Right next to the Des Plaines River on Lake Street in Maywood is a McDonald’s. You might not think twice about something so ubiquitous, but it is worth a stop. Why, you might ask? Well, if you appreciate history like I do, there is a memorial, dedicated in December of 2000, in the parking lot that recognizes what once stood here. The “10 Mile House” was a stagecoach rest stop that was secretly part of the Underground Railroad. Runaway slaves, who usually traveled at night, would stay in the building’s hidden rooms during the day, while families with small children or babies would conceal themselves along the riverbank. Its name originated from the stagecoach stop being 10 miles, equivalent to a day’s journey, from the city of Chicago. Nobody knows when the inn was originally constructed but it was demolished in 1927. On the plaque memorializing the site is a quote from Harriet Tubman:

"If ya' wanna be free, keep a goin'

If ya' tired, keep a goin'

If ya' scared, keep a goin'

If ya hungry, keep a goin'

If ya' wanna taste freedom, keep a goin'"

The village of Maywood has been multi-racial since its earliest days, with many African-American residents working as tradesmen and laborers in nearby Chicago. It all started with Iva Hurst, who worked as a cook at the Palmer House in the 1880s. He saw a real estate advertisement for the new “railroad suburb” of Maywood. If a potential buyer wanted to buy land, they had to attend the town’s Fourth of July picnic with hopes that one of the rockets that shot into the air had their number on it. Iva wasn’t so lucky, but that didn’t stop him from becoming a pioneer of what is now remembered as Maywood’s Ebonyville.

