“And I say that all we see and feel and know, without and within us, is one mighty poem of striving, one vast and subtle tragedy. That to remain unperturbed and serene within this turbulent and drifting flow of hope and sorrow, light and darkness, is the uttermost position and fact attainable to the soul…”

-Louis Sullivan

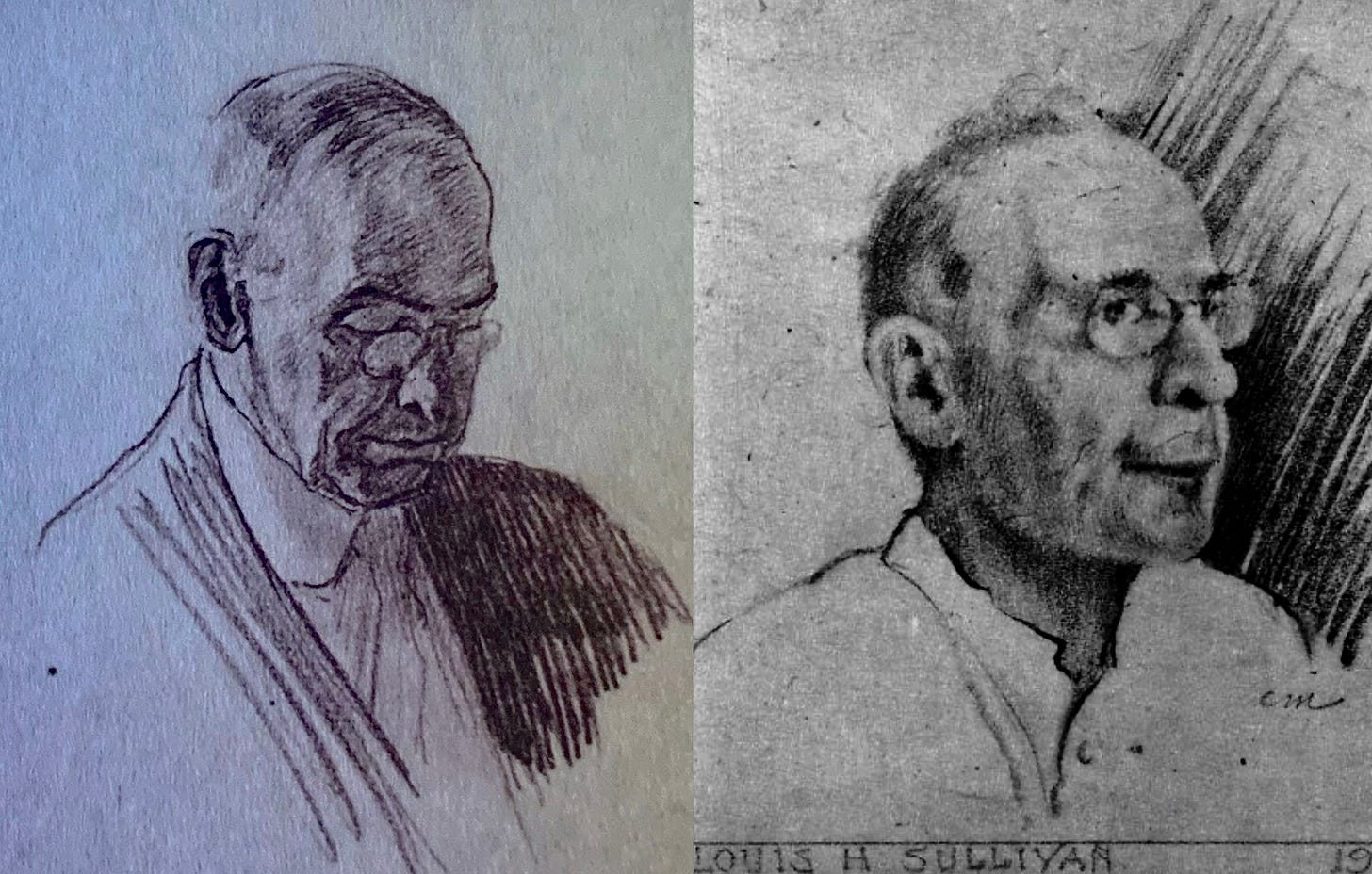

This past Sunday marked the 100th anniversary of Louis Sullivan’s death at a hotel on the South Side of Chicago. The architect has been called the “father of modernism” and viewed as the guiding force behind what became the Prairie School movement, yet he suffered a 20-year decline and died almost forgotten by the public, except for his disciples who remained fully loyal to him and his legacy until the very end. Muralist Oskar Gross recalled the tragic final years of the architect, who was a shell of his former self and without steady work: “I still have a memory that hurts me down to the core…when I saw him once…touching me for a quarter on Michigan Boulevard.” Sullivan managed to get by with these handouts, including from his best known pupil, Frank Lloyd Wright, who was also struggling to make ends meet during this time.

How was it possible that this talented man’s professional career and personal life dwindled to such an extent? He had inspired so many people from all over the world, not just Wright who famously called him Lieber-Meister (beloved master), but also others like Richard Neutra, who later stated in a 1969 interview with Inland Architect that he moved from his native Austria to Chicago because of Sullivan’s genius.

