International Women's Day: Isabel Roberts

Isabel Roberts was many things. A pioneering woman in the field of architecture, she was an assistant office manager, art glass designer, a draftswoman, and trained architect. Although referred to as just Frank Lloyd Wright’s secretary until fairly recently, the employees who worked in his Oak Park studio as well as Wright’s own son remember Roberts as one of the draftspeople helping out with the production of architectural designs. When Wright closed down his office in 1909, she was one of the few employees left behind to finish his remaining projects alongside John Van Bergen.

Yet Isabel Roberts’ role and contributions have been greatly minimized over the last century by architectural historians and even Wright himself. The egocentric architect was always dismissive of giving credit to others, and unfortunately historians took Wright at his word when he once described Roberts as his bookkeeper and baby-sitter (she helped care for Wright’s six children on occasion). While Wright took classes part-time at University of Wisconsin-Madison for only two semesters and never received a degree, Roberts completed three years of formal architectural training under Emmanuel Louis Masqueray and Walter B. Chambers. She was one of the pupils at their atelier (or studio), the first of its kind in the U.S. to teach the practice of architecture based on the Ecole des Beaux Arts. She wasn’t just Wright’s baby-sitter but an architect in her own right (no pun attended) who deserves as much credit as the men employed at Wright’s studio who helped to create new design styles and techniques, later known as the Prairie School of Architecture, and went on to build their own successful careers.

Hired by Wright in late 1901 or early 1902 Roberts assisted Walter Burley Griffin with office duties but also did drafting and art glass design. When eighteen-year-old Barry Bryne started working in the Oak Park Studio in June of 1902, he noted just five employees: Griffin, Roberts, Cecil Bryan, Andrew Willatzen, and George Willis. Marion Mahony, Wright’s first employee and “right hand woman” for over a decade, had taken a temporary leave of absence while William Drummond had left for Richard E. Schmidt’s office before he returned to Wright part-time in 1903. When I used to give tours at Wright’s Home & Studio, the office space would be described to visitors as where “secretary” Roberts worked, sitting behind the desk in one of the room’s custom-designed cube chairs. But in actuality Roberts worked on art glass design up in the balcony alongside Marion Mahony and Wright’s sister Maginel.

