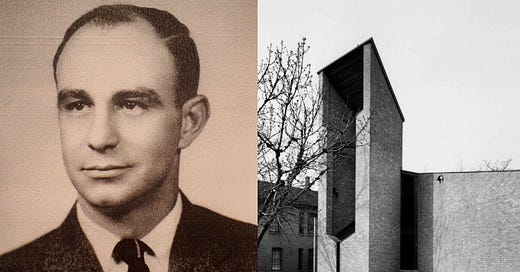

Edward Dart's Emmanuel Presbyterian Church (1965-2007)

2022 marks the 100th anniversary of Edward Dart’s birth. One of my favorite modern architects, I believe Dart’s work deserves more love and attention, which I hope to do every month on this substack. During his days at Yale, Edward “Ned” Dart was greatly influenced by visiting professors like Marcel Breuer, Richard Neutra, Louis Kahn, Eero Saarinen, and Paul Schweikher. The latter created such an impact on the young “Ned” that he moved to the Chicago area to briefly work for him. Even though he practiced architecture for only 25 years, Dart was an innovative architect who left a lasting mark on Chicagoland’s building environment. Best known for Chicago’s Water Tower Place (a project so stressful that it most likely led to his untimely death of an aneurysm at the age of 53), Dart designed at least 52 custom homes around the Chicagoland area but he was also known for his small but interesting churches.

Edward Dart became a leading modernist church designer in the 1950s and 60s. He created 26 new buildings for small, but growing congregations across all parts of the city and surrounding suburbs from his first church commission for St. Michael’s Episcopal Church (1952) in his hometown of Barrington to what is considered his greatest building, St. Procopius Abbey (1970) in Lisle. Like any good architect, Dart was known for incorporating a building to its site, using natural materials, and creating light-filled, minimalist interior spaces.

Unfortunately we have lost at least eight of his buildings over the last fifteen years: the Barry Crown House (1965) in Glencoe, the Jel Sert Company’s plant and offices (1961) in Bellwood, and two churches in Barrington and West Chicago. All were huge losses to preserving Dart’s legacy but in my opinion, one of the greatest tragedies was the 2007 demolition of Emmanuel Presbyterian Church in Chicago’s Pilsen.

Featured on the cover of Inland Architect in 1975, the same year of Dart’s death, the church was built in 1965 near the northwest corner of 19th and Racine - 1850 South Racine Avenue to be exact - and today is still an empty lot. Many city neighborhoods are not uniform in appearance; yet there is a positive in this as different architectural styles situated side by side help make urban areas visually interesting. When it was originally constructed, the modernist church stood out from its historic 19th century neighbors, creating an interesting juxtaposition. Architectural critic Blair Kamin described Dart’s church as “a powerful urban presence…despite its modest size and lack of traditional ornament.”

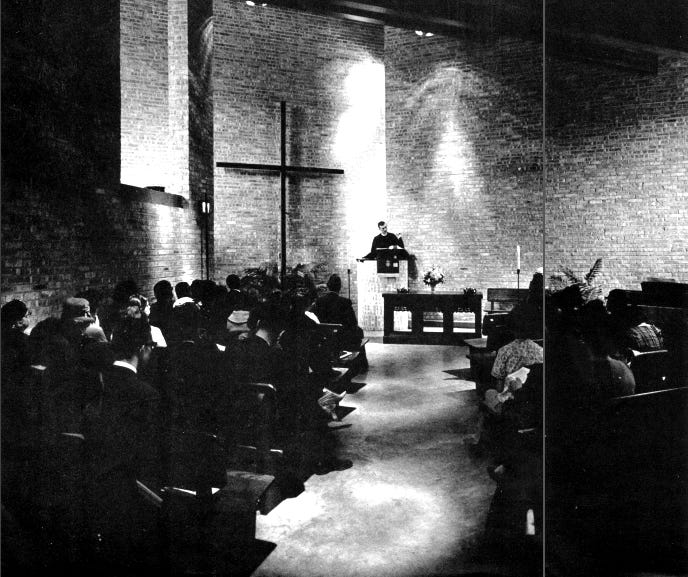

Featured in an article in Architectural Forum in June of 1966, Dart’s church is described as “using blade-like wall planes set at irregular angles” that “differs in form from all that is around it,” but yet fits “snugly into its allotted space.” Although the church’s “perplexing forms” differ from the “endless grid around it,” the design offers a bridge between older white residents and immigrants, a welcoming and protective presence to the new minority groups, mostly Mexicans, who have moved to this neighborhood in recent years. The recipient of an AIA award in 1967, the church was clad inside and out with Chicago Common brick, one of Dart’s favorite materials, while the exterior’s angled shed roof line drew one’s attention to the dominant belfry/bell tower. There are no historical references here, just abstract geometry. The entrance is tucked away.