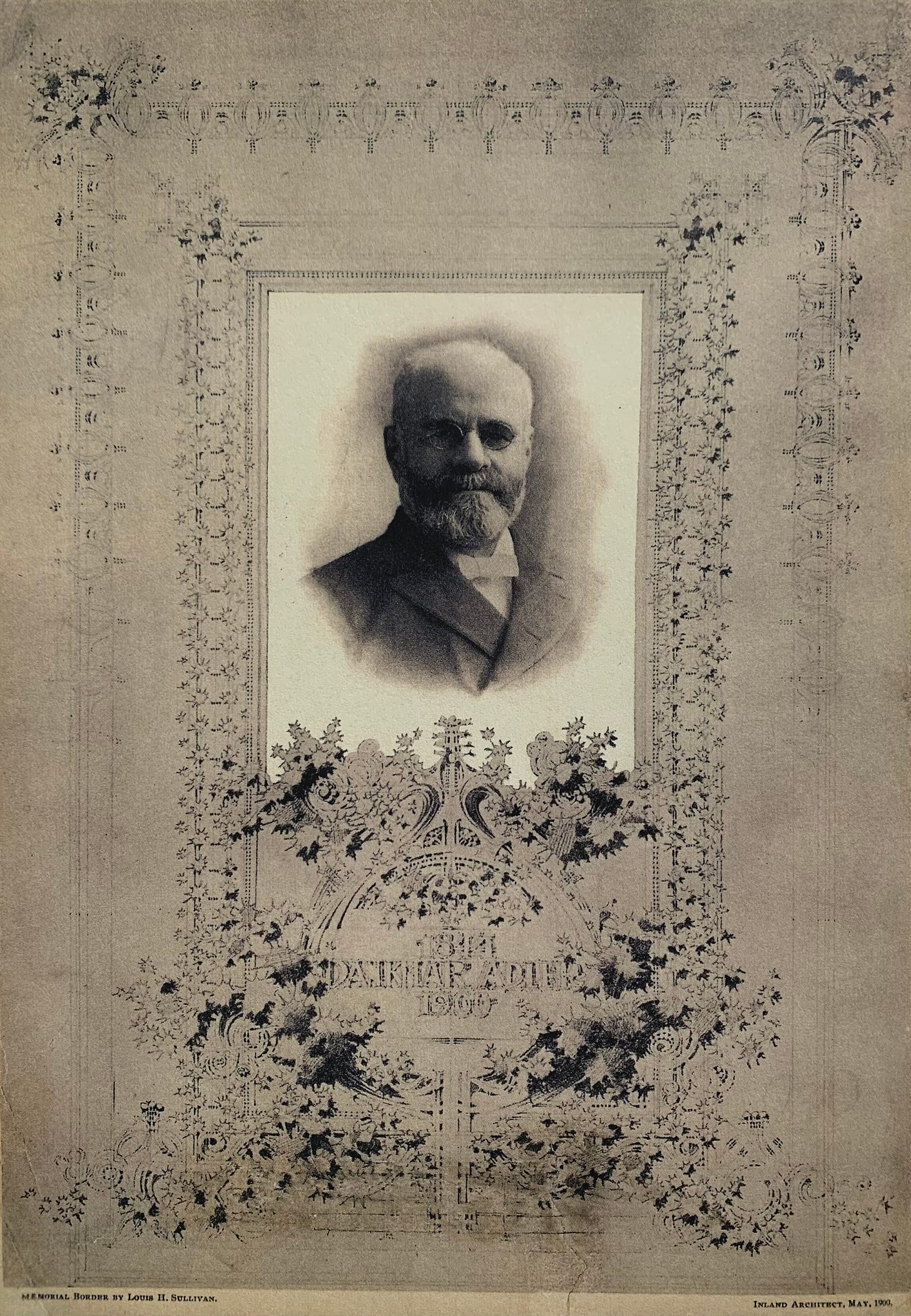

Like Wright, Sullivan was arrogant (and lacked Wright’s famous charm) and had a strong commitment to his architectural convictions, refusing to conform to trends or clients’ wishes. Sullivan’s assistant, George Elmslie, recalled that he lost many jobs because he would not compromise, which ultimately led to the decline of his architectural practice. Alcoholism was another factor in why Sullivan’s career was never the same after his breakup with his partner, Dankmar Adler, in July 1895. They had worked together for sixteen years, yet the two couldn’t stay apart, as both men contributed to each other’s solo projects. It was Adler’s connections that led to one of Sullivan’s most regarded works, the Schlesinger & Mayer Store (1899), where the two former partners revived their working relationship. But it wasn’t to be. Adler suddenly died at the age of 55 in April 1900.

Though extremely close to his only brother, Albert, Sullivan quarreled with him in 1896 and the siblings would never speak again. Historian Willard Connely believes that this is when Sullivan’s drinking became out-of-control, an addiction which would last for over twenty years until he completely gave up alcohol in 1920. Even when he had dedicated clients like Carl K. Bennett who offered him a number of commissions, Sullivan was sick, distracted, and moody. He had become his own worst enemy.

Wright himself was said to express shock at Sullivan’s bad habits of smoking, drinking, and paying for prostitutes, which dated back to his days living in Paris. Sullivan’s depression and vices had compromised not only his genius but also his ability to work with others. After all, architects do not work for themselves. They need patrons. Elmslie confided in a letter to his architectural partner, William G. Purcell, writing “Louis can’t get off his high horse and never will, I suppose. He doesn’t know how to handle people.” Edith Gutterson, who worked at Hull House, occasionally had lunch with him at the Tip Top Inn. She remembered his gentleness but also the “fire (that) would flash from” his eyes when roused. His alcohol addictions, and relieving his hangovers with the toxic Bromo-Seltzer, worsened his already fragile health.

