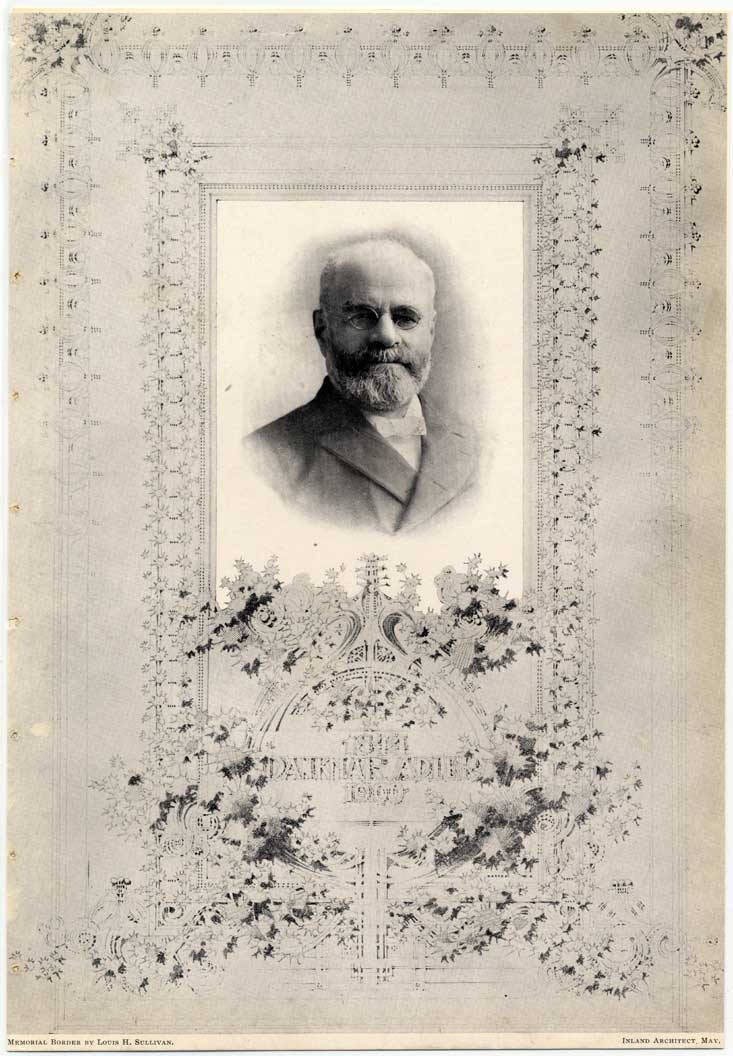

As your architectural obituary queen, I am here to remind you that this week marks the anniversaries of the deaths of one of Chicago’s greatest architectural partnerships. Louis Sullivan passed away on April 14, 1924, nearly a quarter-century after Dankmar Adler, who died on April 16, 1900. (Here is a nice little write-up, if you’re interested).

As I wrote back in September, Louis Sullivan often overshadows his colleague, who truly deserves the primary credit for their achievements. Sullivan was known as demanding, detached, and difficult. If he found success in the early part of his career it was mostly thanks to his then-partner, Dankmar Adler, who handled clients and business dealings. If you take a look at the floor plan of the Adler & Sullivan offices at the top of the Auditorium, it is plainly clear who was “the face” of the firm. Adler worked right next to the reception area, while Sullivan was tucked away in a far corner away from consultations. I believe their breakup in 1895, and Adler’s early death five years later at the age of 55, partially contributed to Sullivan's downfall, as he struggled to gain commissions while he worked as an independent architect.

In the story of Adler and Sullivan, the older, wiser, and more experienced partner appears to have been largely forgotten. In An Autobiography, Frank Lloyd Wright described his former mentor, whom he referred to as “my Big Chief,” as a figure who was revered and respected by everyone around him, “[Adler] commanded the confidence of contractor and client alike. His handling of both was masterful. He would pick up a contractor as a mastiff would pick up a cat - shake him and drop him.”

When examining the projects of Adler and Sullivan, it is not surprising that many of them stemmed from Adler’s connections within Chicago’s Jewish community. They designed synagogues, residences, and commercial buildings for the population, which grew from 100 residents in 1850 to over 80,000 by the 1890s. The Adlers were linked to one of the city’s earliest Jewish citizens, Abraham Kohn, who’d been living in the city since 1845 and served as City Clerk during Mayor John Wentworth’s administration.