The building was set back from the sidewalk to take advantage of the existing lower grade, therefore creating a small, landscaped garden space. It helped provide relief at what the time was a very congested neighborhood. One could take in the views of this area from full-story height windows at the basement level, where multi-purpose rooms, library, and kitchen were located. Another interesting aspect of the nearly 5000 sq ft building was that one entered the sanctuary by means of a ramp to the back of the church. The American Institute of Architects’ Guide to Chicago recalled that “the thin, angular brick wall planes appear idiosyncratic until you step inside to see how their careful placement catches the light. Inspired rather than hamstrung by the small budget, [Dart] made morning light the most powerful architectural element, casting it across the angled chancel wall to create a sense of shelter and spirituality.”

In the book Public Religion and Urban Transformation: Faith in the City, Dart’s sanctuary is described as “a complex and free-flowing design, intended by the architect to convey both a welcoming and protective shelter.” There were no distractions like stained glass or statuary as one would find in a historic Catholic church, instead one found simple, honest materials of brick and wood with natural light flooding the windowless walls, creating an ethereal feeling. Modernism can sometimes be seen as cold and sterile (Mies van der Rohe immediately comes to mind) but Dart’s spaces tend to feel more human-like. Light comes from hidden sources. Even though there is a sense of heaviness from the brick, warmth and togetherness is also achieved in the small, enclosed space. Because the form of the nave was semi-circular and the sanctuary fan-shaped with converging side walls, the number of pews were kept to a minimum. Congregants could just focus on worship and private meditation.

Dart believed church designs should be seen as reflections of social justice. Not only was the church architecturally significant, but it also played an important role in the local Latino community during the 1960s and 70s. Reverend Jose “Joe” Burgos sought to improve immigrants’ general living conditions and change their poor self-image at the time. Money was raised to provide college education and job training for youth, Burgos also helped to organize community organizations to defend residents from a number of urban renewal projects. Church members wrote letters to senators supporting economic opportunities for all. Burgos also played an integral role in ending the five-day occupation of the McCormick Theological Seminary by the Young Lords Organization (YLO) who sought funding for a legal office, a health clinic, and low-income housing in Lincoln Park. He believed in building coalitions between Latino pastors and radical activists.

But when Reverend Rolando Cuellar took over the congregation in 1983, it was the beginning of the end for the building. Membership grew to such an extent during the 1990s, the hundreds of people who would regularly attend Sundays services could not all fit into the sanctuary (it had originally been built for a maximum of 125 persons). The church actively started looking for a new building, and eventually left this vibrant city neighborhood for a suburban location in nearby Cicero.

After sitting empty for years, the structure was quickly torn down in August of 2007 by new owner Patrick Heneghan of the Heneghan Wrecking Company. There was little that preservation advocacy groups like Landmarks Illinois could do at the time. Its demolition can partially be blamed on its exclusion from the sprawling 1995 Chicago Historic Resources Survey (CHRS), which documented potential landmarks across the city but stops abruptly in 1940. Now 15 years after its demolition, postwar 1960s buildings like Dart’s church are still not included in the CHRS. That means they are not covered by Chicago’s demolition delay ordinance, which requires city officials to put a hold up to 90 days on demolition permits for significant buildings rated in the color-coded survey. In 2022 a building constructed over the last 80 plus years can be torn down, no questions asked.

Although it is sad Dart’s Pilsen Church was torn down, I don’t want to be all doom and gloom as there have been some Dart success stories over the years, like the Louis Ancel House in Glencoe and the Richard and Charlotte Henrich House in Barrington, which I hope to share in future articles. Please stay tuned for more Edward Dart buildings as we remember him on the 100th anniversary of his birth!