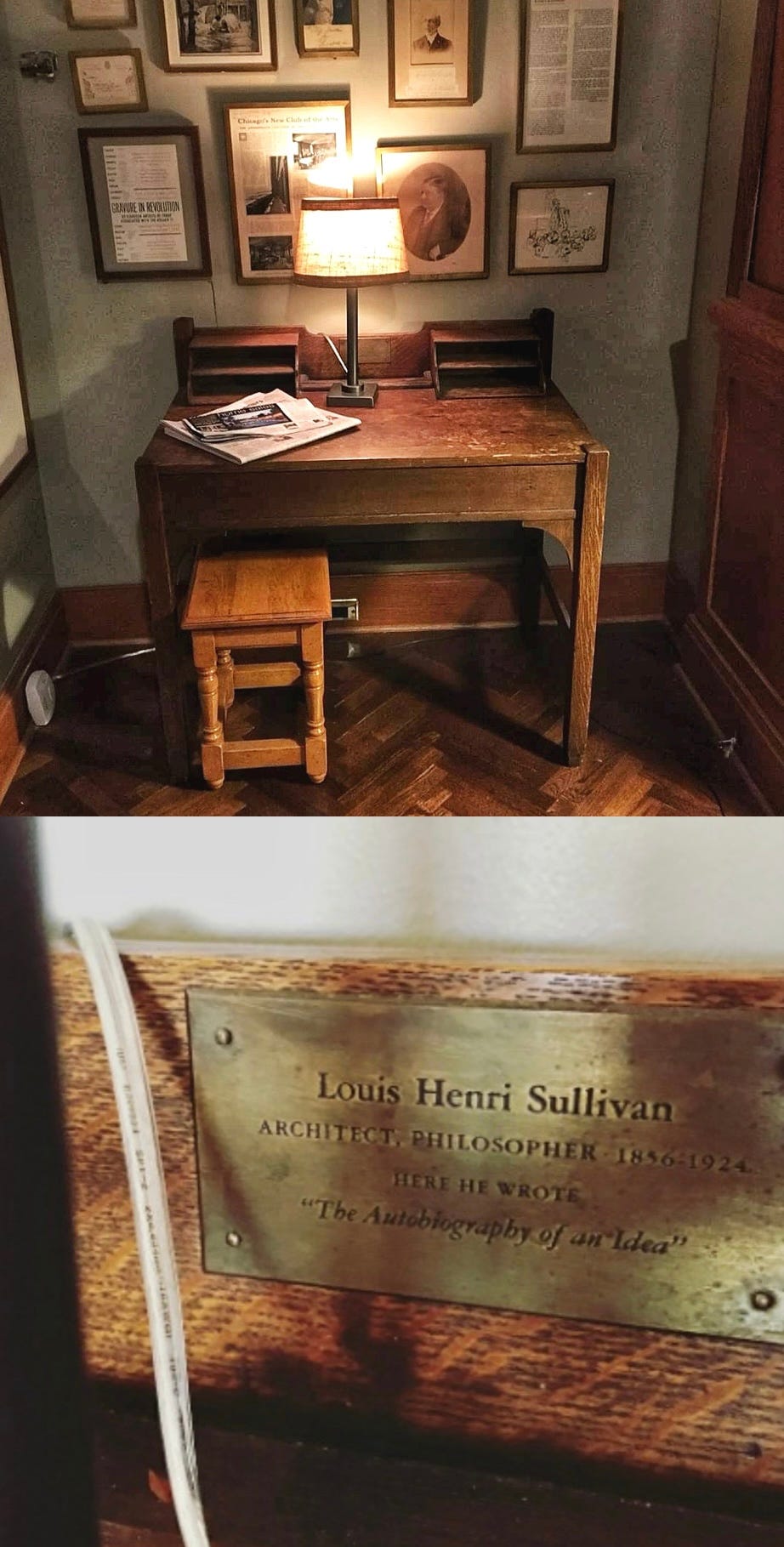

What happened to Sullivan in his last years was sad. However, it’s even more depressing that his final project was not a building. Instead, it was ornamental designs for sheet-metal pads placed under stoves and space heaters. This shows how desperate Sullivan was for work and money, yet he wasn’t too proud to take whatever he could get. Nearly penniless and without steady work, he was forced to move out of the Auditorium Building where had an office inside its tower since 1889. The American Terra Cotta Company let him work in their building at no cost. The Cliff Dwellers Club, then located at the top of Orchestra Hall, gave him free meals and provided a writing desk where he would write until 3 in the morning. It is still there.