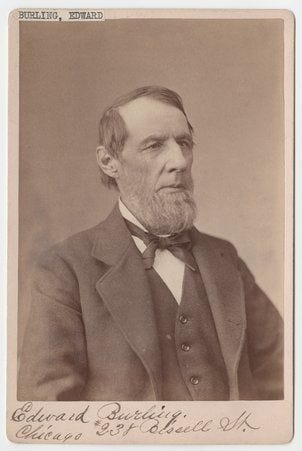

Beginning in 1861, Dankmar’s father, Liebman, became rabbi at the Kehilath Anshe Ma’ariv (KAM) synagogue, which was established by twenty men, including Abraham Kohn. Today it is Chicago’s oldest Jewish congregation. In June 1872, Dankmar Adler married Kohn’s daughter, Dila. It was barely a year after the Great Chicago Fire and his newly formed partnership with Edward J. Burling, one of the city’s pioneering architects who first arrived in Chicago in 1843. It is said that the pair “reconstructed four linear miles’ worth of streetscape in the single year after the fire, more than 100 buildings in all.” While most of it was rebuilding of lost structures and not much of Burling’s work survives (one exception is the Burling Row House District), it is worth noting that one commission during this time led to a long-lasting client relationship.

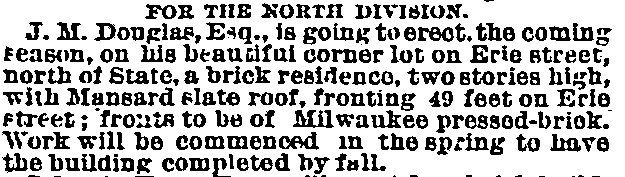

Adler was partners with Burling from 1871 until 1878, then he started his own firm the following year, which was also the same year he hired a young Louis Sullivan. Interestingly, the newspaper archives reveal what turned out to be an important project that Adler worked on independently in 1873 while he was still with Burling. But first, let me tell you a little bit about John M. Douglas (sometimes spelled as Douglass, depending on the source). John practiced law in Springfield and Galena before relocating to Chicago in 1855. Given the timeline, he worked alongside fellow attorney Abraham Lincoln. As legal counsel for the Illinois Central Railroad, he eventually became its director from 1861-1872, and then again from 1875-76. He married Amanda Marshall, with whom he had three children: Helen, Anna, and John.

In the 1860s, it was reported that he owned real estate valued at $100,000 (or almost $4 million today), including the NE section of LaSalle and Monroe. According to my research, the Douglas family lived at 297 Erie Street (now 8 East Erie), beginning around 1867, if not earlier. It was described as an elegant mansion in the book History of Chicago by Alfred Andreas. Unfortunately, the home, along with all its valuable contents including an impressive library, was lost in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Four months after the fire, a news article reported that there had been “a greater activity in rebuilding” due to mild weather, which included the Douglas home on the corner lot at Erie and State.

