One thing that has always stood out to me about the modernist architecture of Harry Weese is that he did not follow the trends of the day. In my personal opinion, his work is truly timeless. Not only is it original, but it also covered a wide range of projects including transit systems, infill townhouses, churches, and office towers. In the 1960s he was ahead of his time by saving and restoring historic structures like Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium (he offered his services free of charge). Or repurposing them, like the Fulton House, a former cold storage warehouse and the oldest surviving building on the Chicago River, which is now condominiums. As an investor he predicted the resurgence of Chicago’s South Loop when he bought and converted crumbling industrial buildings into lofts on what is now Printer’s Row in the 1970s. He was instrumental in saving Chicago's old elevated commuter‐train tracks from demolition. But what really fascinates me about Weese, who designed almost a thousand buildings during his long career, is the number of homes he produced not only for himself but for various family members. He talked about his early interest in residential work during an interview with Betty J. Blum in 1988: “That’s the only thing an architect can do when he starts out, because no one (except family) will trust him with anything bigger than that.”

In 1936, when he was only 21 years old (and two years before he graduated from MIT with a degree in architecture), Harry worked on his first official residential project. He designed and built the first of three cottages on the south shore of Glen Lake, Michigan, where his family still spends their summers. It became known as Shack Tamarack because it was constructed using locally-sourced Tamarack logs, with the longest log measuring 60 feet. The second cottage, built between 1938-39, was used by his parents. The glass home has simple, clean lines. While the interior walls are covered in tongue-and-groove black cherry wood. There are room-dividing sliding doors, which would become something of a trademark for the architect in his later residential designs. Both of these cottages are available as vacation rentals. Weese also designed a neighboring cottage that was built around the same time for Richard Pritchard, who was based in Highland Park, Illinois. I believe this home still exists.

Five years after completing his first official residential project in Michigan, Harry, along with his then partner (and future brother-in-law) Ben Baldwin, designed a passive solar home for his widowed aunt, Rosanna Weese Hall. She lived in the house with her two sons, William and Joe. Neighbors referred to it as the “airplane house” because of its dramatic tilted roof. Even eighty plus years later, the residence still stands out as an avant-garde design. Next door, Weese and Baldwin also designed a home for Harry’s other aunt. The following year a house was completed for his uncle, Robert P. Weese, in Barrington. Unlike the aunts’ homes in Evanston that are still standing (the “airplane house” was for sale five years ago while the other one is now altered), it seems like the uncle’s residence is no longer with us.

Speaking of Barrington, Harry Weese’s parents had a country retreat surrounded by apple orchards in the area since the 1920s. They built a prefabricated structure manufactured by the Aladdin Company, based in Bay City, Michigan, that sold more than 75,000 mail-order pre-cut “kit” homes from 1906 and 1981. Then, at the age of 25, Harry transformed it into what was known as the “Red House” in 1940 as a tribute to his architectural hero, Alvar Aalto. The year before, he attended lectures by Aalto at both MIT and Cranbrook. Although Harry first visited Sweden in 1937, where he was initially exposed to Aalto and the functionalism of Scandinavian architecture. The influence of Aalto, as well as Swedish architects like Gunnar Asplund and Sven Markelius, is even apparent in Harry’s later work, such as the now-threatened Oak Park Village Hall. Later, Harry’s parents retired with his brother Ben to the “Red House.” Unfortunately, this modernist home was demolished in 1983.

Harry Weese lived in several residences that he designed himself for his wife, Kitty, and three daughters: Shirley, Marcia, and Kate. These residences were located around the Barrington area, beginning with the “Water Tower House” in 1948. Named after the elevated water tank that loomed in the background, the weekend retreat was created at a time when Barrington was still a picturesque historic town, surrounded by open prairie, rather than the McMansion suburban hellhole it has become today. The small dwelling had a movable kitchen that pivoted on one side, and when fully open, it became a complete kitchen. I’ve always been intrigued to find out whether this home still exists. I have some theories, and I hope to one day solve the puzzle.