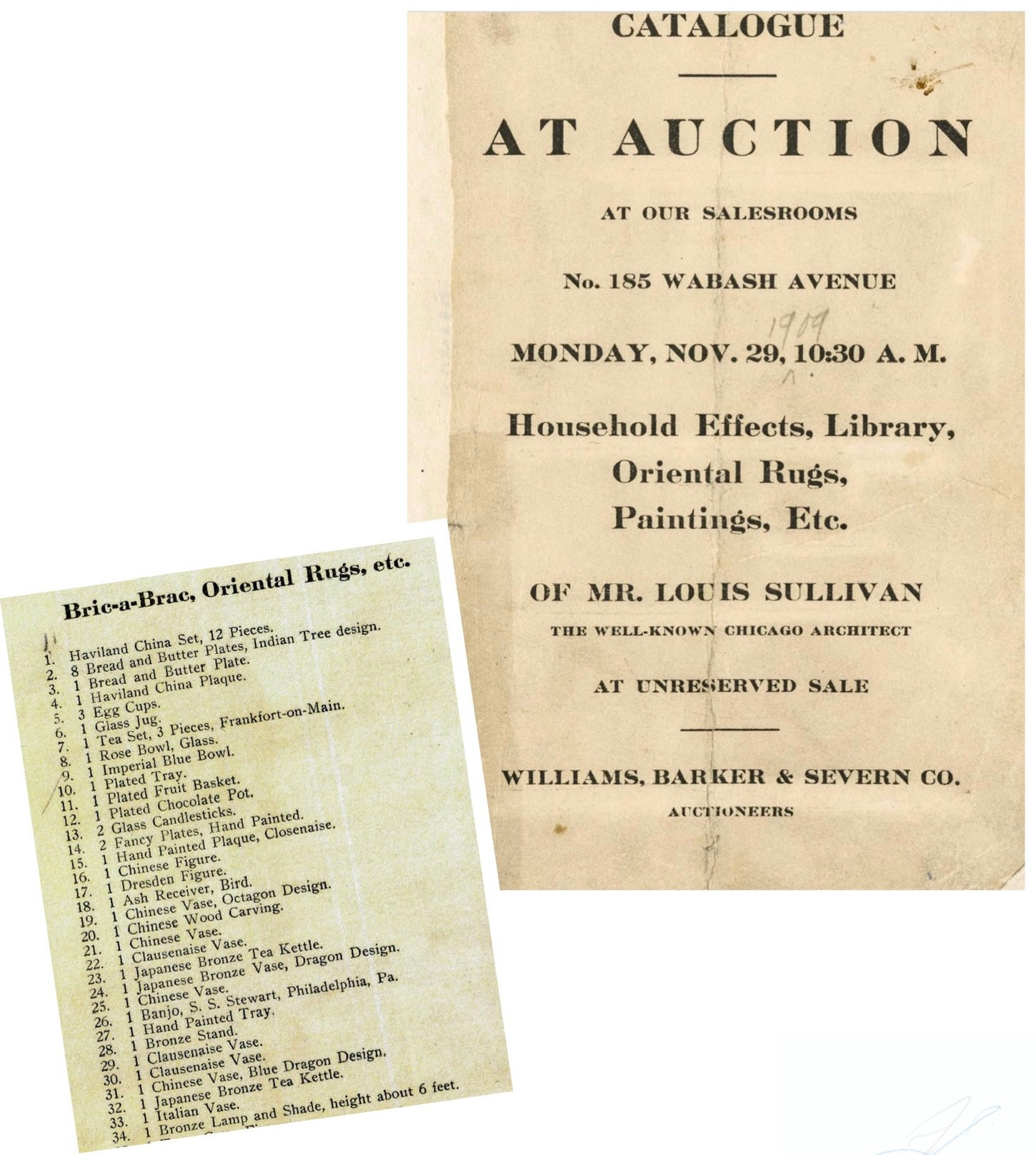

In desperation, Sullivan was forced to sell almost everything he owned, including his entire art and literary collection. In a letter to client Carl K. Bennett, he wrote, “I am…selling out at auction all my household effects: books, bric-a-brac, rugs, furniture, everything in the last desperate endeavor to raise money.” The auction took place on Wabash Avenue, not far from Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building, on November 29th & 30th 1909. Clients like Bennett and Henry Babson purchased some of Sullivan’s possessions. It turned out to be a disappointment. Sullivan expected to net between $2000-$2500, but instead only received $1100. He later went through what was left of his architectural library, which included monographs and copper plate engravings, to arrange private sales in hopes of making more money than at the auction. He also planned to sell an old master to the Art Institute of Chicago for $1000.

