On the 168th anniversary of architect Louis Sullivan’s birth, I’m thinking of what it was like for the then 17-year-old when he first arrived in Chicago, the day before Thanksgiving in 1873. The city was still largely in ruins after the Great Fire, with miles of dirty and grey shanties, yet Sullivan saw potential in its reinvention. As he wrote in his autobiography: “There was stir, an energy that made [me] tingle to be in the game…THIS IS THE PLACE FOR ME!” Though he soon moved to Paris to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts for a year and work for renowned French architect Emile Vaudremer, Chicago still called out to him. It was “wild and magnificent,” a growing and innovative city with “intoxicating rawness” that would serve as the perfect place to experiment new ideas. However, Sullivan, only 19 years old, knew that he still had much to learn, despite his education and previous employment. So he began a little-known apprenticeship when he returned to Chicago in 1875.

During a short gig working at William LeBaron Jenney’s office years earlier, he first met John Edelmann, who hired Sullivan as a draftsman upon his return. In Paris, Sullivan wrote to his brother, Albert, about Edelmann: “You can make up your mind that my reputation will always be inferior to his.” Only a few years older, Edelmann became highly influential in shaping Sullivan’s architectural designs and philosophy, possibly even more so than during his time at the architectural firm of Frank Furness in Philadelphia. Or was Sullivan just following a path? I mean, you cannot discount Furness. Sullivan acknowledged his brief three to six-month stint with the architect as more significant than anything he ever learned in school. The ornamental style of Sullivan's first mentor evolved into a more organic, modern approach. However, in order for Sullivan to reach that point, he needed to continue learning from Edelmann.

Sullivan first learned the practice of polychromatic decoration with Furness, which would continue under Edelmann’s tutelage. Some of their artistic discussions were recorded in Sullivan’s “Lotus Club Notebook” (the club was formed by Sullivan and friends who met for intellectual and physical workouts at Lake Calumet), that had several pages of polychromed Gothic Revival designs and a number of essays written by Edelmann, including one on the history of decoration. But it was Edelmann’s concept of “suppressed function” that would serve as an inspiration for Sullivan’s well-known phrase “form follows function.” Many people mistakenly believe that this principle pertains solely to aesthetics. In reality, it relates to an architect's attempt to determine a building's purpose, which fundamentally influences the total design—particularly one that does not adhere to historical precedents.

In a 1924 issue of Western Architect, Irving Pond wrote: “John Edelmann influenced Louis Sullivan along other than purely philosophical lines…the sketches he made during those vividly described hours of converse between the two sunk deep into Louis’ consciousness and Louis’ ornament of the earlier period was little more than an interpretation of these emanations from John. [His] forms fit into some niche in Louis Sullivan’s nature and [Louis] made them his own.” Even a century later, preservationist Richard Nickel mistakenly attributed the demolition of an Edelmann building at 18th and Michigan to Sullivan, paving the way to the rediscovery of his work.

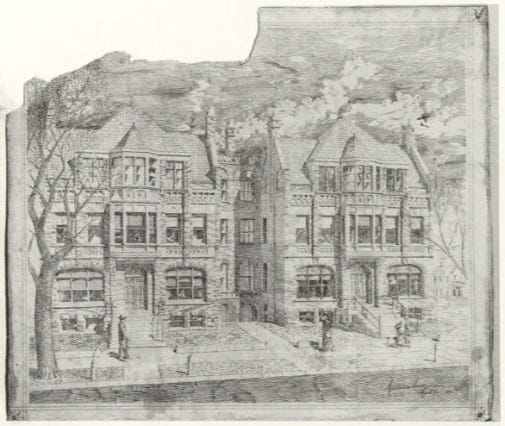

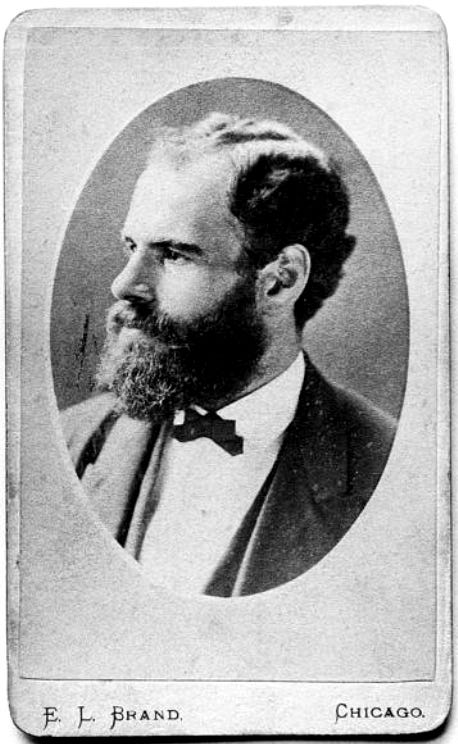

Edelmann, an unorthodox socialist-anarchist, assumed the role of Sullivan’s second mentor and introduced Sullivan to the man who’d become the final guide on his path towards greatness, Dankmar Adler. In the spring of 1880, Adler hired him and the two became collaborators. Sullivan was officially made a full business partner within the next few years. He was 26 years old. They had all teamed up previously on the design of the new Sinai Temple at the SW corner of 21st Street and Indiana Avenue in 1875, with exterior work done by Burling & Adler and interior design handled by the firm of Johnston & Edelmann. As Edelmann’s apprentice, Sullivan produced a Fresco-secco design scheme for the interior. Unfortunately, the building did not last long; it was demolished in 1912. Therefore, no photos exist to show Sullivan’s original design (it was remodeled by Adler & Sullivan 15 years later). But as you can see from the image below, the beginnings of his signature leafy ornament were slowly coming into place.