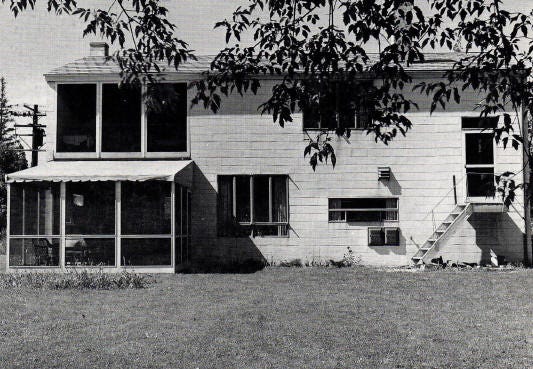

What followed the “Water Tower House” was a period of experimentation with lift slab construction for the rapidly growing small house industry. It’s no surprise that Weese responded to the post-WWII housing crisis with this daring design. Lightweight foam concrete was pumped into wooden forms, with openings left for doors and windows, to create the “Yellow House” four years after his first weekend retreat. The house was raised in only two days. The textured precast concrete walls were painted yellow, and an article “Precast Panel Walls for Small Houses" was published in Engineering News-Record in 1953.

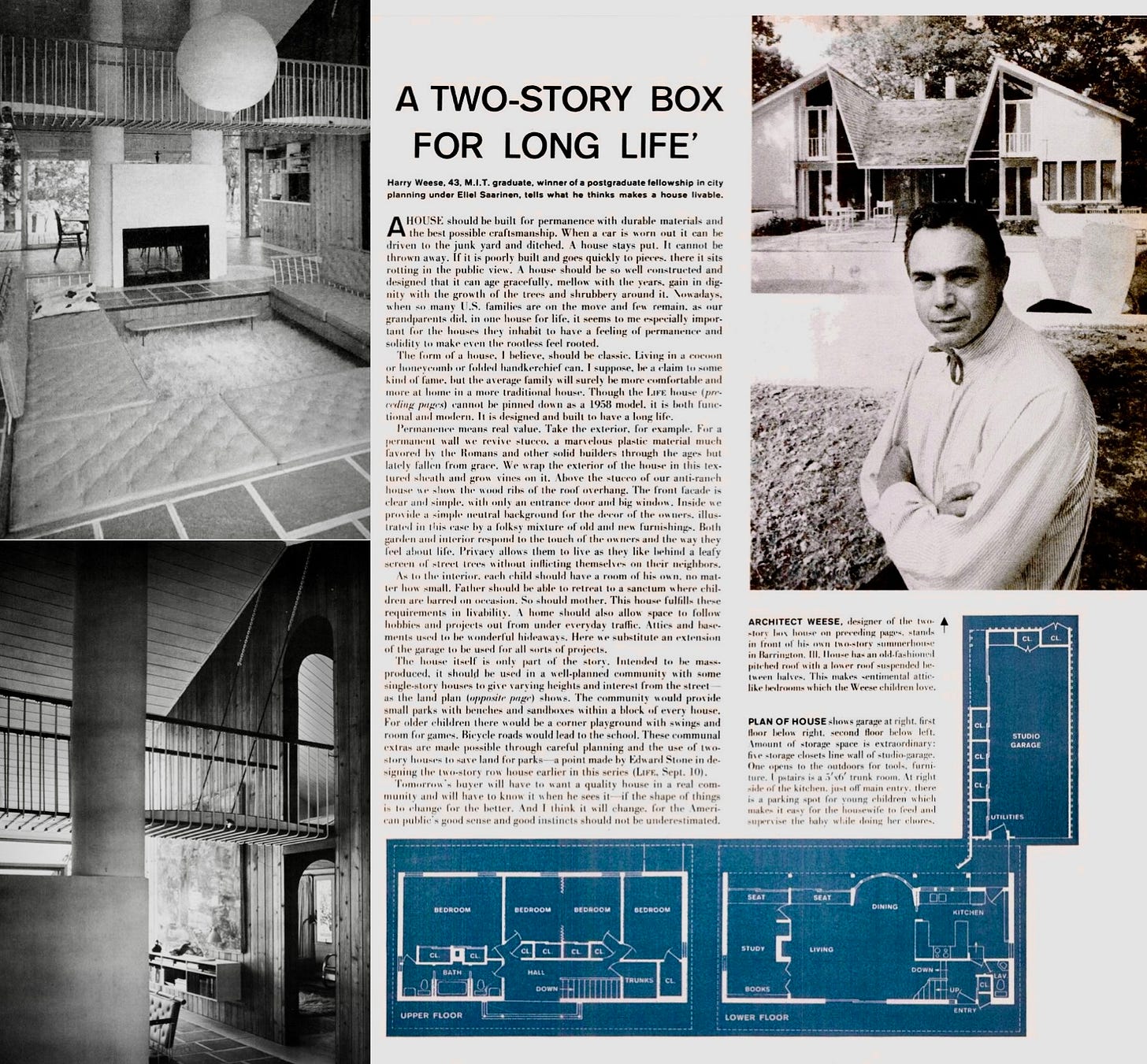

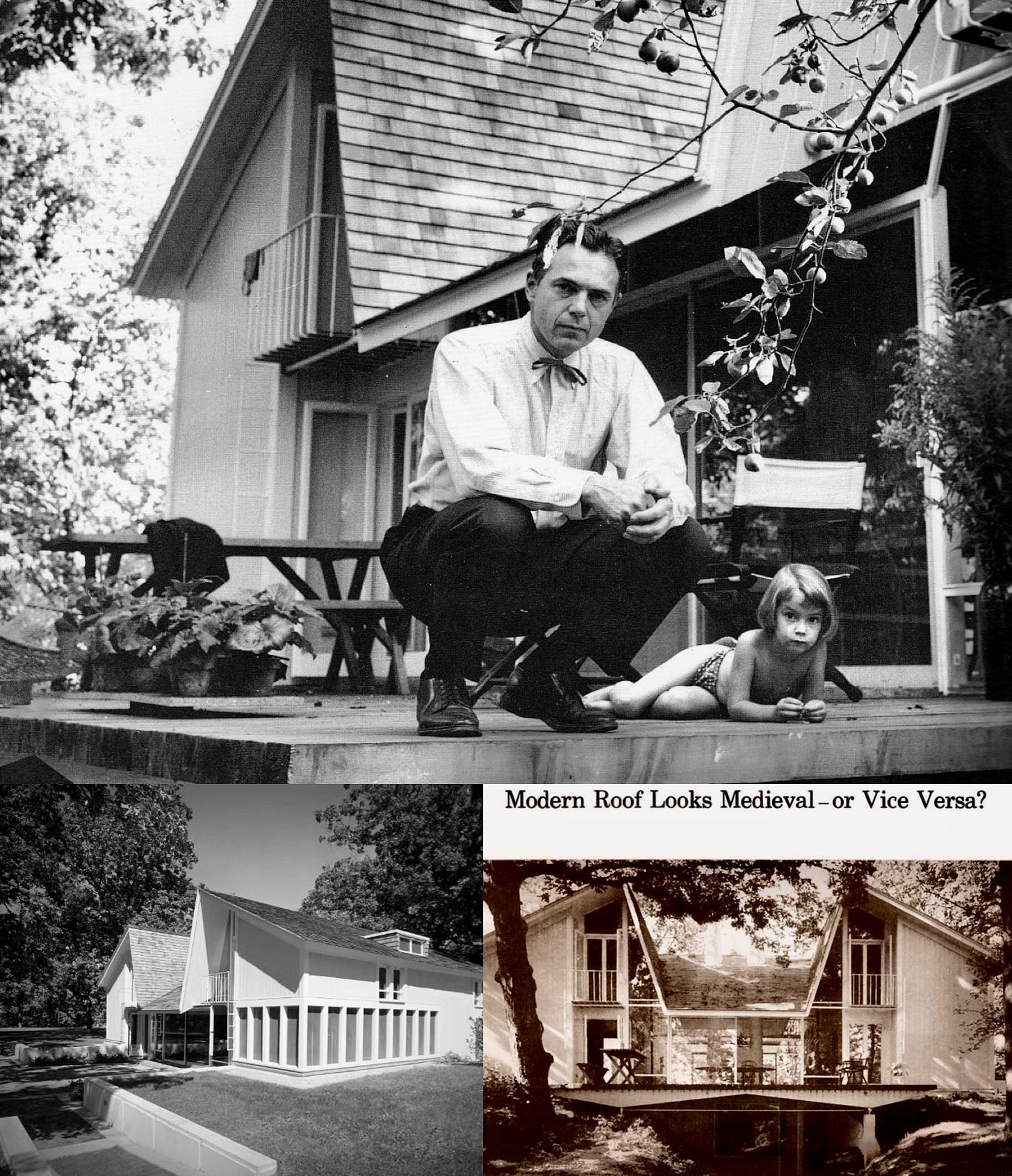

Harry’s most celebrated family residence, known as “The Studio,” was completed shortly after his career took off in the 1950s. The five-acre hillside retreat was built in 1957 on his father's land overlooking Keene Lake in what is now Barrington Hills. It was featured in LIFE magazine as part of a housing series and also in Architectural Record’s “Houses of 1960.” Harry’s friend from his Cranbrook days, Eero Saarinen, visited the Weese family in Barrington. Jody Kingrey and Kitty Baldwin Weese recalled Eero and Harry doing somersaults down the hill, flying over the grass. Bored and looking for something to do after it snowed, they used a Barwa chair as a sled and it broke up into many pieces.