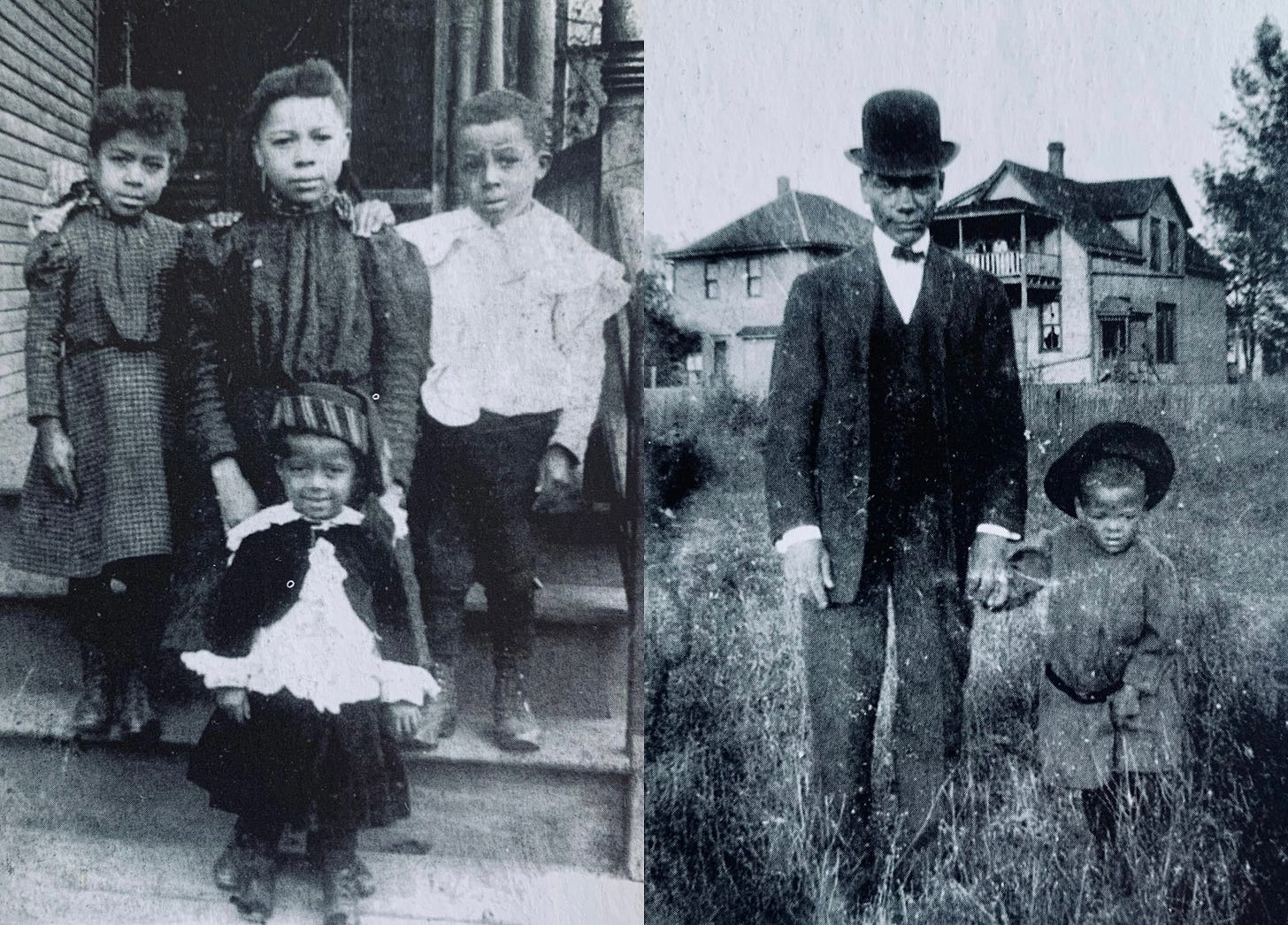

Even without a rocket number, Iva and his wife, Amanda, purchased two lots and built a house for themselves at what is now 417 South Thirteenth Avenue in 1887. Other Black and Jewish families followed them, such as Albert Stump whose son and namesake would become a Tuskegee airman. Unlike Chicago and many surrounding suburbs, African Americans were allowed to purchase property in Maywood. But there were still restrictive covenant real estate policies in place. They could not live outside a specifically outlined “colored neighborhood,” which was located between Ninth Avenue on the east and Fourteenth Avenue on the west. The Hursts would have six children, all delivered by their neighbor, a Jewish midwife named Bella Barsky.

Their grandson, Sidney, was still living in the family home when he died at the age of 97 in 2022. Sidney’s mother, Ethel, had a connection to another pioneering Black family in neighboring Oak Park. Her parents, John and Louise Shannon, had lived in that village since the 1880s, eventually settling at 838 Belleforte, close to other Black people who owned parcels of land. Originally from Kentucky, John was the son of slaves and was known as a blues guitarist who played in taverns around Harlem, which soon changed its name to Forest Park. Although neighbor, Dr. Clarence “Ed” Hemingway, was their doctor, and the family had a number of white friends, Louise always said to her children: “You’re the only fly in a bottle of milk.”

Maywood, like Oak Park, is full of history. Musician John Prine, architect Walter Burley Griffin, comedian Judy Tenuta, poet Carl Sandburg, and actor Dennis Franz all once lived here. But probably the two best-known former residents of Maywood are Dr. Percy Julian and Chairman Fred Hampton.

