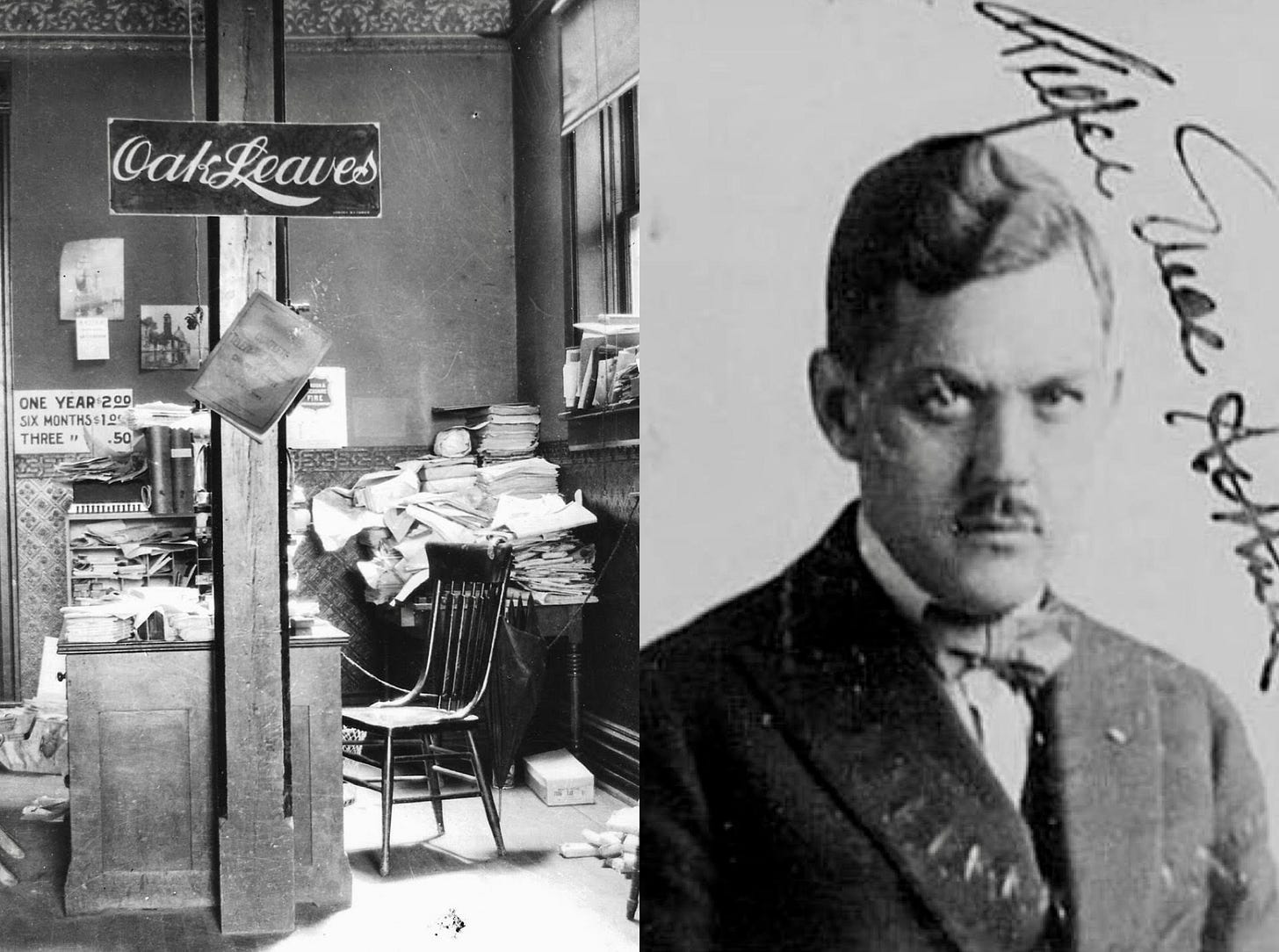

Not long after Alfred moved in Catherine Wright wrote to Darwin Martin in November of 1915, “[T]he MacArthurs have made it the most pleasant for us and have been anxious to live in the old house much as we did-enjoying the playroom and the fireplaces and other features which meant so much to us. They are beginning a little family and it is a great joy to know that it again will serve a growing group of children.” The MacArthurs had a daughter Georgiana in December of 1914, followed by a son Robert in 1916. Unfortunately Arthur’s wife Josephine became ill and soon was confined to the front room of the home. She died at the age of 31 in 1917. The very next year he married Mary Shelton. Alfred’s brother, Charles, a newspaperman who later became a playwright and husband of actress Helen Hayes, lived here briefly during World War I. He’s best known for his collaborations with Ben Hecht, specifically the Broadway play The Front Page, which was based on their time at the City News Bureau of Chicago. Charles had gotten his start with the local newspaper that his family published (I’ll get to that in a minute) - one of his stories had him disguised as a hobo to learn more about the transients who slept at the Oak Park police station.