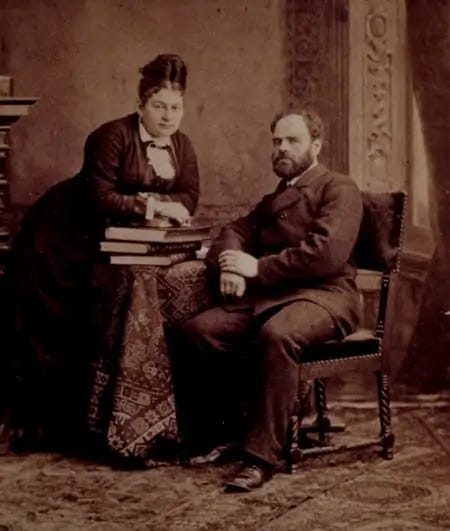

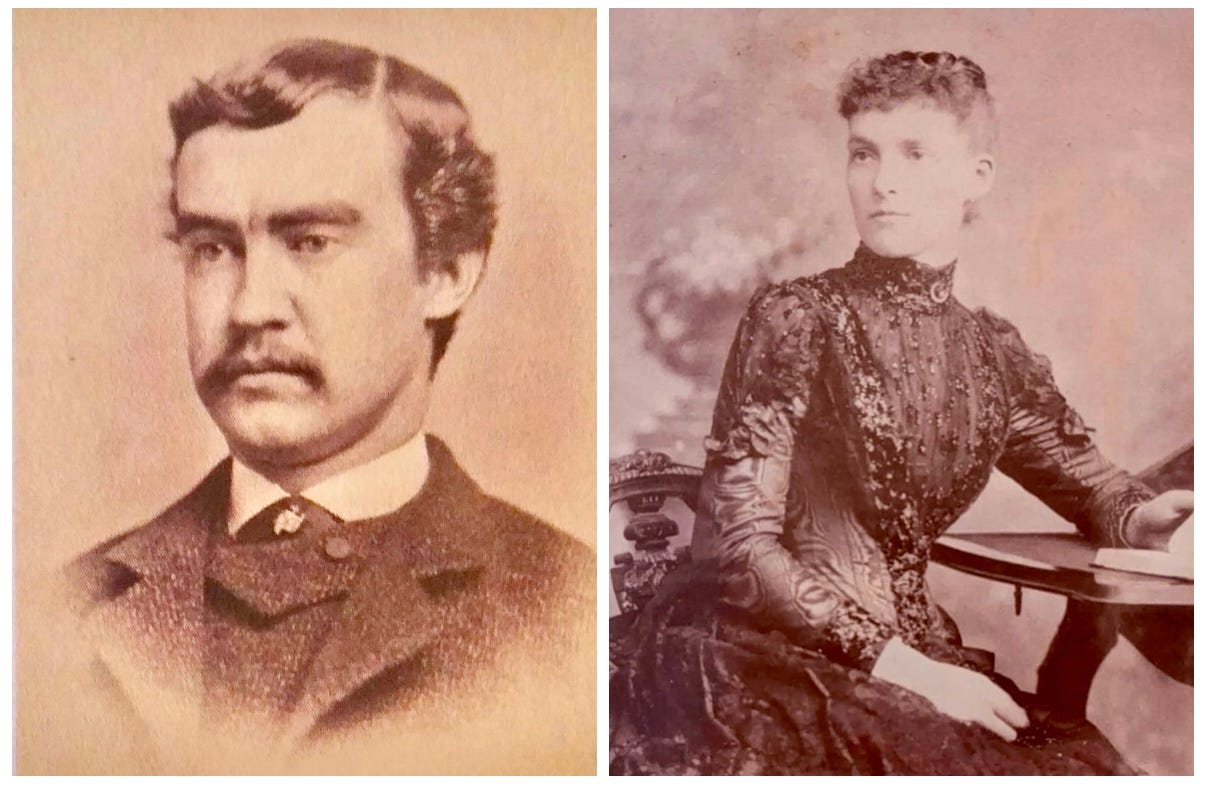

In October of 1872 the marriage of James Charnley to John’s daughter, Helen Douglas, was announced in the Chicago Daily Tribune. They had wed on Wednesday, October 23rd, at her parents’ newly completed home, a two-story Milwaukee brick design with mansard roof. Like his father-in-law, Charnley was a prominent member of society who made his living as a capitalist through investments in railroads and lumber businesses. His career began in 1866 when he opened a timber mill that was the first in the city to produce larger squares and joists. From 1881-84, he briefly partnered with John Douglas, along with John Jr., to form the James Charnley and Company. Three years earlier, a credit reporter surveyed that Charnley was a “close careful man with a good record,” but that his “main financial strength” came from John Douglas.

But what I find most intriguing about this story is what occurred less than a year after the wedding. In “The City in Brief” section of the June 2nd 1873 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, it was noted that “Mr. Adlar, the architect, has just finished plans for…Messrs. Douglas & Charnley, at the corner of Erie and State streets, two brown-stone front, first-class residences, basement and three stories; cost, $40,000…” It appears that the structures were completed by August of the same year. The misspelling aside, here is definite proof that Dankmar Adler created what would be the first Charnley House (believe it or not, the couple lived at thirteen different addresses in the city).