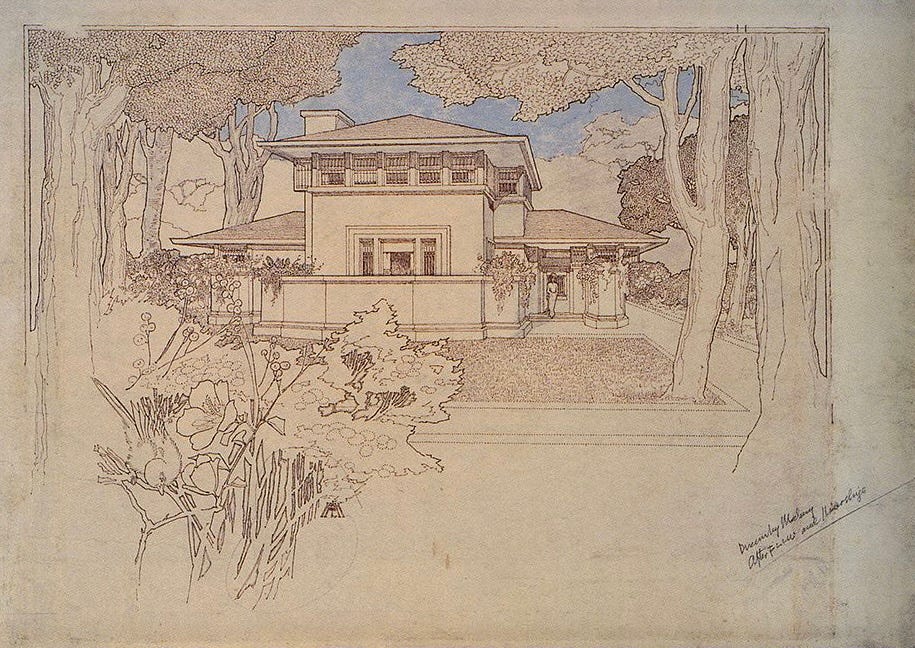

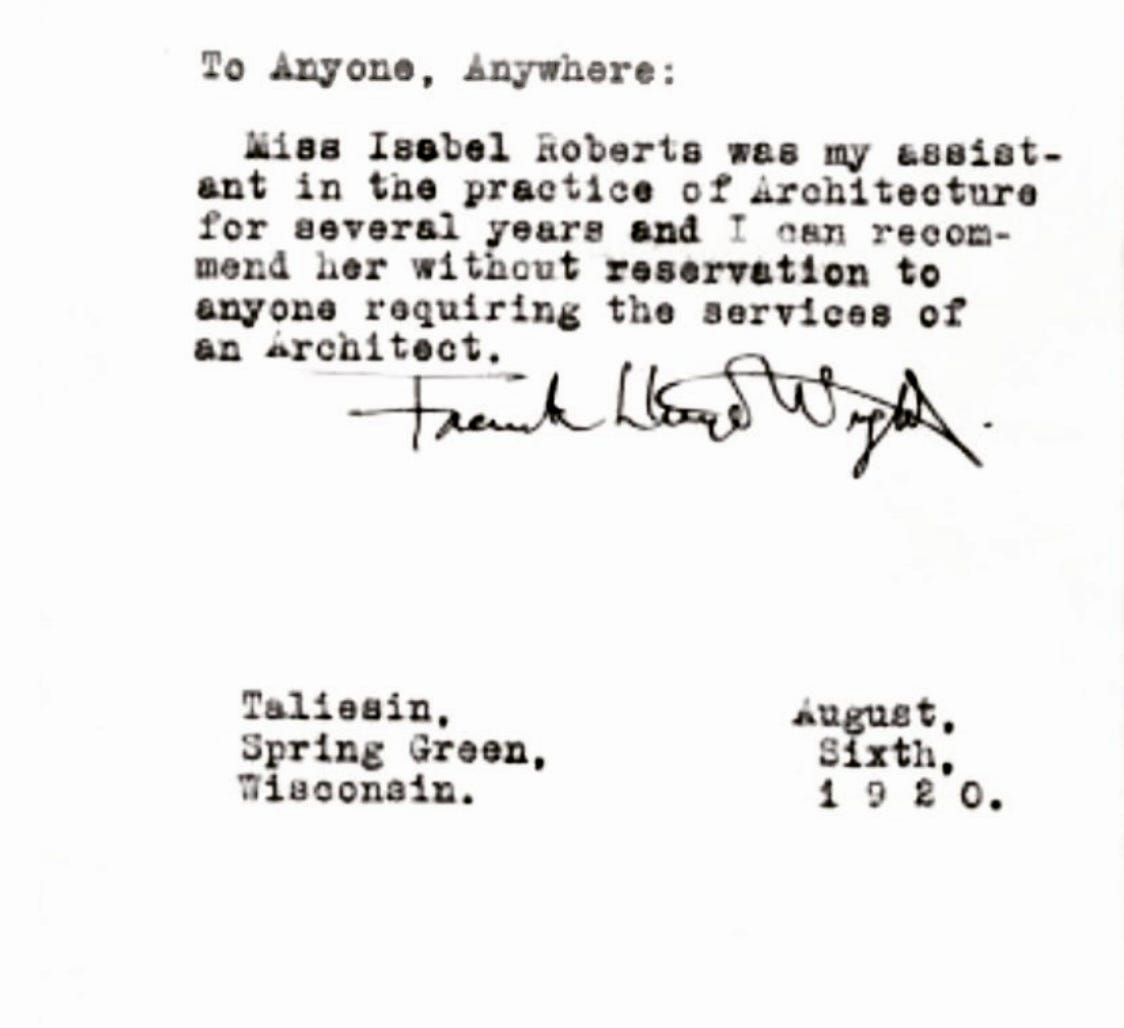

Roberts had grown up in South Bend, Indiana where her father worked as a deputy inspector for the city. It was this connection that led to Wright’s commission for the Kersey and Laura DeRhodes House (1906), not only a design that Roberts later claimed as having worked on but only came to the office through her friendship with Laura DeRhodes. During her AIA membership application fifteen years later in 1921, Roberts suggested she had completed this design while Wright himself confirmed her role in his office writing that “I can recommend her without reservation to anyone requiring the services of an Architect.” Roberts’ attempt at becoming a member of the American Institute of Architects proved unsuccessful, most likely due to her gender.