The whimsical and cozy design, inspired by vernacular farmhouses in Alabama (the home state of Kitty Baldwin Weese), featured a central hall flanked by asymmetrical twin gables affectionately referred to as “cat ears.” The walls were covered in tongue-and-groove cedar cladding, an element which was a recurring theme in Harry’s residential projects, dating back to his cottage in Michigan. The sense of playfulness continued with the swaying seventeen-foot suspension bridge that connected the attic-like bedrooms located beneath each gable. Other unique features included a conversation pit, double-sided fireplace, and ladders that descended from each bedroom balcony to the stone terrace and outdoor swimming pool. In creating this family home for his wife and three daughters, Harry drew inspiration from Scandinavian modernist architecture while remaining true to his individualist spirit. “The Studio” is now on its own second owner since the property was sold by the Weese daughters in 1994, and has reportedly been restored.

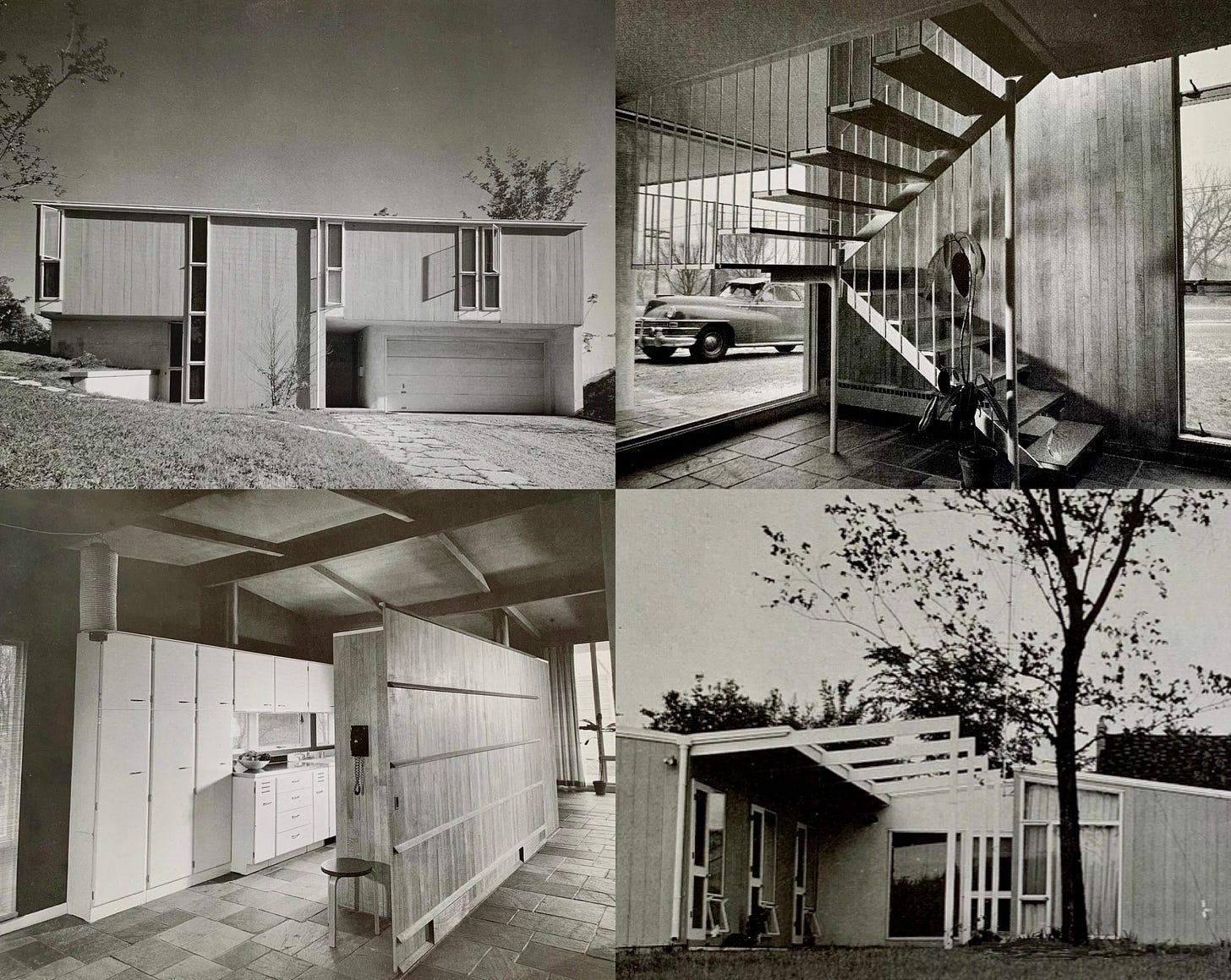

It’s no surprise that he was responsible for yet another family home in Barrington. In 1952, he built a year-round house for his sister Jane and her husband, Dr. Bill Welch (the brother of the Weese’s family physician). They resided there with their three children: Betsy, Steve, and David. It also had a doctor’s office with waiting rooms. Located on a hillside site on the appropriately named Hillside Drive, the doctor’s working spaces were on the ground level, with living areas above, including a galley kitchen and bedrooms that opened onto terraces. The exterior is covered in vertical grooved boards that are painted in a driftwood grey, which is believed to be the original color. The design with separate living and work spaces was ahead of its time by 70 years with today’s trend for remote work.