Yet this information is somewhat confusing. Douglas rebuilt his home after the fire, and it appears to have been completed by October 1872. About eight months later, he, along with Charnley, hired Dankmar Adler to construct two additional houses at the same location. Or was it a different corner? It doesn’t make sense? I find myself delving deeper into the rabbit hole as I try to figure out the story behind these homes, which I hope to explore further at a later date. However, what’s particularly intriguing about this 1873 commission is that it addresses a question that has perplexed historians for decades: “How did the Charnleys come to know Louis Sullivan?” If you recall the significance of Adler in client relations, we cannot overlook the fact that he first collaborated with the Charnleys nearly twenty years before their renowned home was constructed, and long before Sullivan ever entered the picture. So here is another question to ask: “Has Adler been lost in the Charnley story?”

The first chapter of Richard Longstreth’s 2004 book is titled "The Elusive Charnley House,” which aptly captures the ongoing research related to the family and their architecturally significant residence. There so much that is unknown. However, some of the book’s information seems to contradict this new discovery: “In 1879, the couple (referring to the Charnleys) purchased one of three row houses built by Helen’s father at the NE corner of Erie and State streets just after the fire. Having paid $8,500 dollars for the three-story dwelling, they sold it to William Keep (who had connections to the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad Company) for $18,000 three years later in 1882.”

In the 1890 Chicago Blue Book, I found James Charnley and his wife listed at the 297 Erie address, the residence of his father-in-law, John M. Douglas, with their previous home that they had sold eight years earlier, 299 Erie, now belonging to the James A. Hutchinson family. I told you they moved around a lot.

I also found another mention of Burling, Adler’s partner at the time. In December 1874 a list of ladies who would receive guests for New Year’s and Christmas parties was published in the Chicago Daily Tribune and the Sunday Times. One of the private social events of the season was a German dance held at Mrs. Douglas’ residence at Erie and State on Tuesday, December 22nd where about seventy people, the leading members of the North Side, enjoyed her hospitality. Kinsley provided the supper and Frieberg performed music, while “Mr. Burling (who I assume was the architect) led the intricacies of the ‘German,’” in other words, he was in charge of leading the dance.