Alfred worked as a business manager of Oak Leaves, which was published by his younger brother Lawrence “Telfer” MacArthur (who also became chairman of the Pioneer Press) and where a young Charles worked as a village reporter. Oak Parkers rarely advertised real estate in the Chicago newspapers so Oak Leaves was important in connecting the local community to what properties were available to rent/buy as well as the government and social activities of the day. Telfer was also a leader in developing Oak Park’s Lake-Marion-Harlem shopping district.

Living just a block away in the childhood home of Wright’s draftsman John Van Bergen, in 1928 Telfer commissioned another one of Wright’s employees Charles E. White of the architectural firm White & Weber to design a Tudor Revival home with Arts & Crafts influences. The MacArthur family coat of arms is centrally located on the bay window, a common feature in English country houses. A local celebrity in town, Telfer built his new home in the “estate” section of Oak Park known for its large lots but resided there for just six years, selling it in 1934. While he lived there with his wife Ruth and two daughters Jean and Dorothy, it’s worth mentioning Frank and Eva Rosenquist, two Swedish immigrants working as Telfer’s chauffeur and cook, also called the property home.

While Telfer’s life and home is pretty impressive, it’s nothing compared to youngest brother, John D. MacArthur, who lived nearby in Chicago’s Austin not far from where the MacArthur boys grew up. Following Alfred’s footsteps, John built from scratch one of the country’s largest fortunes by selling dollar-a-month insurance policies door to door that later became Chicago’s Bankers Life and Casualty Corporation (he also made money in textiles, oil, and real estate). The third-richest man in the U.S. when he died in 1978, the Chicago-based John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation has an endowment of $7 billion and annually awards $625,000 no-strings-attached “Genius Grants” to around two dozen creative individuals in diverse fields.