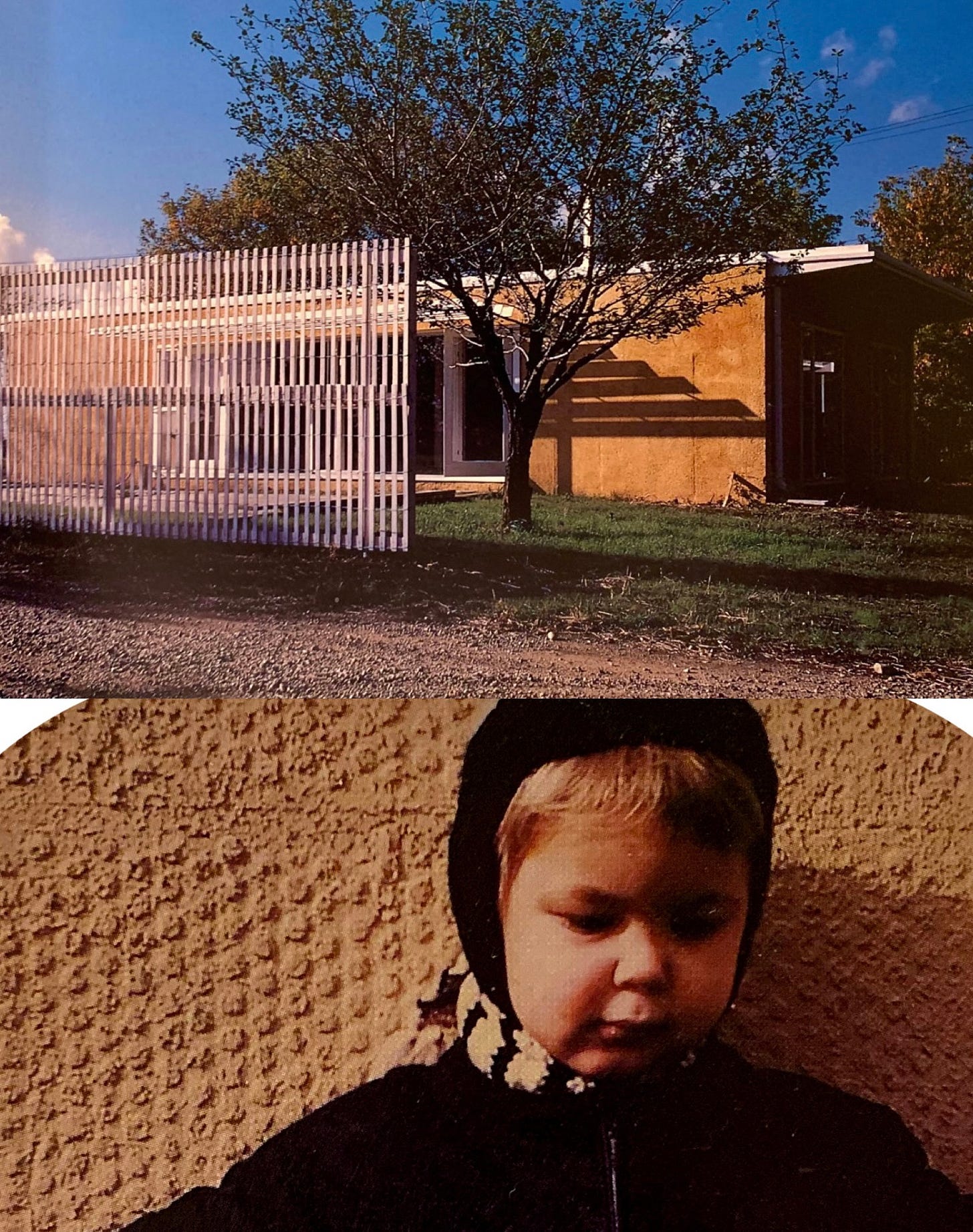

Harry’s other sister, Suzanne, with her then-husband, Robert Drucker, also got a custom-designed house. Now an officially recognized local landmark, the board-and-batten design, which was built in 1952-54, is located in Wilmette’s Indian Hill Estates. The subdivision was partially developed by her father-in-law, Henry W. Drucker, a real estate attorney who created a 170-acre area of fashionable Tudor and Colonial Revival homes on curving roads in the 1920s and 30s. Throughout the design process, the siblings worked together to create a functional and comfortable home. She was concerned about the feelings of her traditionally-minded neighbors, but found out they were fine with the modern house, which took over two years to complete due to contractor issues (they lived nearby with Henry and Mary Drucker). Even thirty years later, Harry was still advising his family on the maintenance of the future landmark.

Quietly secluded from the street by slatted screens and mature trees, the simple cubic house seamlessly combines Harry’s main influences of International Style, Scandinavian, and Midwestern architecture. The L-shaped design with a flat roof and carport features numerous glass windows that face the backyard for southern exposure, allowing ample natural light to enter the home. The interior has an open floor plan with walls that do not reach the ceiling, and accordion doors that can be closed to create privacy. The home featured a doubled-sided fireplace, similar to the one found in “The Studio” in Barrington. Keeping it in the family, Ben Weese, a notable architect in his own right, designed an addition in 1963 for the growing family of 5 kids that was compatible with the style, scale, and materials of the original home.