Sullivan was growing increasingly isolated during this time, greatly dependent on his doctor (I’ll get to him in a minute), who advised his patient that all his problems were due to a flaw of character and a “lack of kindly feeling toward my fellow men.” Suffering from “insomnia, nervous dyspepsia (indigestion), poverty, worry,” he wrote in another letter to Bennett that (he) “had to let Elmslie go. I was driven before it as a whirlwind drives in to the very verge of insanity or suicide, or nervous collapse.” Still Sullivan was hoping to break “the bonds of the prison of self” and change for the better. “I should have 20 to 30 years of hard work in me yet.” Again, that was not to be.

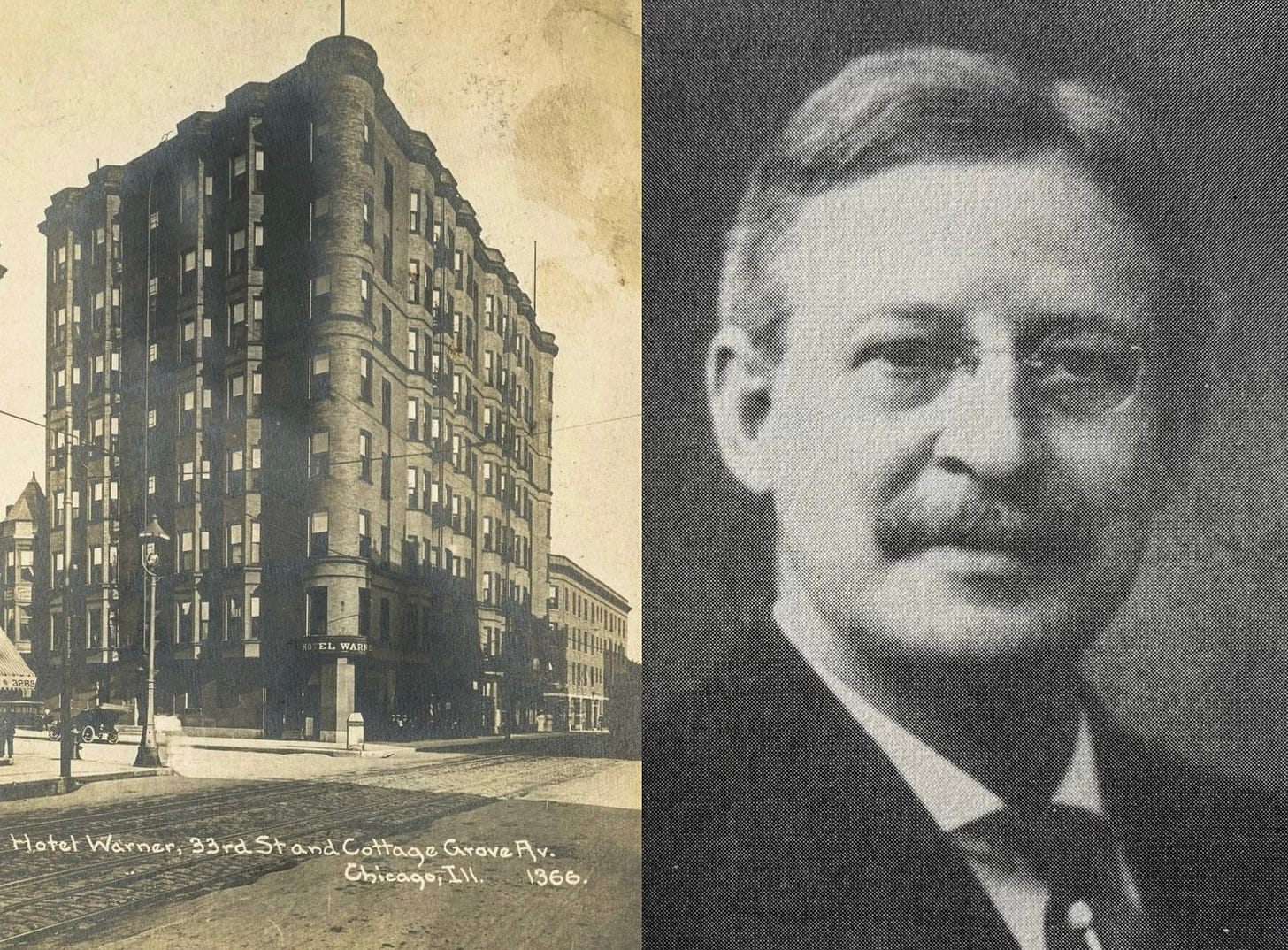

For almost fifteen years, Sullivan lived in a $9-a-week single room inside the Hotel Warner & Annex at 33rd & Cottage Grove. Permanent rates were offered at a discount for residents like Sullivan, who’d been looking for cheaper lodging since he left the Lessing Annex Building at Broadway & Surf. His regular physician from 1909 to 1923 was Dr. George D. Arndt, whom he knew from Elbert Hubbard’s Society of Philistines and had studied homeopathic medicine. From my own interpretation, Arndt did not seem to be the best medical professional to take Sullivan’s health seriously, especially when most scientists today view homeopathic treatment as a sham. Historian Willard Connely mentions a Doctor Curtis (possibly W. Pingree Curtis, who lived nearby at 3265 Cottage Grove Ave) and a nurse attending to Sullivan prior to his death in 1924, but it was far too late to save his life. He had difficultly breathing. Only with the assistance of others could he climb the Cliff Dwellers Club stair, where he kept a desk and received his mail. By 1924, he had an enlarged heart and a useless arm and hand, which had once created so many incredible drawings and plans.