Dankmar Adler’s role as partner has been somewhat diminished over time, which is ironic when you think about it. He is the one who hired Sullivan in the first place. A decade older, Adler was already well-established as he’d been in the architecture field since the early 1860s. He was recognized as the true head of the firm (Frank Lloyd Wright often referred to him as ‘chief,’ writing that “he commanded the confidence of contractor and client alike…all worshiped him.”) who brought clients to their business, something that Sullivan, with his harsh personality, struggled to achieve when he ventured out on his own years later. As I searched through historic newspaper articles about them, Adler is consistently mentioned as “the main guy.” He served as president of the Western Association of Architects, secretary of the American Institute of Architects, and board member of Illinois’ examining and licensing of architects. Only his name was on the office door during those first years together. A glass panel etched with Adler and Sullivan side by side on their office’s entrance door in the Borden Block officially marked the team's partnership.

When Adler and Sullivan dissolved their union in 1895, they were the city’s second biggest architectural firm with over fifty draftsmen. An economic depression caused the separation, supposedly a rift as Adler needed money to support a family while Sullivan did not. Despite the break-up, the two men always had enormous respect for each other’s talents. They were extremely close in the early days. Sullivan would come weekly for dinners and participate in musical events at Adler’s home. Sullivan and Adler’s relationship with Edlemann continued as well. Employed by the firm until early 1885, it is said he assisted Adler and Sullivan as they worked on the Auditorium Building project from 1886 to 1889. Also, the Schlesinger & Mayer commission briefly revived the partnership by hiring Sullivan as architect and Adler as engineer in 1898.

In a 1924 issue of Inland Architect, architect Arthur Woltersdorf wrote about Adler: “Dankmar Adler, progressive, open minded, and far sighted as always, took Sullivan in and gave him scope that permitted the development of his genius.” Adler’s generous nature and enthusiasm for Sullivan should not be underestimated. I am sure all of us know plenty of talented people who have not found success. It all comes down to luck, knowing the right person, making connections, and being in the right place at the right time. Fortunately for architectural lovers, Louis Sullivan made the decision to return to live in Chicago after his studies overseas, and people like Edelmann and Adler gave him the inspiration and opportunities to flourish. Yet Sullivan could not reach that same level on his own. It’s almost like he always needed someone with a helping hand to lead the way.

Sullivan lost two important role models just a few months apart in the very same year of 1900. In April, Adler suffered a stroke and died aged 55, then in July, Edelmann - always plagued by ill health - died suddenly from a heart attack at the age of 47. It should come as no surprise that Sullivan suffered greatly at these losses. I don’t think he was ever the same. I’d imagine their guidance was why Sullivan struggled so much personally and professionally in the last decades of his life, as I wrote back in April. Edelmann encouraged Sullivan in architecture, drawing, and literary pursuits. He gave his pupil the confidence to experiment and develop his own architectural forms. Adler brought clients and stability to Sullivan, who grappled to regain that again after he lost his former business partner.

Like Furness and Edelmann, the majority of Sullivan’s work has been torn down, but 21 structures still stand in the city of Chicago, serving as a significant part of his (and Alder’s) architectural legacy, and to some degree, the architects that came before him.

SOURCES

Donald Egbert and Paul Sprague, "In Search of John Edelmann: Architect and Anarchist," AIA Journal (Feb. 1966), 35-41.

Charles E. Gregersen, Louis Sullivan and His Mentor, John Herman Edelmann, Architect (2013).

William O. Peterson, “Adler: The Rabbi's Son Who Designed the Auditorium Theatre,” Chicago Jewish Historical Society (April 1990).

Tim Samuelson, Louis Sullivan’s Idea (2021).

Louis Sullivan, The Autobiography of an Idea (1924).

John Vinci and Ward Miller, The Complete Architecture of Alder & Sullivan, (2010).

Lauren S. Weingarden, Louis H. Sullivan and a 19th-Century Poetics of Naturalized Architecture (2017).

Very informative post. Thank you.

Here's my favorite quotation from Sullivan that he said when he got off the train in Chicago from Philadelphia “A crude extravaganza: An intoxicating rawness: A sense of big things to be done. For ‘Big’ was the word. ‘Biggest’ was preferred and ‘the biggest in the world’ was the braggart phrase on every tongue.”

He, with Adler, took it to even bigger heights.