Did you know that today only 23.3% of all American-based architects are women? Considering March is Women’s History Month when we commemorate the vital contributions made by women throughout U.S. history, I thought I’d highlight a pioneering Chicagoland woman architect who worked in this male-dominated field. Though she designed over 150 houses as an independent architect, Jean Wiersema Wehrheim’s career was cut short when she died at the age of 50 in September of 1977. Yet she left a lasting mark on a special community in the western suburbs.

Jean Wiersema, a native of Tennessee, graduated with a degree in architectural engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1948. Her father Harry, a civil engineer who worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), had grown up in suburban Berwyn so he might have inspired not only Jean’s career as an architect and engineer but also her decision to take up a job at the architectural firm of Keck & Keck in Chicago. She later married one of her co-workers, John Wehrheim, who had studied under Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology. After they wed in May of 1949, the couple worked for William DeKnatel, who had grown up in Chicago’s Hull House before becoming one of the first to join Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship. He later helped save Wright’s acclaimed Robie House when it was threatened with demolition twice in 1941 and 1957. Not sure how long they worked for DeKnatel, but in 1954 John Wehrheim started his own practice that specialized in large commercial buildings, while Jean focused on residential designs.

What brought the Wehrheims to the suburbs? Jean stated in a 1955 Chicago Tribune article that she came to Glen Ellyn to work for a contractor while her husband gave up his Loop job and opened an architectural office in Elmhurst with his partner Westing E. Pence. Where the two architects settled was no ordinary place.

In unincorporated Lombard, not far from Yorktown Shopping Center near Roosevelt and Meyer Roads is an interesting residential development. In 1947 a housing cooperative was established by Louis Shirky and a dozen members of the Church of the Brethen who bought the former Golterman dairy farm for $30,000. The bylaws were written by a Black attorney from Chicago, Ted Robinson, which proclaimed membership was “open to all persons of good will” including “Blacks, Orientals, Catholics, Jews, Buddhists, and Atheists.” This idea went against the typical residents living in postwar suburban DuPage County at the time, which was full of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ WASPs. Ted and his wife Leya, a Jewish social worker, along with their two daughters moved into the new community they helped create.

African Americans and other minorities had difficulties acquiring a home mortgage during the 1940s and 50s. York Center Cooperative was set up to help them purchase their own homes in an 80-acre oasis with no sidewalks or street lights built around a circular road called Rochdale. The aim of this new community was “to promote and develop good will, high moral values, wholesome cooperative activities and healthy civic spirit.” Yet Thurgood Marshall, then attorney for the NAACP, got involved when he suspected the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) was denying grants to this new interracial cooperative, claiming that “the unpaved roads created a blight situation.”

After numerous legal entanglements that involved both Harry S. Truman and the Illinois Supreme Court, the cooperative was ruled valid with ultimately seventy-two families (or 300 total people) residing there in 1964 (15% Black, 12% Asian, and some that identified as multiracial households). While it was legally dissolved in 2010, some of the homes built by the hands of early residents of York Center survive. Jean Wehrheim designed and/or supervised construction of at least eight residences in this tight-knit, rural community from the 1950s through the 1970s.