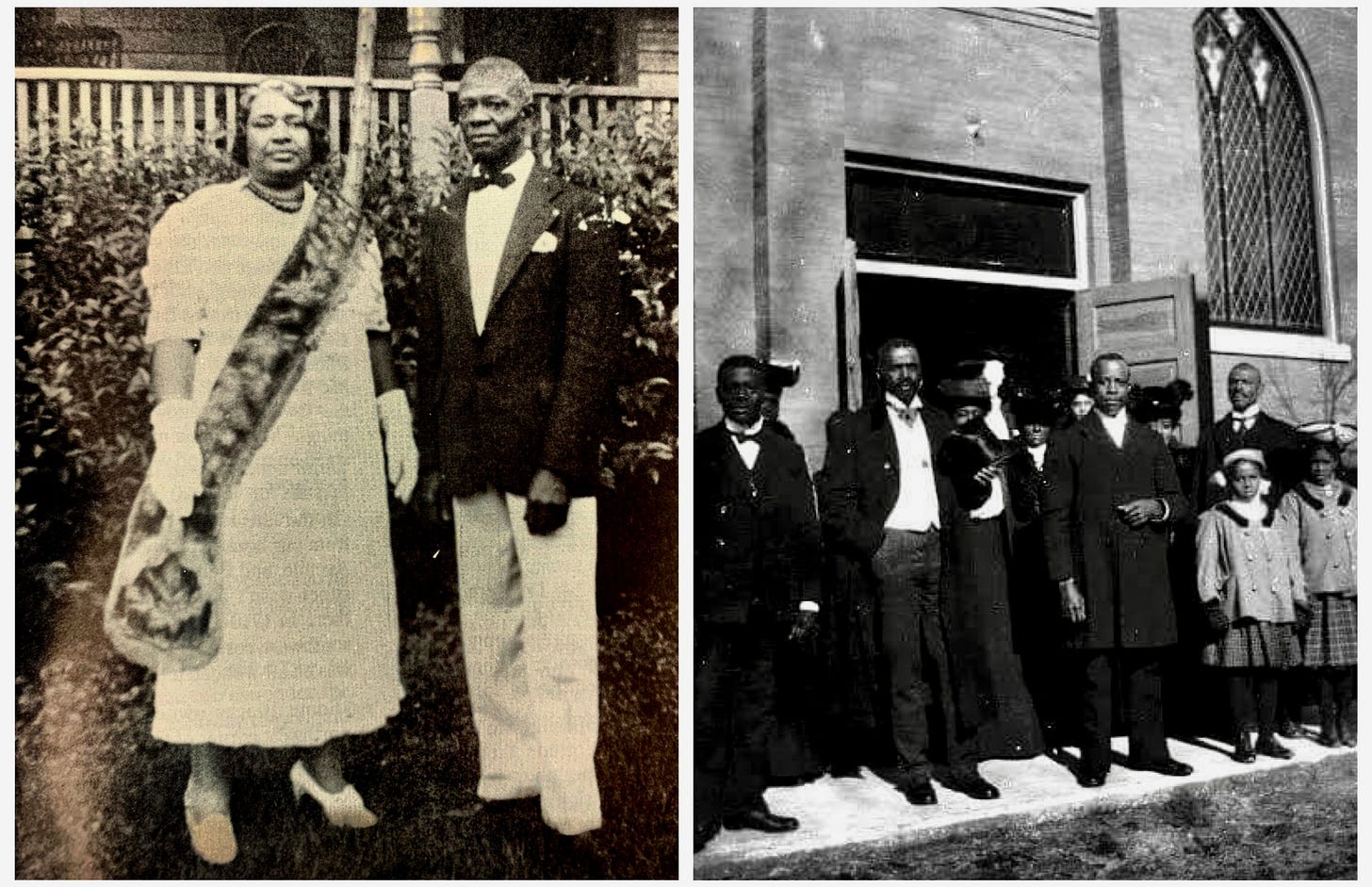

Dr. Percy Julian, a world-renowned chemist, synthesized stigmasterol from soybean oil, which ultimately led to the development of the hormones used in the birth control pill. Not only was he one of the first African-Americans to graduate with a doctorate in chemistry, but Julian also headed his own research laboratories in Franklin Park and received more than 130 chemical patents. Percy’s wife, Anna, became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in sociology. The family resided in a Chicago-style bungalow at 152 S. Fourteenth Avenue between 1935 and 1950, where he was active in the local branch of the NAACP. The Julians then moved to Oak Park.