Frank Lloyd Wright had been estranged from his mentor for more than twenty years, reconciling with him in 1918. Sullivan wrote a letter to Wright, begging for money as he was “living in hell.” Wright referred to one of the prostitutes that provided much needed companionship to Sullivan during his solitude as “the little henna haired milliner.” Tim Samuelson speculates that it was her death in the summer of 1923 that led to his own the next year. In An Autobiography, Wright recalled his last interaction with the Lieber-Meister: “He begged me to stay and died the day after I had left him with nothing left in the world, except a beautiful old daguerreotype of himself, aged 9, with his mother and brother.” He died from kidney disease and myocarditis with the first published copy of The Autobiography of an Idea still in his hands.

What was left of Sullivan’s possessions, which altogether fit in a single box, were packed away by his nurse and the Hotel Warner manager. Architect N. Max Dunning brought the box to Albert Sheffield of the American Terra Cotta Company. The $200 in Sullivan’s bank account, which had been put there by his friends, was used to pay for arrears at the hotel and other small bills. Dunning ripped up IOUs he found.

During Sullivan’s funeral at Graceland Cemetery in April of 1924, Richard Neutra, who had settled in Chicago about six months earlier, finally met Wright for the first time. He thought Wright “looked ill at ease in front of a lot of hometown adversaries.” When Neutra acquired if he could help Wright with his commissions, Wright replied, sounding a lot like his mentor Sullivan, that “I don’t have any work, you know. A modern architect can’t have any work to speak of in this country.”

According to the May 1924 issue of The Western Architect, Reverend Ogden Vogt of the Wellington Avenue Congregational Church conducted the services in the cemetery chapel. Dankmar’s son, Sidney Adler, George Elmslie, and Albert Sheffield were some of the pall bearers. Other architects in attendance included the ever-loyal N. Max Dunning as well as Thomas E. Tallmadge (I’ll get to him in a minute).