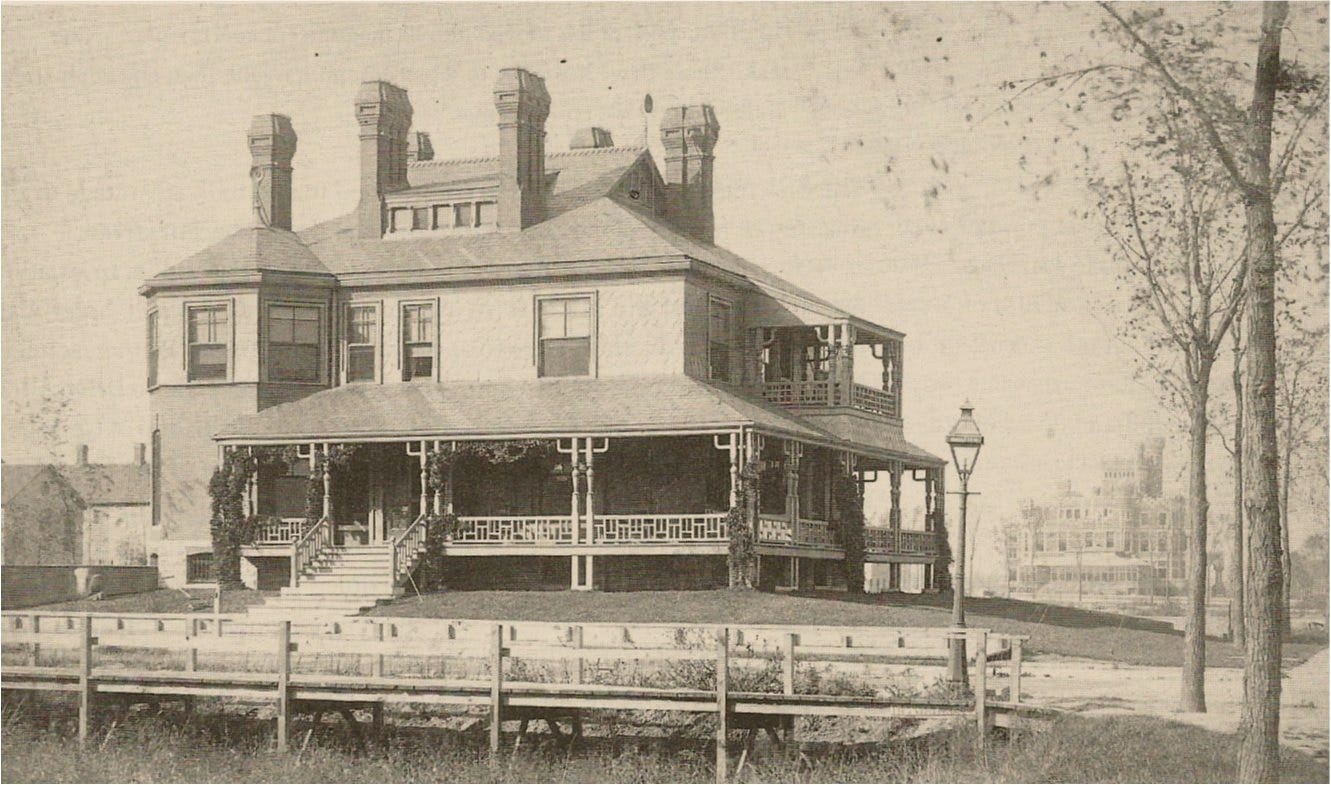

As I hope to understand the complete context surrounding Erie and State, the fact that Charnley commissioned Adler in 1873 also contradicts the prevailing belief among historians that the “first” architect-designed Charnley House was the lakefront Queen Anne-style residence at what is 1200 North Lake Shore, which was created by Burnham & Root in 1882. This home was located just a few blocks away from the Astor Street house by Adler & Sullivan that would be constructed a decade later.