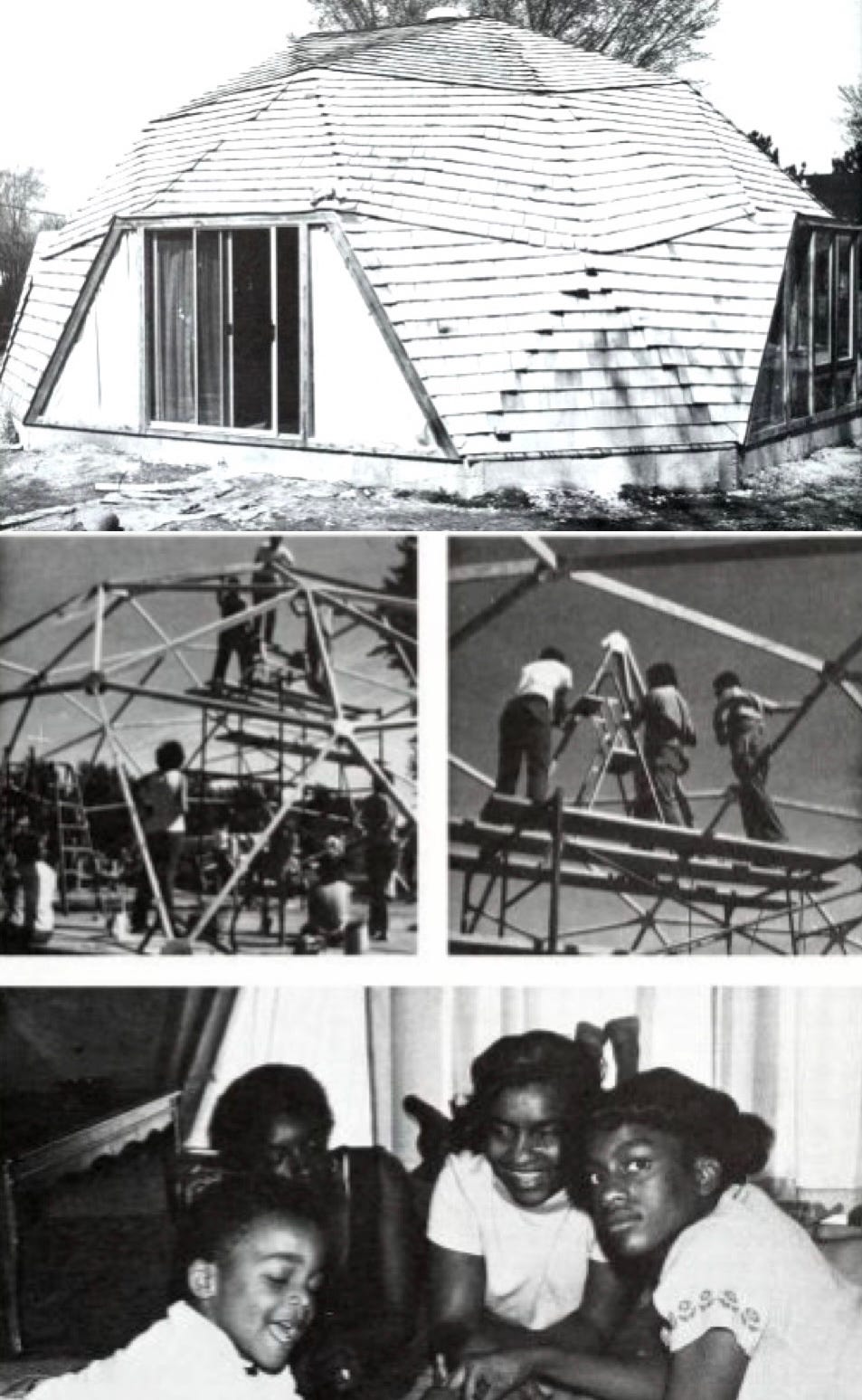

Following the geodesic dome principles devised by Buckminster Fuller, Jean created a new home for the Herrings, an African-American family from Chicago who moved into the cooperative in 1974. Over fifty members raised the basic structure with hubs made of molded fiberglass and sheet metal within one day. A free-standing core in the center of the house stored a heating unit, while pie-shaped rooms had views of the soaring dome roof. Sadly this unique abode on Luther Avenue no longer exists.

Jean even built her own passive solar home in the cooperative with her husband John; with both of them pouring the cement foundation and laying the roof shingles. Jean specialized in this type of design, probably learned from her mentor George Fred Keck, which utilized the site to take advantage of natural energy to heat or cool the home. A 52-ft-long wall of glass on its southern side along with overhangs kept the building warm in winter and cool in summer. It cost a little over $9000 for the Wehrheims to construct their new flat-roofed home, exactly half the price if the couple had hired a company to complete the task.