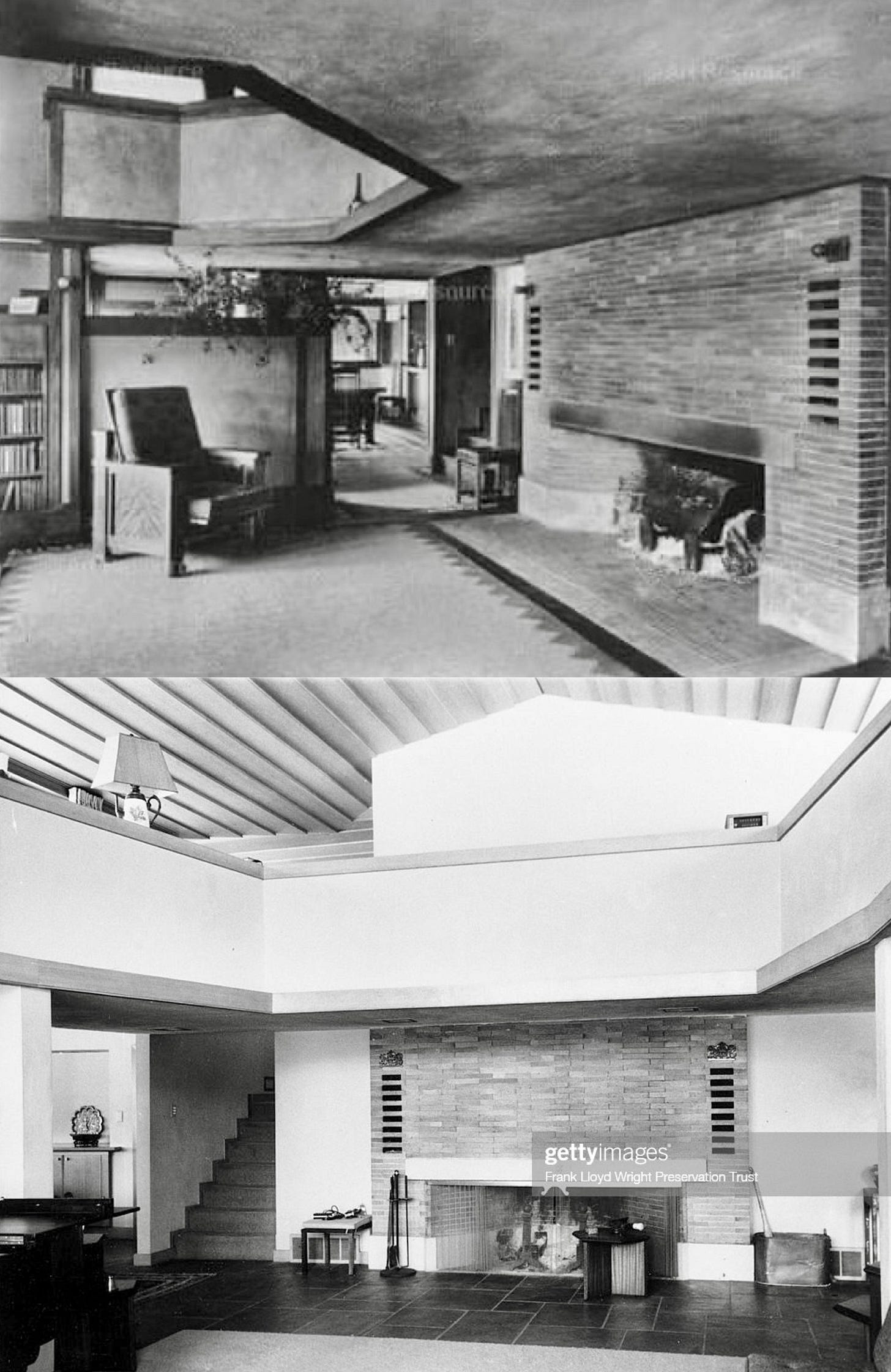

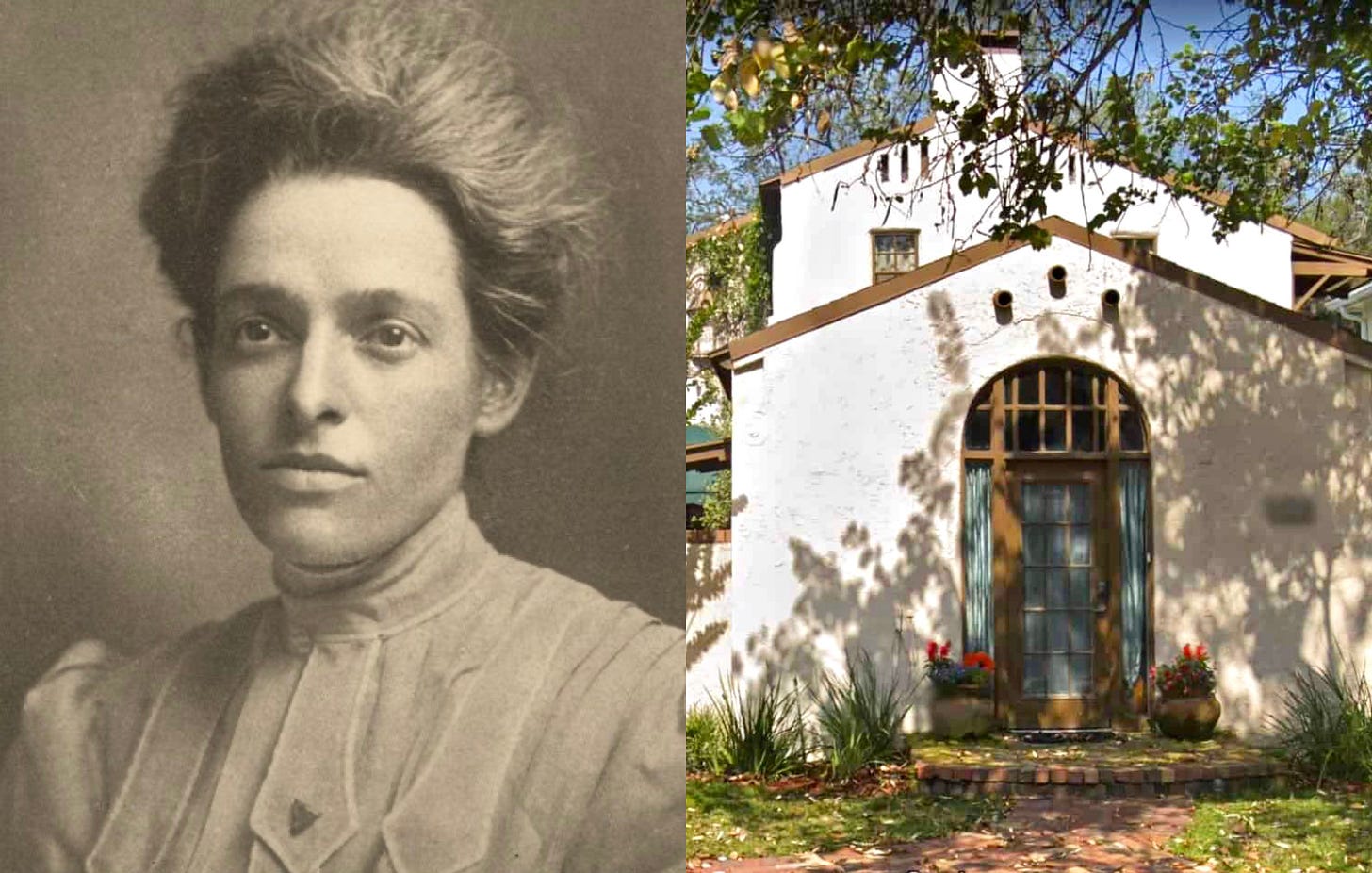

There is a public tendency to look at Wright’s work as strictly his own creation, standing in complete isolation with no regard to the collaborative atmosphere that existed in the Oak Park Studio. That is true of Isabel Roberts’ own residence (1908) in River Forest in which Roberts also insisted she had a hand in the design. It had been commissioned by her mother Mary who planned to live there with her two daughters. It makes sense that Isabel Roberts would have participated in its creation as many architects, Wright included, wanted to conceive the buildings they called home. Why should she be any different?

But some scholars have dismissed her claims saying that Roberts asked Wright to design something that looked similar to the dwelling he had proposed for developer Joshua G. Melson in Mason City a few years earlier. Whatever the truth, the Roberts family lived here for less than a decade, leaving for Florida just eight years after its construction. Another Wright employee, Harry Robinson, moved into the home around 1919. A full set of Wright-designed furniture was created for the home, which still exists just not in its original setting. Considered to be the country’s first split level residence, the home had many of the features typical of prairie style design, including continuous bands of windows and a massive Roman brick fireplace. Until recently a tree grew directly through the roof.