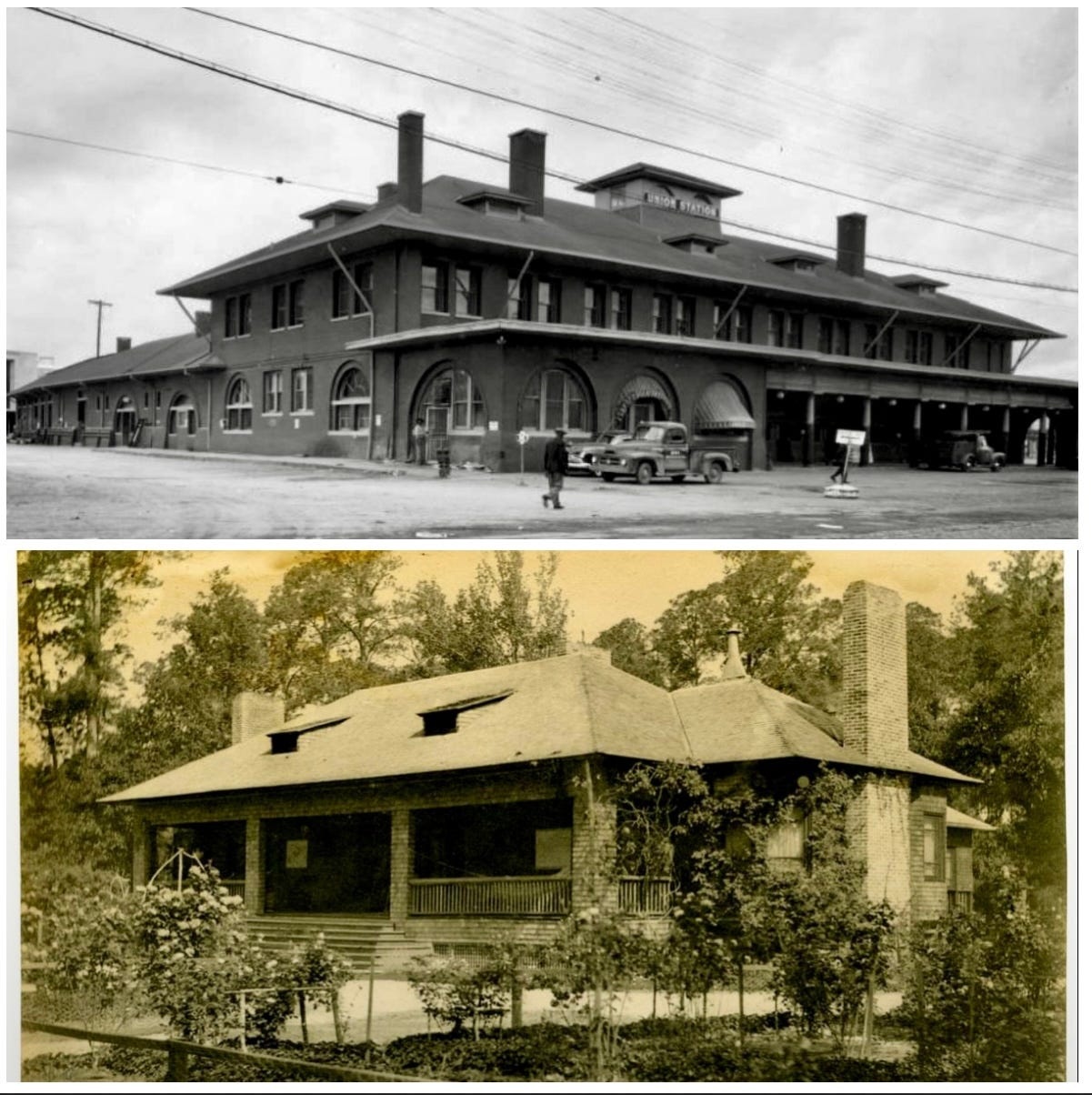

Let me return to the Illinois Central Railroad. Adler and Sullivan designed two commuter railway stations, located half a mile apart, for the company. The larger of the two, the 39th Street-Oakland Station, was constructed in 1886 and demolished in 1934. It was characterized by high-stepped gables and molded brick arch entrances. The other station, situated at 43rd Street, was built in 1888 and torn down in 1942; however, it was not as impressive in design, as it was largely overshadowed by its canopy. Many historians believe these commissions came through Sullivan’s brother, Albert, following his appointment as a superintendent of the Illinois Central Railroad in 1885. Although John Douglas had retired by this time, one must wonder if he still had any influence, especially when you consider his previous collaboration with Adler.

Adler & Sullivan also designed Illinois Central Railroad’s Union Station in New Orleans in 1891-92, which was also when the Charnleys hired them for two separate commissions simultaneously, their innovative home on Chicago’s Astor Street and a “winter” retreat in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. The impressive structure, clad in red pressed brick and stone, was the terminus of the route from its original destination in Chicago. With the rise of the automobile, the building was demolished in 1954.

As the general superintendent for the Illinois Central Railroad, Albert Sullivan could travel by private railroad car from Chicago to New Orleans, and continue on a spur line to Ocean Springs. I am sure that Helen Charnley, the daughter of the former president of the company, also had the same luxury. Traveling with Louis Sullivan, the Charnleys and the architect bought property together in East Beach, just steps from Biloxi Bay, and he designed what he called “two shacks” in March of 1890. The very next month, Albert Sullivan purchased adjoining land. But instead of building a retreat like his brother, Albert would "live for days at a time in his luxurious car of the Illinois Central Railroad parked on a spur a few hundred yards north of his land."

This is all so interesting to me as someone who has been writing about the Charnleys for almost ten years now. You might remember my three-part series published on Chicago Patterns. (Here is the first post, if you’re interested…and the second and third.)

Louis Sullivan and, of course, Frank Lloyd Wright tend to dominate the narrative surrounding the Charnley House. In regards to the ongoing controversy surrounding the home, there will always be lingering questions about the true architect behind its ground-breaking design. Wright referred to it as “the first modern home in America.” But after all this time, it appears that Adler’s significance has been greatly overlooked. Renowned for project management skills and strong client relationships, it is likely that he played a crucial role in bringing the Douglas and Charnley families into the fold. That first commission at Erie and State led to at least five additional projects. Like I said, I hope to explore this further in a future post, because when it comes to the Charnleys, there are always more parts of the story that need to be uncovered.

SOURCES:

The Charnley House: Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Making of Chicago’s Gold Coast by Richard Longstreth

Disposing of Modernity: The Archaeology of Garbage and Consumerism During Chicago's 1893 World's Fair by Rebecca Graff

Driehaus Museum: The Life and Work of Edward J. Burling

Mississippi Department of Archives & History

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum

Dankmar Adler: Courage, Architecture, and the American Dream

The Complete Architect of Adler & Sullivan by John Vinci, Ward Miller, Richard Nickel & Aaron Siskind

Just poking around online and I find this wonderful essay. So, so sad I did not know that Liebermeister passed on 4/14 and the Big Chief on 4/16...would have toasted them suitably on their respective necroversaries. Thanks for writing this. Nice to spotlight a real genius :)