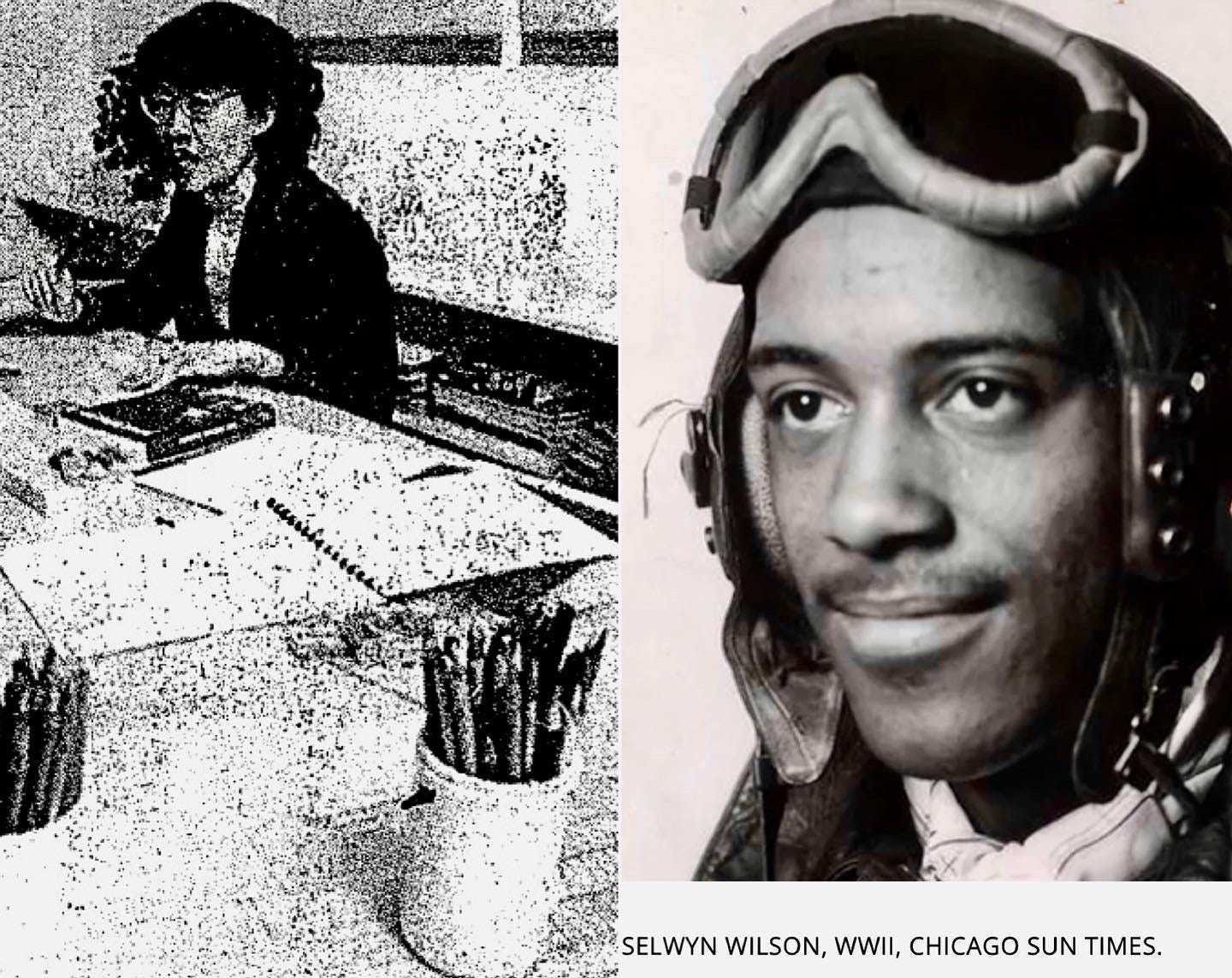

Jean expressed her frustration as a woman architect with contractors not taking her seriously and her inability to command the same fees as her male colleagues. Before a separate wing was added in 1966 so Jean could have her own office and workshop, she drew plans at a table in the corner of the kitchen after the children had gone to bed. One of Jean’s two drafting assistants was her neighbor, Mrs. Richard Roberts, who taught home design at a nearby high school. Another one of Jean’s neighbors was Selwyn Wilson, a Tuskegee Airman, who moved here in 1952.

It’s worth noting that Jean’s younger brother, Harry Jr., discussed in a 2009 article that their parents Harry and Ethyl were both members of the NAACP who sent their children to an interracial day camp while they lived in Knoxville. Was this the catalyst behind Jean’s decision to live and work in the York Center Cooperative? We’ll never know for sure. It’s also interesting that her father was one of the survivors of the M.E. Norman, a steamboat that capsized on the Mississippi River south of Memphis in 1925. An African-American river worker named Tom Lee dramatically rescued 32 people as they drifted helplessly in the current, including Harry Wiersema who had gone down 80 feet. It changed Harry’s whole life. Just two weeks after the event he married Jean’s mother Ethyl.

One of the homes Jean Weirheim designed in the cooperative, built in 1956, was recently up for sale. Not in the greatest shape, it had been owned by the same family for 45 years. It will most likely meet the fate of another residence of hers that was demolished and replaced with a McMansion. Although I’m hoping the house falls in the right hands of a person who appreciates and sees its potential. (UPDATE: Apparently it will be saved and restored. See comment below.) Fortunately Jean’s family home survives right as you first enter York Center on 14th Street.

John Wehrheim died unexpectedly at the age of 51 in September of 1962, leaving Jean a widowed mother of two children under the age of 10. In an interview from 1968, “the feminine architect” reflected that already having an established profession helped her cope with the loss. “I was not in a panic, as some widows probably are…I increased the business and gave more time to it.” The Chicago Tribune remarked that she “saw clients, installed wiring, cooked meals, handled the children, and mixed mortar.” An interesting observation that is still very much true today as many women juggle the responsibilities of balancing motherhood and their careers sometimes simultaneously.