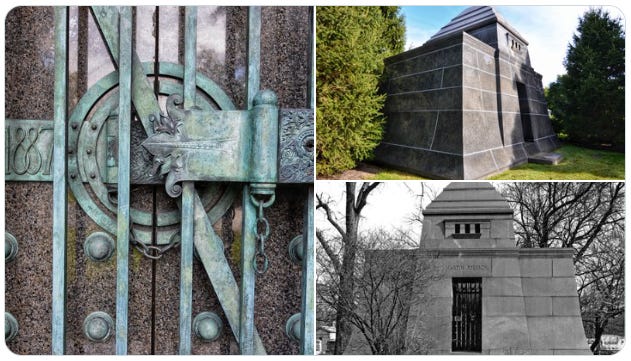

Graceland Cemetery, with its landscape developed in the 1870s, is the final resting place to many wealthy Chicagoans, but what stands out more than anything is its connections to the Chicago School of Architecture. Not only patrons such as John Glessner, Lucius Fisher, and Lambert Tree but there are many significant architects buried here besides Sullivan: Daniel Burnham, Howard Van Doren Shaw, Marion Mahony Griffin, and Mies van der Rohe. Sullivan designed two tombs at Graceland: a truncated pyramid of polished black granite for Martin Ryerson and a limestone cube that combined Sullivan’s love for geometric mass and intricate leafy ornament for Ryerson’s partner, Henry Getty.

The devotion to Sullivan continued after his death as his friends raised money in 1928 for his unmarked grave, not far from Ryerson’s, that would “serve as a memorial to his greatness.” A joint committee, led by Thomas E. Tallmadge who coined the term “Chicago School,” agreed on several features of Sullivan’s headstone: it would be made of granite, the decoration would express Sullivan’s philosophy, there would be a summary of his life and achievements, and it would be paid for from private donations. Elmslie would create the final design of the monument, yet no explanation was ever given as to why his proposal was not used. Instead, Tallmadge’s design was chosen: a granite boulder with a bronze replica of a Sullivan design featuring a relief portrait of the architect in the center on one side followed by a brief biography carved on the back. The sides would resemble a symbolic skyscraper.

Elmslie did not want his name attached to the final design, as he stated in a letter to Tallmadge and seven other members of the committee: “I want it made clear that I did not, and could not with intimate knowledge, based on years of association of Sullivan’s philosophy and ideals, design the present structure.” So what had Elmslie proposed? His sketches depict a large monument in the form of a single vertical shaft with delicately carved plant forms and ornament carved on the top. Quotes directly taken from Sullivan’s writings would be inscribed on each side: “Form Follows Function” and “The Utterance of Life is a Song, the Symphony of Nature.” There was also supposed to be a bronze portrait of the architect between the decorations and inscriptions. But what stands out is how imposing it would have been. Elmslie wanted it surrounded by a large grass and slate area with steps going up to it on all four sides.

The last twenty years of Sullivan were heartbreaking. Blow after blow as commissions dried up. He was publicly humiliated after selling almost all his possessions, sinking him further into despair. Willard Connely believes the architect’s fall had started much earlier, even before the dissolution of the Adler & Sullivan firm. 1891 to be exact. There was the death of John Wellborn Root, an architect who not only played a key role in the development of the modern American skyscraper but was also a pioneering modernist like Sullivan. Then you have the classical direction of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition that he feared would set America back in the wrong direction. And finally, the rejection of his first proposed set-back skyscraper, the Fraternity Temple. I bring this up here because they are all good theories. Sullivan was too ahead of his time, and we continually see what happens to artists who find their work rejected by the norm. Sullivan’s creativity was crushed, starting in the 1890s, and most likely messed with his spirit, sending him on a downward spiral in which he never truly recovered. In the words of Wallace Rice, who read a tribute at Sullivan’s funeral services, Sullivan was “a commanding figure between originality and tradition…in all its forms.” He lost the battle, but his message will live on.

SOURCES:

Sullivan’s Idea by Tim Samuelson

The Prairie School Review

A website dedicated to Purcell & Elmslie: organica.org

Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture by Hugh Morrison

Louis Sullivan: The Shaping of American Architecture by Willard Connely

Thank you for commemorating Sullivan with such an informative and thoughtful post. It’s very sad that his brilliance and talent plummeted and he lived in misery for so many decades. It’s a sorry contrast to his initial enthusiasm and excitement that he brought to Chicago when he stepped off the train there for the first time. Too bad he’ll never know what joy and beauty he would bring to so many through his stunning designs and visionary thinking.

I look forward to your next post. Thanks again for this one.

Simply and beautifully written--thank you!