William Drummond, who worked on and off in the Oak Park Studio between 1899-1909, lived next door in a home of his own design. Drummond had bought the lot from Mary Roberts, probably for a decent price, and he later renovated Roberts’ home in the 1920s. Wright himself would remodel the home in the 1950s; marking the only time the architect personally updated one of his Prairie Style designs with later Usonian elements. Isabel Roberts wouldn’t recognize her own home. The entrance was completely redesigned while the exterior stucco was bricked over and the interior was updated with mahogany. The screened porch was enclosed.

According to the 1920 census Isabel Roberts was living with her mother Mary as well as her sister and brother-in-law Charlotte and John Somerville in St. Cloud, Florida. That same year Roberts opened an architectural firm in Orlando, Florida with her life partner Ida Ryan, one of first women to earn a master's degree in architecture from MIT. They had originally met in Oak Park. While operating her own office in Boston in 1906, Ida Ryan had a similar experience to Roberts when exclusionary policies of the local Society of Architects prevented her from gaining membership. The woman-led firm of Ryan and Roberts, which existed until 1945, gained commissions for a number of structures around Orlando including schools, residences, churches, apartment buildings, libraries, and a now-demolished band shell in Eola Park. They even designed a home and studio for themselves.

When Isabel Roberts died in 1955 at the age of 84, her death certificate listed her occupation as architect. Roberts was buried in Orlando’s Greenwood Cemetery in an unmarked grave alongside her mother and sister. Then in 2016 Isabel Roberts finally received the recognition she deserved during her lifetime when a proper marker was placed at her burial site. It honored her achievements as an architectural designer with Frank Lloyd Wright and Ida Ryan. Although she was never licensed nor had designed any significant project since the 1920s, Isabel Roberts was a trailblazer in the field of architecture. You wonder what she could have achieved if the prejudices against her gender, and possibly her sexuality, had never occurred. This monument is an important step in making sure this pioneering woman will never be forgotten.

Thanks so much to David Rifkind of Florida International University, Rexy Legaspi, John Dalles, and Lisa D. Schrenk of the University of Arizona whose research and writing made this article possible.