Over seventy years after it was first envisioned by Harry Weese, this unique modernist work is still owned by the Drucker family. Last month, Suzanne Weese Drucker Frank died at the age of 100. She spent her last summer, like all the years before, at her parents’ rustic cabin on Glen Lake in Michigan. The one designed by her brother 85 years ago. Sue took one final swim in the water that had been long-cherished by the Weese family. Before her death, Sue ensured the protection of her residence in Wilmette for future generations by having it listed on the National Register and locally designated as a landmark.

As noted in the book Modern in the Middle, “Harry Weese’s early houses were always modern. Unlike many architects who evolved from designing in historical styles to receive commissions (Frank Lloyd Wright, George Fred Keck, and even Mies van der Rohe come to mind), Weese never compromised his commitment to modernism by deferring to popular taste.” You can see how he accomplished exactly that, specifically by taking a humanist approach, when creating the homes for himself and his family members.

I grew up in Evanston, with my parents Robert Weese Harker, and Jean Harker and sister lived. My grandmother, Mildred Weese Harker (Granny), and her sister, Aunt Rosie (as we knew her), had the two houses built by Harry Weese. I have fond memories of staying at my grandmother’s house (great Thanksgiving memories) and visiting Aunt Rosie’s, where she always had fun candy and baked delicious cookies. I also cherish memories of visiting Harry Weese’s designed house in Barrington, especially the suspension bridge across the sunken living room - a marvel for a 10-year-old like me! My father maintained a close relationship with Harry Weese until his passing in 1987. I’m Bob Harker. Peace.

Is the water tower house located just to the south of the Bill and Jane Welch House? Satellite images of 715 S Hough St look like the house, courtyard, and covered car port to me! The orientation, relation to the water tower, and chimeny location too. It does look like they added a sloped roof/cupola and a separate garage.