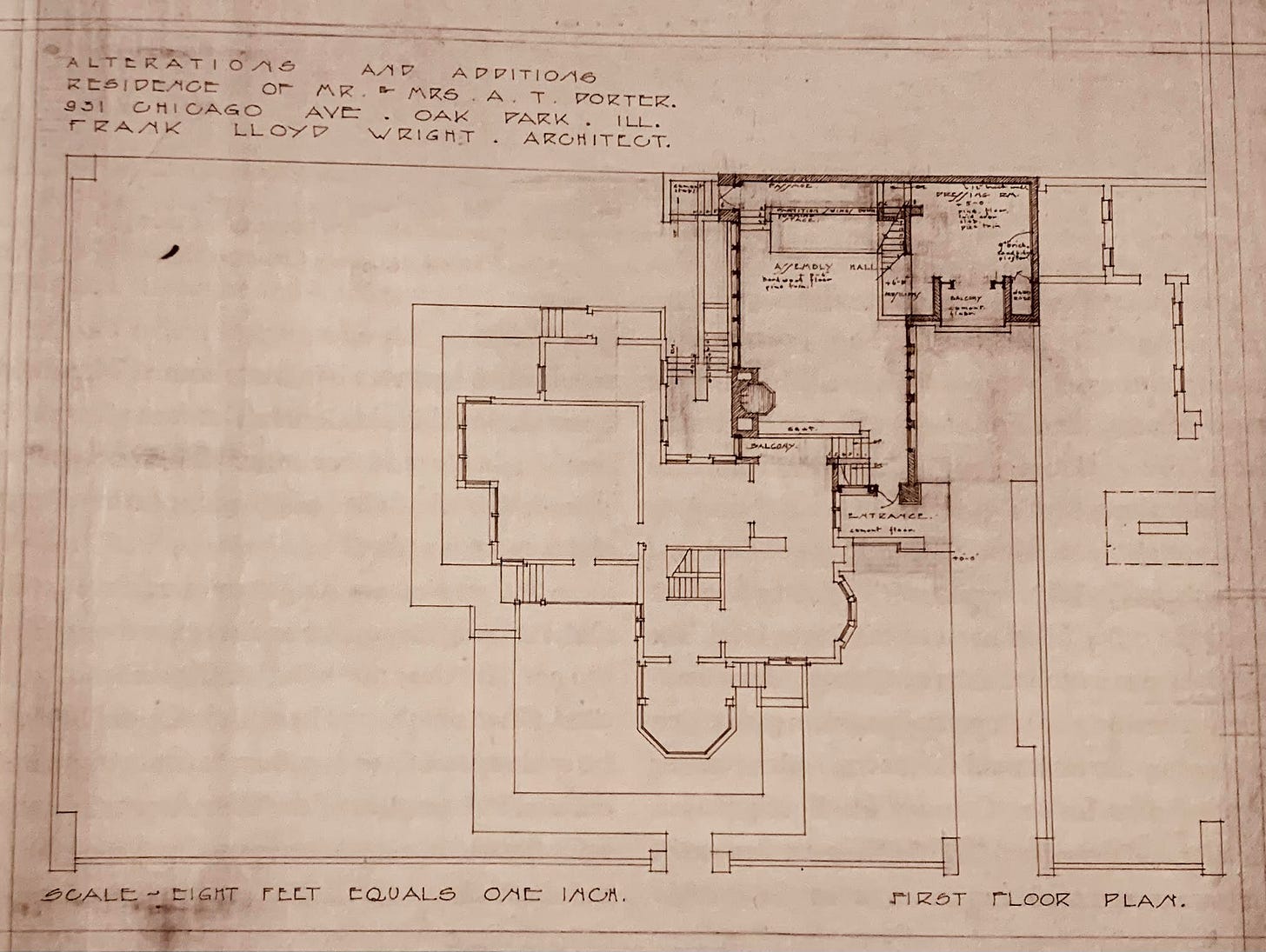

But let’s get back to the Home & Studio. At the beginning of 1919 not long after Catherine and her youngest child Llewellyn moved out Viennese architect R.M. Schindler occupied the studio unit rent free while his employer Frank Lloyd Wright was in Tokyo. He lived there his wife, Pauline Gibling, whom he had met at Jane Addam’s Hull House the same year. He was also in charge of finding other renters for the property as Alfred, who continued to live in the house with his new wife and children, supposedly “balked” at Wright’s demand for $170 in monthly rent (significantly more than appropriate for the western suburban market at the time) and gave notice he would vacate the unit in May of 1920. Schindler had difficulty finding people willing to pay the exorbitant price after MacArthur moved out. It was only after he convinced his boss to lower the rent that he was able to find new occupants for the Forest Avenue house, the studio unit, and the servant’s quarters. It was also during this time that Wright’s sister Jane and her husband Andrew Porter, who were living in the house next door with mother Anna Wright, asked the architect to enlarge the residence with a design that would’ve connected it to his former home. By October of 1920 the Porters abandoned the design plans and instead moved into Wright’s Heurtley House around the corner.

By the way, the discussion of all these MacArthurs should not be confused with Albert Chase McArthur, who briefly worked at Wright’s Studio for less than a year between March 1908 and January 1909. The son of Warren McArthur, a client who commissioned one of Wright’s “bootleg” houses on Chicago’s South Side, Albert later went on design the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, which is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Wright. But that’s a whole other story.

Finishing up with Alfred MacArthur, you think he might have been on bad terms with Wright after he was forced from the architect’s former home due to high rent. But their relationship continued for decades. Alfred even commissioned a design from his friend, but Mary MacArthur did not like it and in typical Wright fashion, he refused to change anything to meet his clients’ needs.

Albert M. Johnson, the president of the National Life Insurance Company in Chicago, was introduced to Wright through Alfred who worked there before becoming a banker. In 1924 Johnson hired the architect to create a tall office building for his organization. One of Wright’s most breathtaking projects, it was a 25-story glass fortress composed of four identical wings with sophisticated copper panels. Although Johnson was enthusiastic about Wright’s scheme for the North Michigan Avenue site, it was not enough to actually construct it. In the 1930s Alfred helped finance the Wright-designed home commissioned by their mutual friend Lloyd Lewis in Libertyville/Mettawa. It makes sense as some of Alfred’s family, including Telfer, had moved to the area around this time. In numerous letters Alfred pointed out Wright’s extravagance in spending and flaws in the design but he was still invited to the housewarming gala hosted by Wright and the Lewis family. Guests included Charles MacArthur and his wife Helen Hayes, Harpo Marx, and drama critic Alexander Woollcott, who declared that “just to be in a [Wright] house uplifts the heart and refreshes the spirit.” I’m not sure if Alfred would’ve agreed with that statement?