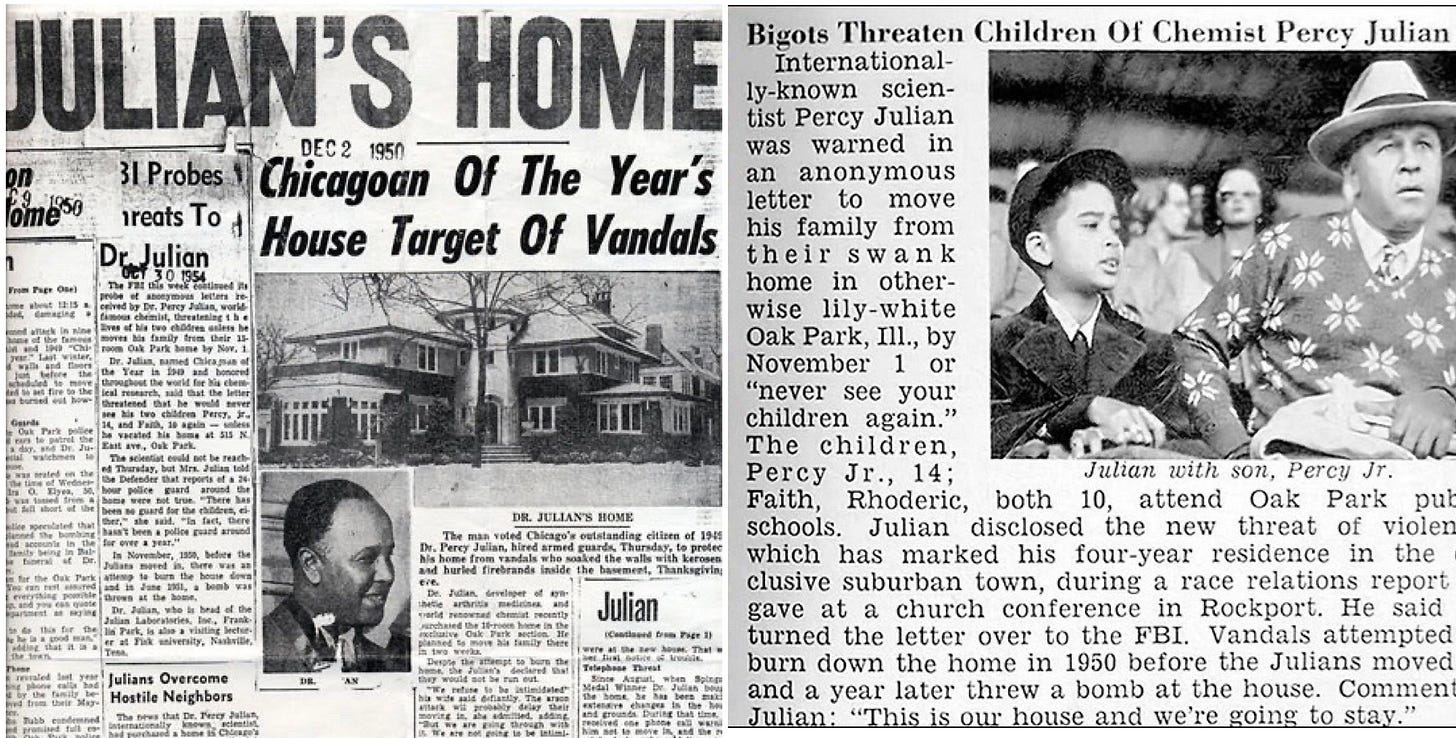

They purchased a Prairie-influenced Tudor Revival residence on East Avenue that had been designed by architect Thornton Herr in 1908 in one of Oak Park’s most exclusive neighborhoods. On Thanksgiving Day 1950 their new home was firebombed, even though the family had not moved in yet. Arsonists had broken into the building, and gasoline was splashed on the floors and walls of the home’s fifteen rooms. The vandals failed to light it, but a kerosene torch was tossed through a window. Fortunately, firefighters saved the home from further destruction.

But the terror didn’t stop. The family soon received a number of anonymous threatening letters. Percy and Anna would never see their children again. Percy’s own life was at stake. The FBI began an investigation while the Julians hired private guards as they couldn’t depend on local police protection. Percy Julian himself, along with his 14-year-old son, Percy Jr., would stand under a tree with a shotgun. Not even a year after the Thanksgiving bombing, a stick of dynamite was thrown at the home. It scared their 10-year-old daughter, Faith, so much that she had to sleep with her parents. It was a smell that she would never forget. Percy Julian didn’t give up hope: “This is our house and we’re going to stay.”

And stay they did. This past month Rep. Danny K. Davis announced he will be introducing legislation that will designate Percy Julian’s home as a national historic site. Faith Julian, who will turn 80 years old in 2024, still lives there and has struggled with being able to afford the old house’s upkeep and high taxes. She would like to see it turned into a learning center. The home is already a contributing structure in the Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Historical District, but let’s hope it will soon be individually landmarked for its important historical connections and preserved for future generations. Today Oak Park has a middle school and life-size bust honoring Percy Julian.

Turning back to Maywood, the ancestors of Fred Hampton’s parents, Iberia and Francis, farmed the land for generations in their native Louisiana, first as slaves and then as sharecroppers. In the 1930s, Francis moved to the Chicago area and found a job at the Corn Products Refining Company in Argo, now Summit, where his third child, Fred, was born in 1948. Iberia would also work there, starting in 1956, but in the meantime stayed home with her kids and sometimes babysat one of their neighbors, Emmett Till. When Fred was 10 years old, the Hampton family purchased a two-flat at 804 South Seventeenth Avenue in Maywood, when the suburb was about one-quarter black. Fred’s childhood home officially became a landmark in 2022.

Fred’s activism starting early. As a student at Proviso East High School, he spoke out against inequality and racism, demanding more black teachers be hired and organizing a walkout in support of a black homecoming queen. A year after his graduation, the principal asked Fred to return to the school for a three-day workshop to help ease racial tensions among Latino, white, and black students and community members. Local historian and former Proviso East teacher, Doug Deuchler, clearly remembers the day of Fred’s murder on December 4th 1969. Some of his colleagues said Fred should have been shot earlier. Students failed to show up for class. The school refused to hold a memorial, causing mobs of young people to smash windows along Maywood’s main shopping district. Proviso shut down for the rest of the year on “Christmas break.”

While a swimming pool doesn’t sound like a big deal to most of us, 18-year-old Fred Hampton was determined that Maywood have its own non-segregated swimming pool, community recreation center, and independent park district. Blacks were not allowed at nearby pools in Melrose Park and Bellwood, which were for whites only. Fred organized car pools and bus trips to Brookfield and Lyons so local kids could swim. In May of 1970 Maywood’s newly constructed municipal swimming pool was renamed in Fred’s memory, although many white people in the meeting’s audience of 300 yelled obscenities. One of Fred’s Proviso classmates, John Prine, played at the pool’s opening and recalled that officials appeased Maywood’s rioters by giving them a swimming pool. A bust outside the Fred Hampton Family Aquatic Center was dedicated in 2006. According to Fred’s brother Bill in 2013: “It’s the people’s pool-what Fred always wanted it to be.”

Sources:

The Assassination of Fred Hampton by Jeffrey Haas

Images of America: Maywood by Douglas Deuchler

Village Free Press

Historical Society of Oak Park & River Forest

Thank you for the interesting history of Maywood and Oak Park. Progress regarding racism thankfully has been made since then but more is needed. Knowing past history is certainly part of the progress.

Thank you for sharing this important and moving story. I’m looking forward to more. So much tragedy, will, and strength at the same time.