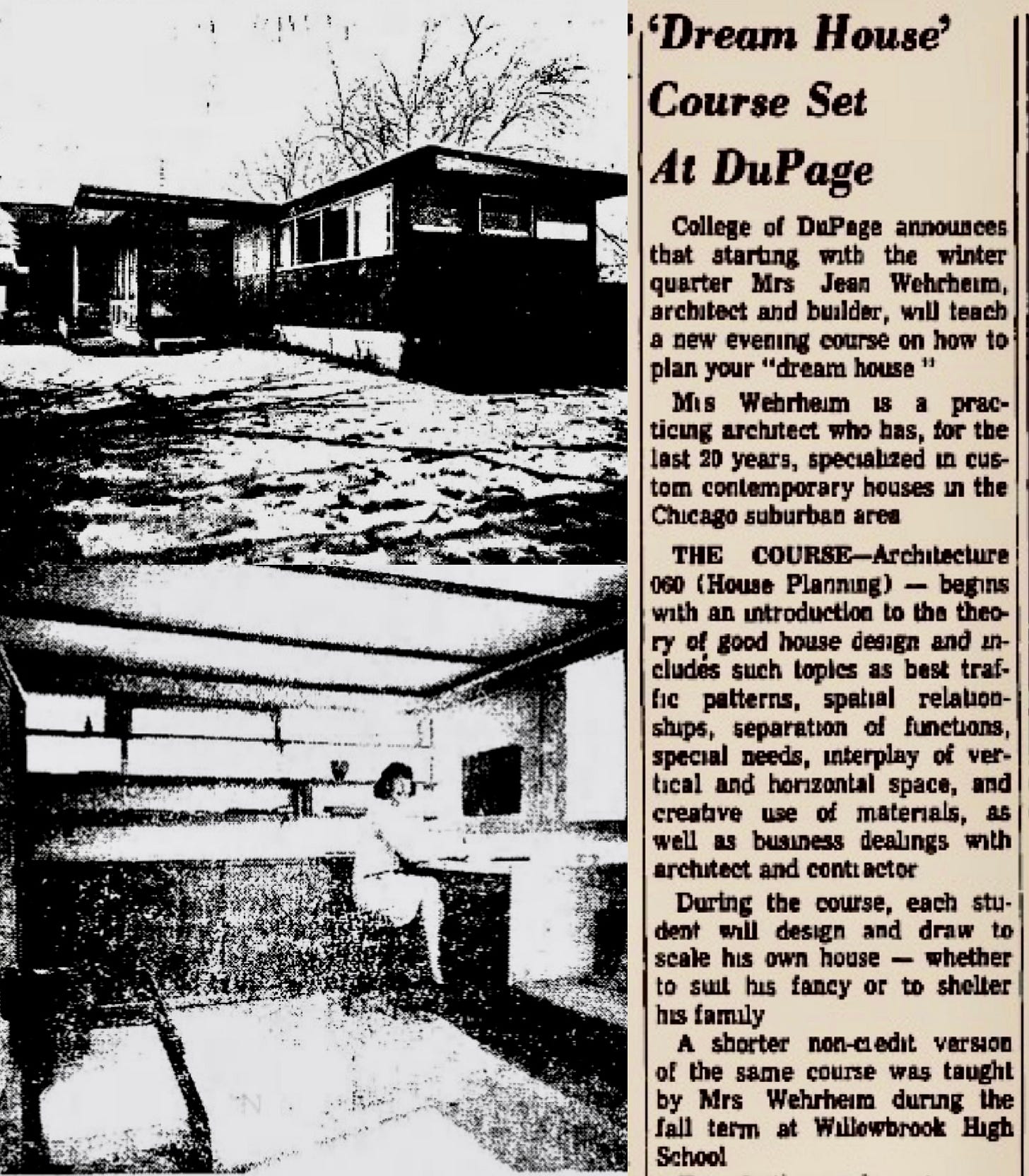

Jean’s workshop/office, attached to her single-story ranch-style residence, had its own slate-floored entry with a separate door leading to the main house. Eye-level windows installed on the south wall provided good daylight as she worked on projects like the Northlands Ski Resort in Crystal Falls, Michigan at her L-shaped counter top desk. A number of her residential projects were featured in the Chicago Tribune’s “Home of the Week” section in the 1960s and 70s. Beginning in 1968-69 Jean began teaching courses on architecture and house planning at Willowbrook High School, Lisle Township High School, and the College of DuPage. She focused on the solar orientation of the lot, interplay of space, and functional yet artistic architectural principles. While Jean joined the AIA in 1969, it seems like her career as a practicing independent architect was over by 1973-74, a few years before he death. Though prolific, designing over 150 houses during her career, Jean Wehrheim is virtually unknown today. Probably because she died young. In honor of Women’s History Month, I thought it was appropriate to to recognize this pioneering modernist architect; a role model for a generation of women hoping to practice architecture in a male-dominated profession.

Sources:

Crain’s Chicago Business

Landmarks Illinois

Lombard Historical Society

Modern in the Middle by Susan S. Benjamin & Michelangelo Sabatino

Newspaper Archive

What an interesting woman! Did you know Jean designed some dome residences in Lombard towards the end of her life? (As you might suspect, they are gone now but were on Luther Ave in Lombard.)

https://archive.org/details/messenger1974123112roye/page/n201/mode/2up

I would like to thank you for sharing my mom's life's story she had a heart of gold filled with love for everyone see met may God watch over her and keep her safe